An Alabama court’s recent decision deeming frozen embryos “extrauterine children” resulted in the shutdown of several prominent IVF clinics. While many conservative Christians were pleased to see the cessation of invitro fertilization in the state, just as many were left confused.

Why would a group who claimed to be “pro-life” and “pro-family” not support a procedure designed to bring a new life into a family?

“I never thought (IVF) was so polarizing. There’s mamas who I just truly believe are meant to be mamas that can’t do it without IVF,” said Hannah Nelson, speaking to the Washington Post. Nelson is part of the 2% percent of Americans who have used IVF to conceive. With IVF now an established component of reproductive medicine, its controversial beginnings have largely been forgotten.

In the Alabama case, a clinic patient wandered into the embryo storage area and accidentally dropped a container of frozen embryos, destroying them. That wouldn’t have happened during the early 1980s at what would become the Jones Institute for Reproductive Medicine in Norfolk, Va.

Samuel Marynick, director of the Texas Center for Reproductive Health, remembers his visit there: “Security was present. Different areas of the reproductive center at the institute had doors mislabeled to throw off curious outsiders. For example, the embryology laboratory had a door label that said, ‘Soiled Linen.’”

Early protests

Such obfuscation was necessary inside the building because of the anti-IVF protests going on outside.

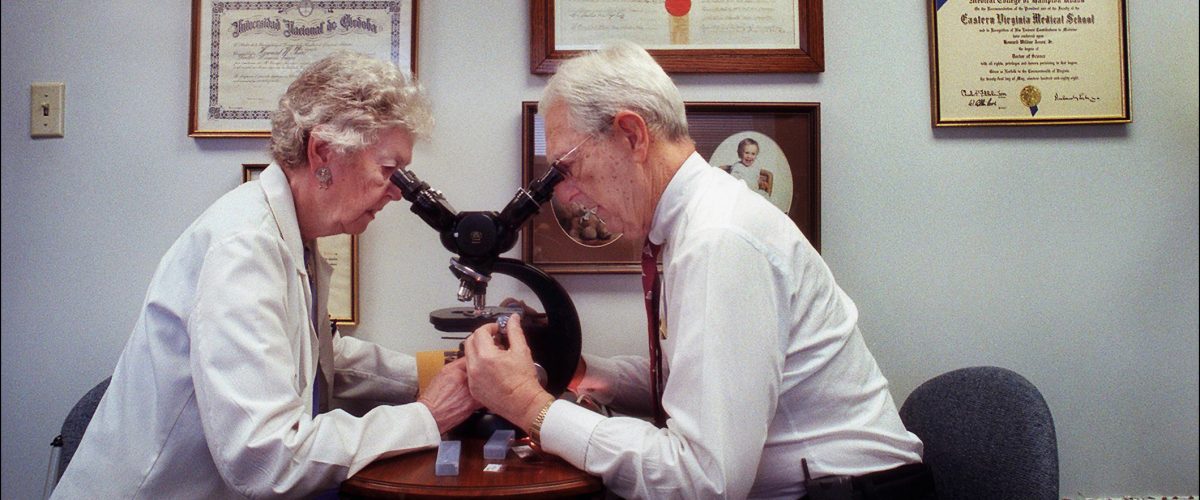

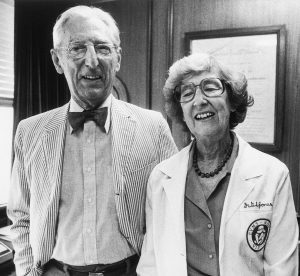

When gynecologists Howard and Georganna Jones moved to Norfolk from John Hopkins University in 1978, they didn’t plan to open a test tube baby clinic and become medical pioneers. They started the clinic at the Eastern Virginia Medical School. (Getty Images)

The Joneses behind the Jones Institute were Howard and Georgeanna Jones, who had come from Johns Hopkins to Virginia in 1978 to establish the Department of Reproductive Medicine at the new Eastern Virginia Medical School. Georgeanna Jones was one of the country’s first reproductive endocrinologists. Her husband, Howard Jones, was a renowned gynecologist and surgeon.

“We did not come with the idea of setting up an in-vitro fertilization program,” said Howard Jones. However, as movers began unloading the Joneses’ furniture, news broke that a colleague in the UK, Robert Edwards, had successfully delivered the world’s first “test tube” baby.

