This past weekend, I offered Baptist ecumenical reflections on Pope Francis’s most recent encyclical “On Fraternity and Social Friendship” (Fratelli Tutti) on the program of the Hearth for the Human Family conference sponsored by the Focolare Forum for Dialogue and Culture, a Catholic lay-led ecumenical organization.

My task was to address three questions:

- Who are you, what Christian tradition you are a part of, and how you are involved in the work of Christian unity?

- What do you think are key challenges to Christian unity in North American culture?

- In the light of your tradition and the challenges to Christian unity you identified, what resonated with you as you read Fratelli Tutti?

Here’s what I said:

On intra-denominational division

I’m a Baptist by upbringing, baptism, ordination and education (with the exception of a year studying patristics at The Catholic University of America). The specific expression of the Baptist tradition with which I identify is the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, founded in 1991 in the wake of intra-denominational division in the Southern Baptist Convention.

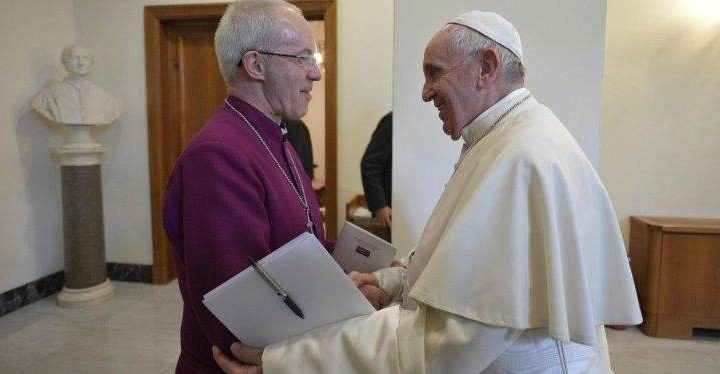

Despite the origins of my ecclesial identity in Baptist division, a vocation within my vocation as a Baptist theological educator has come to be ecumenical engagement. This has been principally through the Christian world communion of the Baptist World Alliance, which I’ve represented on the plenary Commission on Faith and Order of the World Council of Churches and in international ecumenical dialogues with the Anglican communion, the Catholic church, and “pre-conversations” with the Eastern Orthodox churches. I’m currently serving as co-secretary of Phase III of the international Baptist-Catholic dialogue.

“The real divisions in Christianity are not so much between denominations as within them.”

I mentioned intra-denominational division in the SBC. Ecumenists have been observing for a couple of decades now that the real divisions in Christianity are not so much between denominations as within them. I think that continues to be true.

There’s a sense in which that occasions some new sorts of ecumenical alliances. Conservative Methodists may discover they have more common cause with conservatives in other denominations than with progressives in their own communion, and they may live into those commonalities in concrete ways. Progressive Presbyterians may discover they have more common cause with progressives in other denominations than with conservatives in their own communion, and they may live into those commonalities in concrete ways, too.

But while these alliances may seem to be expressions of unity, they greatly exacerbate the problem of Christian division in North America. They foster the harmful notion that true Christian unity requires a common allegiance to a particular set of ideological commitments in the North American culture wars, and that Christian unity is impossible with baptized Christians on “the other side” of these conflicts.

Not only does this deepen Christian division; it keeps the church from fulfilling its larger participation in God’s mission that the quest for Christian unity serves. In the words of the World Council of Churches convergence text The Church: Towards a Common Vision: “Communion, whose source is the very life of the Holy Trinity, is both the gift by which the church lives and, at the same time, the gift that God calls the church to offer to a wounded and divided humanity in hope of reconciliation and healing.”

Theological anthropology

As a theologian, I note that these newer divisions in American Christianity are fundamentally disagreements over theological anthropology — our thinking about God’s creative intentions for humanity as the image of God. The old divisions over ecclesiology, doctrines related to the church, still persist, and progress in our pilgrimage toward the ecumenical future requires ongoing work on them.

“It’s anthropology that most sharply and bitterly divides American Christians at the moment: gender, sexuality, race, the political expression of civil order.”

