“Never forget that the purpose for which we live is our improvement, so that we may go out of this world having, in a great sphere or a small one, done some little good for our fellow creatures and labored a little to diminish the sin and sorrow that are in the world.” — W. E. Gladstone

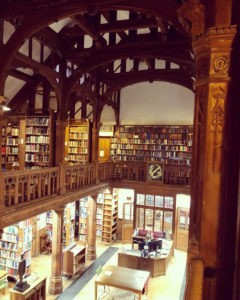

I write from Gladstone’s Library in Wales, the prime ministerial library established by and honoring William Ewart Gladstone, four-time prime minister of England.

Interior of Gladstone’s Library.

I am not simply thinking of Gladstone because his visage lurks around every corner. This weekend I was on BBC Radio Scotland talking with barrister and human rights advocate Baroness Helena Kennedy and with former primate of the Scottish Episcopal Church Richard Holloway about the massive current problem of competing rights: people on the opposing sides of Brexit, of abortion rights, of Black Lives Matter, of gun rights, of COVID-prevention, of almost every fraught cultural and political issue.

In response to this language of competing rights, I started by saying that those of us in the Christian tradition should speak less about rights and more about responsibilities — what is genuinely harmful to my neighbor may not be a right I should clutch tightfisted. Then it occurred to me that what we were really talking about, what we are actually in danger of losing in these divisive times of “my rights” and “my fears,” are traditional liberal values.

A few years ago here at the library, Martyn Percy, the dean of Christ Church Oxford, said that he considered the Brexit vote to be a stunning failure of liberal values. What he meant by “liberal” was not what we tend to think of in America, but what Gladstone meant, not liberal politics, per se, but liberality broadly defined: compassion for others, openhandedness, a responsibility to the greater good, a willingness to see all people as human and to at least consider their needs and desires in our decision making.

As we think about liberal values and the value of conversation to resolve these competing claims, it’s important to note that these fears and concerns are not necessarily created equal. Aquinas says it is possible to have an unreasonable fear, a fear that animates us, yet shouldn’t. Fear that becomes spiritually paralyzing despite its spuriousness. Someone’s fear of being forced to give up their assault rifles, for example, may be measured against my fear that I — or anyone else — will be killed by an assault rifle, since such weapons have been used in four of the five most lethal mass shootings.

When I see parents obsessing over what bathroom stall transgender kids can use or whether primarily peaceful Black Lives Matter protests might burn down their neighborhoods, I am seeing unreasonable fears, especially when compared to the opposing claims, to the fact that 2021 looks like the deadliest year of violence against transgender persons ever, or that the odds of being shot by law enforcement if you are doing anything while Black are at least three times greater than my chances.

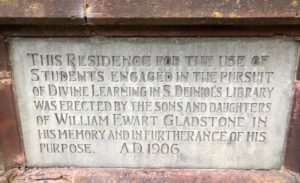

Dedication cornerstone at Gladstone’s Library.

What you’re probably noticing from examples like these is that the exaggerated fears on one side may actually drive very real harm against those on the other. So, if you are a privileged person (as I am, as many people complaining loudly about their rights are), then perhaps our wants, fears and perceived needs ought to be balanced against whether or not they cause harm to people who have been traditionally disadvantaged, those children of God that the Scriptures sometimes call “the least of these.”

We want what we want. But radical individualism — much more a part of the American ethos than the British — doesn’t sustain communities; it destroys them. Liberal values, on the other hand, make community possible. Ultimately, without liberal values, all of us suffer.

In war and in peace, it is sacrifice, compassion, mercy and shared responsibility that always have changed the world for the better. The world daily grows more fragmented, more dangerous and more selfish, and some days, I find myself becoming more hopeless.

But surely some hope remains.

War veterans’ memorial in Hawarden, Wales, outside Gladstone’s Library.

Sunday, when I was on the BBC in Edinburgh, was Remembrance Sunday, a UK holiday somewhat akin to our Veterans and Memorial Days. It is a day when all those who have died in the service of their country starting with World War I are remembered.

To be in the UK at such a time is to be staggered by the human cost of freedom. In Oxford, where I have spent much of the fall, every college and every church has a name-crowded war memorial lamenting members who fell in battle between 1914 and 1918. Just outside Gladstone’s Library, a poppy-garlanded war memorial remembers the ranks of local villagers who gave their lives in World War I.

There are similarly heart-stopping displays in every village and town throughout the United Kingdom. In railway stations and in banks, in fact, almost everywhere one turns, one finds memorials to those who died over a hundred years ago.

What is it that the British remember on Remembrance Sunday? Surely not the mismanagement of the First War, not the horrible human cost of a conflict that need never have been fought.

But Richard Holloway talked about remembrance simply and beautifully on Sunday morning: We want to remind ourselves that there once were multitudes of people who were willing to give themselves for something larger than themselves. Who were willing to put aside their own fears and their own desires for the common good. Who did not insist that their lives and their futures were all that mattered.

We call these being remembered heroes, and we may think of them as extraordinary, but truly, their calling is also ours: to leave the world a little better than we found it, to make a difference in the lives of others, to diminish the sin and sorrow that are in the world. And that can only be done with liberal values.

“Fear causes us to live contracted little lives.”

Fear causes us to live contracted little lives; selfishness makes our hearts three sizes too small. But Jesus called us to love extravagantly, and Gladstone argued that liberal values call us to recognize that every human life has ultimate value: “All human beings have the same claims upon our support,” he said. “The ground on which we stand here is not British or European, but it is human. Nothing narrower than humanity could pretend for a moment justly to represent it.”

Rights language causes us to build walls and sacrifice connection, to balance awkwardly on our own tiny patch of ground, but remembrance reminds us: We are called to something bigger, to something better, and our lives are bound up with each other.

Greg Garrett is an award-winning professor at Baylor University. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of more than two dozen books, most recently In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is currently administering a research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and writing a book on racial mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and Theologian in Residence at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

The pandemic of the unclaimed dead | Opinion by Harold Ivan Smith

Conservative Christianity as threat to democracy | Opinion by David Gushee

A wish list for the common good in a new era | Opinion by Marv Knox