“The day the birth of Louise Brown was announced, I received a call from an NIH official freezing (research) funds,” Jones said. “It was clear that some members of Congress were upset by the demonstration that a new individual could be created in a test tube.”

As the UK and Australia continued to make advances in reproductive medicine, America lagged behind. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade complicated matters when it sided with a woman’s right to reproductive freedom over arguments for fetal personhood. The very next week, Republicans in Congress proposed the Human Life Amendment, which granted equal protection under law to every human being “from the moment of conception.” They also passed a moratorium on IVF research in 1975, which made it illegal to even speak about human IVF at federally funded conferences.

They also passed a moratorium on IVF research in 1975, which made it illegal to even speak about human IVF at federally funded conferences.

When a local reporter asked Jones if it would be possible to produce a test tube baby in Norfolk he said, “Sure. The only thing it would take would be a little money.”

Fortunately for the Joneses, a former patient of Georgeanna’s saw the newspaper article and provided the couple with enough funding to begin clinical trials. Howard Jones recalled: “When it became known that we were to do this, we ran into opposition from a completely unexpected source.” The hospital associated with the medical school would need a special permit, a “Certificate of Need,” issued by the state, which required a public hearing.

What normally would have been a dull, bureaucratic meeting at the Norfolk Health Department turned into a full-blown media circus. “The hearing lasted for six hours. The opposition was quite organized. They brought in large numbers of people from out-of-town,” he explained.

The Right-to-Life protesters accused the doctors of “playing God” and “interfering with God’s will.” They hurled insults at couples on the opposite side of the auditorium whose names were on the waiting list for IVF.

“Incredible claims were made,” wrote Howard Jones in his memoir. “Protesters (said) that in-vitro fertilization would surely promote incest, human-animal hybrids, and other bizarre scenarios which were both shocking and unbelievable.”

Despite the protests, the commissioner of health granted EVMS the permission to begin IVF procedures in patients.