But it’s anthropology that most sharply and bitterly divides American Christians at the moment: gender, sexuality, race, the political expression of civil order as a context for human relations. Divisions related to these issues are rooted in disagreements about theological anthropology. Who are we, as creatures in the image of God, in relation to one another?

As a theologian, I have a couple of observations about theological anthropology that inform my thinking about these recent divisions.

The first is that theological anthropology is the doctrine of Christian systematic theology that historically has been more shaped by the dialogue between the church and its cultural context than any other aspect of doctrine, and it’s a dialogue that stretches over long periods of time. I’m not saying theological anthropology simply acquiesces to cultural understandings of what it means to be human. Far from it! But ever since the Bible itself and the tension evident in the New Testament between Hebrew and Greco-Roman understandings of human identity, the church has had a long conversation with various expressions of its cultural context that has shaped in different times and places the way it answers the question, “What does it mean to be human?”

This leads to my second observation: These anthropological divisions are over the doctrine of Christian theology that is the least well-established in terms of historic ecumenical consensus. The doctrines of the Trinity and Christology were hammered out in ecumenical councils; anthropological questions like the nature of free will were addressed in regional synods in relation to controversies of a more local nature.

All this should make us reluctant to root our reasons for maintaining any current division in our sharp differences over anthropology. And yet, it also won’t do simply to agree to disagree over these matters of theological anthropology, for authentic Christian unity must be a unity in the truth, and the sharply diverging perspectives that Christians and their churches have on some of these matters are symptomatic of our lack of a unity in the truth.

The church in North America contests these things in the midst of a culture that wants people to decide their stance on these matters of anthropology right now, especially regarding gender and sexuality. In my judgment as a historical theologian, we haven’t yet had a sufficiently long conversation with our cultural contexts about some of these things to be able to declare our stances in ways that invite ecumenical convergence toward a unity in the truth.

But in the meantime, there are anthropological resources in the Scriptures and the Christian tradition that can help the church live more fully into its ecumenical mission of offering the gift of communion “to a wounded and divided humanity in hope of reconciliation and healing.”

Fratelli Tutti is a much-needed distillation of these resources and a timely fresh statement of their import for the challenges facing the North American Church. As such, it’s immensely helpful to Baptists and the whole church, as well as to Catholics.

Our wounded humanity

Fratelli Tutti is helpful in the way it describes and diagnoses our wounded and divided humanity. In this connection, I found especially noteworthy the frequent quotations from Francis’ previous encyclical on care for the environment, Laudato Si.

My first reading of Laudato Si was on the morning of its public release online on June 18, 2015. I was attending the General Assembly of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship in Dallas, devoted to the theme “Building Bridges,” with bridges crossing racial divides among the principal applications. We had just learned of the murder of nine African American members of Mother Emmanuel A.M.E Church in Charleston, S.C., by white supremacist Dylann Roof the previous evening.

I read quickly through Laudato Si over breakfast with that weighing on my mind, and I was struck by the applicability of its theological framework for ecological justice to the pursuit of racial justice. Its analysis of the human roots of the ecological crisis was nothing less than a theological anthropology. It was an account of God’s creation of humanity for relationship, for relationship with God, fellow humanity and the rest of the created order. It described how the sinful turn away from the other and toward the self lies at the heart of the modern alienated relationship between humanity and creation, with the violence that marks human relationships seen as an expression of this alienation.

“A distorted anthropology accounts for both violence toward creation and violence toward people.”

A distorted anthropology accounts for both violence toward creation and violence toward people. A restorative anthropological vision of the interconnectedness of humanity and of the whole of creation offers the hope of reconciliation and healing both for humanity and for the whole created order to which humanity belongs.

This relational theological anthropology is developed more fully in this new encyclical as a theology of human fraternity that answers to the aversion to the “other” that marks many expressions of contemporary American culture. The other who is other than us is inseparable from our identity as human. To be fully human is to be in relationship with people who aren’t like us. When we’re in relationship only with those who are like us, we are less than the fullness of the creation of humanity in the image of God.

Remembering our Baptist roots in persecution

As a Baptist theologian, I believe reflection on Fratelli Tutti can help Baptists live more fully into the best insights of our own tradition. The formative Baptist experience for much of the first century of Baptist existence was persecution as a religious minority.

