By Jeff Brumley

Matt Cook says he frequently hears from fellow Baptists worried that the steady cultural shift away from church and faith may spell persecution for traditional Christians.

It’s a fear born of constant news reports and anecdotes about young people leaving congregations in droves, churches having to merge or close and fewer Americans being raised with any kind of God-consciousness at all, let alone a belief in Christ and his resurrection.

Cook, pastor at First Baptist Church in Wilmington, N.C., said his response usually is to explain that, while sometimes unsettling, such developments are a far cry from persecution — especially when considering the ongoing suffering of Christians and other religious minorities in places like Iraq and Syria.

“That [societal] shift is real,” Cook said. “But there is a significant difference between us becoming a more diverse culture and there being actual persecution in our culture.”

“That [societal] shift is real,” Cook said. “But there is a significant difference between us becoming a more diverse culture and there being actual persecution in our culture.”

The topic resurfaced earlier this month when Cook read an Alan Noble article in The Atlantic titled “The Evangelical Persecution Complex,” which lays out the tendency among conservative American Christians to see and claim anti-religious abuse at the hands of government, the courts, the gay community and others.

The rise of gay marriage and reports of Christian photographers being forced to shoot pictures at gay weddings are, some evangelicals contend, proof that Bible-believing Christians are squarely in the sights of an increasingly secular and pluralistic nation.

Cook was so moved by the piece that he posted it on Facebook and urged his friends to read it.

Cook was so moved by the piece that he posted it on Facebook and urged his friends to read it.

“Crying wolf on religious persecution is dangerous,” Cook said in a comment with the link. “It de-sensitizes people to the real thing around the world, and it runs counter to the whole idea of loving our neighbors as ourselves.”

While scholars who study religious persecution agree that claiming oppression where there really is none is dangerous, they also add that the phenomenon is practically inevitable — especially among Christians and even more so among American Christians.

It’s mainly, but not only, conservative Christians who make those claims in the U.S. nowadays. But others, including former Southern Baptist Convention members driven to create and join the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and other moderate movements, in some cases have clung to feelings and rhetoric consistent with victimhood from past events.

And no wonder: those experts say the need for persecution is built into the fabric of the Christian faith and that Americans love being David against Goliath.

Persecution narrative

It starts with Americans loving to be the underdog, said Noble, author of The Atlantic article and assistant professor of English at Oklahoma Baptist University in Shawnee.

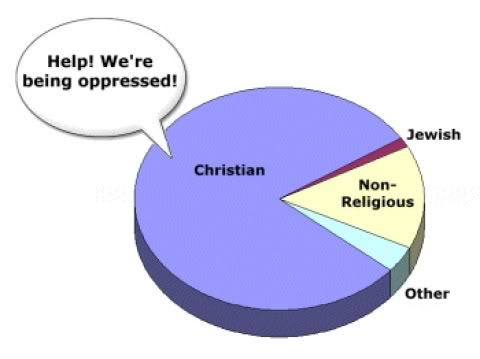

It’s how powerful members of government, the leaders of major Christian movements and an army of born-again bloggers can claim they and their followers are oppressed for their traditional biblical beliefs.

“Every group does this — everyone does this,” Noble told ABPnews/Herald. “We even have wealthy people who complain about being persecuted by tax laws that take their money and give it to the poor.”

The United States began as an underdog nation founded by persecuted people, which provides a handy narrative for any group when a court decision or election goes against them.

“Evangelicals have bought very uncritically in this very popular narrative,” Noble said.

Feelings of persecution are also common during church denominational shifts, and certainly were present during the conservative takeover of the SBC.

When liberals and moderates feel oppressed, Noble said, they tend to express it through social justice issues.

“That might go into advocating for the poor and minority groups,” he said.

Conservatives tend to funnel that fear into faith-based legal and political efforts — often with support generated by conservative media outlets that hype the persecution angle.

Another incentive to claim persecution is its connection to Christ, Noble said.

“For many evangelicals, the lack of very public and dramatic persecution could be interpreted as a sign that they just aren’t faithful enough,” Noble wrote in his article. “If they were persecuted, they could be confident they are saved.”

Christian DNA

But that’s nearly unavoidable, said Candida Moss, professor of New Testament and early Christianity at the University of Notre Dame.

Moss, an expert on the history of Christian persecution and martyrdom, said the religion itself is based on oppression and suffering.

Jesus told his followers to take up their crosses to follow him, and he was subsequently persecuted and crucified. Martyrdom stories about the apostles and later saints cemented that worldview, she said.

“So today, many believe they are persecuted — whether they are or they aren’t,” said Moss, author of the 2012 book Ancient Christian Martyrdom: Diverse Practices, Ideologies, and Traditions.

One way to determine if an individual or group is experiencing actual persecution, Moss said, is by examining the reactions of those experiencing oppression.

One way to determine if an individual or group is experiencing actual persecution, Moss said, is by examining the reactions of those experiencing oppression.

Around the world, those subjected to deliberate suffering at the hands of others are likely to emphasize, somewhat quietly, that they are not threats to those in power. These groups usually are too frightened to make caustic remarks or wage political fights against their oppressors, Moss said.

But when Christians, particularly in the West, are publically vocal about being persecuted, she said, “they usually are not.”

High-profile, high-volume claims of persecution make sense only from a position of relative social and political comfort and acceptance and when there is a sizeable “empathetic audience,” she said.

‘How foolish it was’

Even so, Christians must be careful not to hang onto those victim feelings too long, Noble added.

“The danger of this view is that believers can come to see victimhood as an essential part of their identity,” he said.

Cook, currently moderator-elect of the CBF, said he can identify with that after growing up amid the denominational battles that led to the migration of liberals and moderates from the SBC.

He watched his father, then an official with the Baptist Sunday School Board (now LifeWay Christian Resources), go through the roller coaster of job insecurity for years. This along with political upheaval at seminaries predisposed him toward a conflict-driven spirituality.

“I would say I spent the better part of my last years in college and first years in seminary looking for that controversy — going and looking for that fight — because I wanted to be in it,” Cook said.

But seeing how toxic that was for him, spiritually, led him to turn away from those battles. As he moved into a calmer faith, Cook said he saw how damaging his prior persecution complex had been to his relationship with God.

One result was to notice the genuine suffering of others, he said.

“Finally, I got to see how foolish it was to see myself as persecuted compared to other Christians globally,” Cook said.