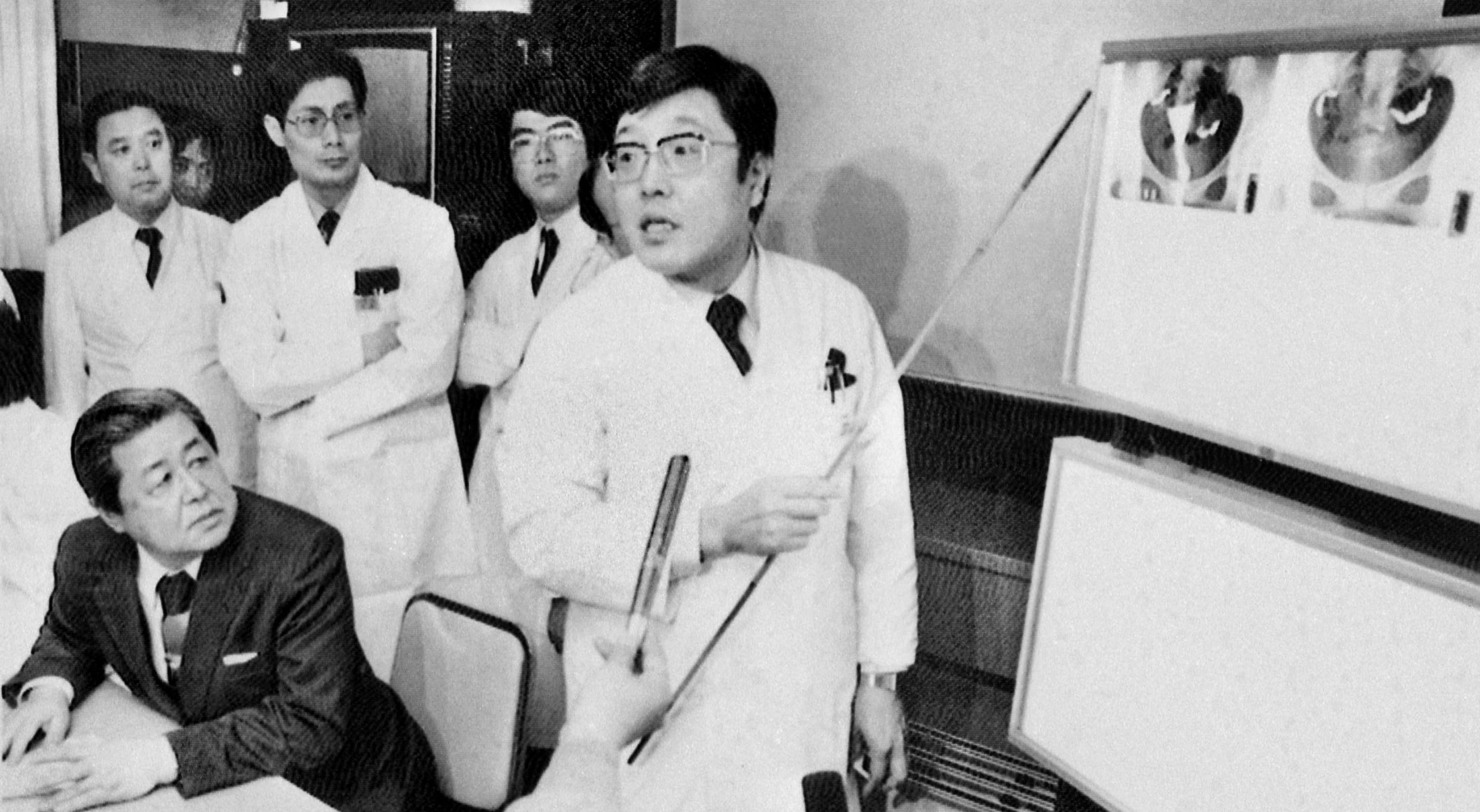

In March 1983, a team of fertility specialists at Tohoku University, led by Masakuni Suzuki (in suit seated L), announce their success in Japan’s first in-vitro fertilization, at the university in Sendai, northeastern Japan. (AP photo)

More protests

Protests in the media and in front of the medical school continued unabated. When another local paper published an editorial claiming the Joneses would force women carrying “abnormal” fetuses to abort them, the doctors sued the paper for libel. The settlement was enough to fund the clinic for several years.

The first patient to receive IVF at the new clinic was Sarah Houck. She and her husband walked by picketers several times a day while Sarah was receiving treatment.

A cutting from the Daily Mail newspaper dated July 1978, which forms part of the Lesley Brown archive, a collection of items kept by the mother of the world’s first test tube baby, Louise Brown. (Ben Birchall/PA Wire/AP Images)

“They were protesting loudly, screaming negative things and this kind of stuff. They were yelling, ‘Incest, incest, the whole world will be in-vitro.’ I couldn’t believe people were so mean,” Houck said.

The main objection of religious protesters, then as now, was the potential destruction of embryos that might occur during the process, which they considered akin to abortion.

Howard Jones acknowledged that not every embryo would be implanted nor would every implanted embryo carried to term. However, he said these were “not the kind of abortions one usually envisions,” but “the loss of free-floating fertilized eggs, which mostly perish as a microscopic ball of cells.”

Embryo loss is common, even without IVF. In real life, 60% of embryos dissolve before people are even aware they are pregnant, and another 10% are lost through miscarriage.

“On average, only one in five meetings of sperm and egg result in a fertilized egg with pregnancy potential.”

“Human reproduction is an inefficient process,” Jones said. “On average, only one in five meetings of sperm and egg result in a fertilized egg with pregnancy potential. So therefore, ‘normal’ is the abnormal. When you try to do IVF, you are grafting an inefficient process on an inefficient process.”

A breakthrough

After 41 failed attempts to achieve a pregnancy, Georgeanna Jones made a breakthrough. Rather than depend on the monthly release of a single egg, she would use hgM, human menopausal gonadotropin, to stimulate the release of multiple eggs in a patient. In March 1981, Judy Carr began treatment with this new method and became pregnant through IVF soon after.

Father and baby Elizabeth Jordan Carr (first test tube baby) in delivery room with camera crew, Norfolk General Hospital, Norfolk, Va., December 21, 1981. Courtesy of The Virginian-Pilot. (AP Photo/Virginian-Pilot)

Carr was from Massachusetts, where IVF was illegal, so she flew to Norfolk for her monthly checkups. She remembers the precautions taken around her pregnancy. “The first time, Dr. Jones asked how I got to the hotel from the airport, and I said I took the airport shuttle. And he said, ‘Well, you won’t be doing that again,’ and from then on, he picked me up at the airport in his 15-year-old station wagon.”