In 17th century England, Baptists were the religious other and often the socio-economic other. Otherness, especially religious otherness, was perceived as a threat to the stable order of English society. Liturgical non-conformity — worship other than what the Book of Common Prayer prescribed — was an especially flagrant manifestation of otherness in a culture that valued conformity.

“In 17th century England, both Baptists and Catholics were persecuted religious others.”

I should add that this is an important shared experience of Baptists and Catholics. In 17th century England, both Baptists and Catholics were persecuted religious others. While the worst forms of persecution ceased with the 1689 Act of Toleration, it wasn’t until the mid-19th century that Baptists, Catholics and other nonconformists were admitted to the British universities and allowed to hold public office.

Thomas Helwys was co-founder of the first Baptist church of historical record in 1609 among English expatriates in Amsterdam. A couple of years later, he and a small group from that congregation returned to England, founded the first Baptist church on English soil, and soon encountered severe persecution. Helwys himself died in prison in 1616.

Before Helwys’ imprisonment, he had published the first English book to argue for religious liberty. In it he wrote, “Let them be heretics, Turks (that is, Muslims), Jews, or whatsoever, it appertains not to the earthly power to punish them in the least measure.” At a time when religious and ethnic others like Muslims and Jews weren’t that numerous in England, Helwys envisioned a society in which the free encounter of “others” with one another would be the norm.

Roger Williams, founder of the First Baptist Church in America in 1638, echoed Helwys when he introduced such a vision into the American experiment. Williams had established the colony that became Rhode Island in 1636 as a place where “Jews, Turks, Papists, Protestants, and pagans” would enjoy full liberty of conscience.

Martin Luther King

This is the tradition that formed the one Baptist whom Pope Francis mentions in Fratelli Tutti. Martin Luther King Jr. was formed not only by this Baptist vision of a civil order with the potential for including diverse others within the bond of human fraternity; he also was formed by the experience of being “othered” by a society in the Southern United States in which Baptists, white Baptists in particular, now were part of the religious and cultural establishment.

“The persecuted other had become centuries later the persecuting establishment.”

These white Baptists in the South had forgotten the biblical admonition from Leviticus: “The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt.” We might paraphrase: “for you were persecuted religious others in the land of England.” The persecuted other had become centuries later the persecuting establishment.

That experience, too, formed King, whose anthropological vision anticipated what we read in Fratelli Tutti. Pope Francis lists King first among the “brothers and sisters who are not Catholics” who particularly inspired him. Francis may have been inspired by King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail. In it, King wrote: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Advocates for the ‘other’

This is the relational theological anthropology that has led Baptists at our historical best to be advocates for fully including in a society of human fraternity everyone who has been “othered,” especially marginalized minorities, and to work for the just treatment of all persons in such a society. Fratelli Tutti can help Baptists in America embody that heritage more fully, and to repent of our failures to embody it.

As a Baptist ecumenical theologian, I note that the Vatican II Decree on Religious Liberty Dignitatis Humanae — which was conceived as an appendix to the Decree on Ecumenism Unitatis Redintegratio — had characterized religious liberty for the religiously other as the pre-condition of authentic ecumenical encounter. This ecclesial gift stewarded by the Baptist tradition has been received by the Catholic church. In the words of Francis in this encyclical, this is a liberty that is not “a condition for living as we will,” but “the richness of a liberty directed above all to love.”

This liberty is a gift that needs to be re-received by many Baptists in America. Reflection on Fratelli Tutti can help us do so.

Steven R. Harmon serves as professor of historical theology at Gardner-Webb University School of Divinity in Boiling Springs, N.C. He is author of Baptist Identity and the Ecumenical Future and co-editor with Amy L. Chilton of Sources of Light: Resources for Baptist Churches Practicing Theology. His newest book, Baptists, Catholics, and the Whole Church: Partners in the Pilgrimage to Unity, will be published by New City Press later this year.

Related articles:

Francesco will restore your faith in a broken church | Opinion by Craig Martin

Pope Francis calls for elimination of death penalty, and that’s only part of what he wants | Analysis by Aaron Coyle-Carr