During the final month of her pregnancy, Carr and her husband rented a condo in Norfolk under an assumed name. When the first IVF baby was born in the UK, the mother received bomb threats at the hospital. These turned out to be hoaxes, but the Joneses were taking no chances.

The hospital stationed armed guards in the hall outside the delivery room. A film crew from the public television show Nova was on hand to document the birth. If things went wrong with the delivery or the baby, Howard Jones had prepared a statement in his pocket to read to the press.

“The note said: ‘We had been terribly distressed to find that the child was abnormal, and we request privacy for the family. We (have) three other pregnancies en route and they all seem to be normal, and we hope this individual situation was [a} single aberration.’”

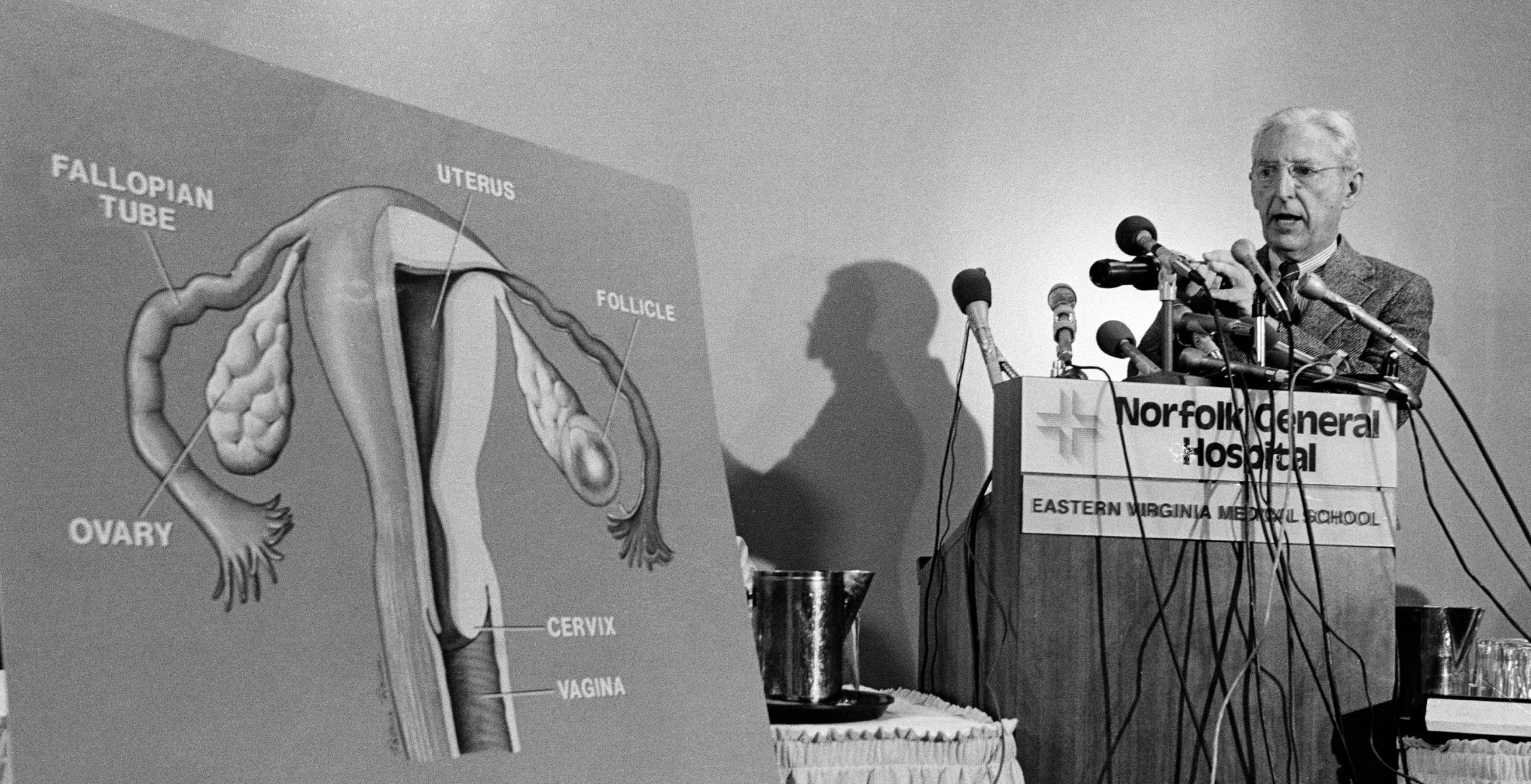

Fortunately, the statement wasn’t necessary. Elizabeth Carr was born Dec. 28, 1981, two days before Howard Jones’ 71st birthday. After this success, the waiting list for IVF at what in 1983 would become the Jones Institute for Reproductive Medicine doubled.

At the Vatican

In 1984, Georgeanna and Howard Jones attended a symposium of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences held at the Vatican which purported to be a “search for truth” regarding in-vitro fertilization. However, the Catholic Church ignored the Joneses’ scientific contributions to the conversation and doubled down on its belief that IVF “establishes the domination of technology over the origin and destiny of the human person” and was “corrupted by an abortion mentality.”

Howard Jones never looked down on the religious groups that protested IVF but felt their position was based on a misunderstanding of the science of reproduction. He authored several books, including Personhood Revisited: Reproductive Technology, Bioethics, Religion and Law, which examined both scientific and religious texts in the hope of better explaining IVF.

“The opposition to IVF has faded through the years — not disappeared, but faded,” he said. “I believe the reason for that is that IVF works.”

Howard W. Jones explains the in vitro fertilization process during a news conference at the Norfolk, Va., General Hospital, Dec. 28, 1981. Jones announced the birth of Elizabeth Carr, America’s first test tube baby. (AP Photo/Steve Helber)

Meeting the Joneses

I had the opportunity to interview Howard Jones and meet Georgeanna Jones when working for public television in Norfolk, Va. Both were in their late 80s and still sharing an office at the Jones Institute. Georgeanna Jones already was experiencing dementia at that time and no longer practicing medicine, but Howard Jones was adamant that their success with IVF would not have happened were it not for her contributions to the process.

Georgeanna Seegar Jones, left, and her husband, Howard W. Jones, talk to reporters during a news conference announcing the birth of the nation’s first test tube baby in Norfolk, Va., Dec. 28, 1981. (AP Photo/Steve Helber)

His passion for his medical calling as well as his abiding compassion for his patients was evident during our conversation. I agree with historians of IVF who say Georgeanna and Howard Jones, a married couple who appeared as doting grandparents to generations of IVF children, had a moderating influence on the initial flurry of right-wing religious protests in the 1980s and beyond. Howard Jones was an active participant in the arena of reproductive medicine, speaking at conferences and authoring several more books until his death in 2015 at the age of 104.

It remains to be seen if anyone will be able to take the Joneses’ place in the surging new debate.

Because of their lifelong commitment to science and patient well-being, for more than 40 years Americans have accepted IVF as standard care for infertility. There is still the occasional protester outside the Jones Institute (now managed by Shady Grove Fertility) but now Christians who object to IVF are largely looking to courts like the one in Alabama to do the work for them.

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary President Al Mohler, supported the Alabama ruling saying, “IVF technology requires the moral alienation of goods that God intended to come together.” He also objected to IVF because the procedure is used by same-sex couples and single women to have children.

While Alabama’s governor has since signed a stopgap measure to protect IVF providers, the new law is still subject to the state’s constitutional protection for “unborn life” and does not address the status of “extrauterine children.” Legal and practical questions surrounding IVF in Alabama are far from settled.

Kristen Thomason is a freelance writer with a background in media studies and production. She has worked with national and international religious organizations and for public television. Currently based in Scotland, she has organized worship arts at churches in Metro D.C. and Toronto. In addition to writing for Baptist News Global, Kristen blogs on matters of faith and social justice at viaexmachina.com.

Related articles:

Alabama politicians flee IVF backlash

IVF, CPAC and MAGA: Christian nationalism erupts to the surface | Opinion by Robert P. Jones

A deeper look at Alabama judge Tom Parker and his desire for the righteous to rule America