The restorative justice process used to rehabilitate criminal offenders and bring healing to victims also can be used to foster forgiveness and compassion within families and faith communities, an expert on the practice said.

“When you have the experience of actually forgiving someone in your life, it’s helpful for them, but it’s also helpful for you,” said Lindsey Pointer, principal investigator with the National Center on Restorative Justice and assistant professor in restorative justice with the Vermont Law and Graduate School. She spoke during a recent webinar hosted by Equal Justice USA.

Restorative justice employs practices to promote accountability and identify the root causes of criminal acts on the part of offenders, while naming the needs and repairing the harms experienced by victims, Pointer said during the webinar moderated by EJUSA’s Sam Heath.

Lindsey Pointer

“One of the things that is of benefit about restorative justice is it helps create those ingredients, or that kind of structured experience, that can lead to genuine forgiveness, which can be of great benefit to people who have experienced significant harm,” Pointer said.

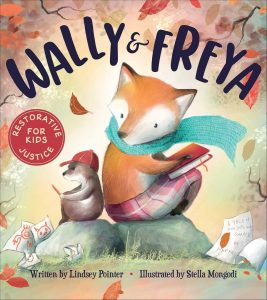

She is the author and co-author of several books on restorative justice, including Wally & Freya, a children’s book in which a group of small animals learn to forgive a bully for refusing to share crayons and for stealing a notebook they needed to write a story.

The idea was to teach children — and the parents reading the book to them — how to apply restorative justice principles such as empathy and compassion in situations in which one or more people have experienced harm, she said.

“Children’s books and children’s media in general are kind of brilliant because you can tackle something huge but in a really small package. It’s about finding little ways of capturing stories that then speak to broad universal themes.”

Those themes are operative as much on the family and congregational level as they are in criminal justice settings, she added. “In some ways, it can be the more challenging area of application because conflict and harm are messy and complicated in our lives, and you’re dealing with relationships over years and years and there’s all these other factors.”

Numerous resources are available to those interested in practicing restorative justice, including The Little Book of Restorative Teaching Tools: Games, Activities and Simulations for Understanding Restorative Justice Practices, which Pointer wrote with Kathleen McGoey and Haley Farrar.

“One of the threads in the restorative justice movement that is strong right now is people are seeing it as a way of life and bringing it into all areas of their lives, bringing it into families, bringing it into workplaces, bringing it into spiritual communities,” she explained.

A core principle of restorative justice is not to equate the offender with the offense, she added. “It is understanding that a person is whole and wonderful and separate from a behavior that is harmful. It is understanding the needs behind the behavior, pausing and having that centered kind, calm, compassionate curiosity, and then finding creative ways of healing that can meet everyone’s needs.”

A core principle of restorative justice is not to equate the offender with the offense, she added. “It is understanding that a person is whole and wonderful and separate from a behavior that is harmful. It is understanding the needs behind the behavior, pausing and having that centered kind, calm, compassionate curiosity, and then finding creative ways of healing that can meet everyone’s needs.”

Pointer cautioned that living by restorative justice principles can be challenging in a culture steeped in adversarial and punitive narratives around criminal acts and other forms of harm.

“It’s the villains-and-heroes, good guys-and-bad guys thing. That’s a central theme to a lot of stories we share with our kids. And it takes a lot of rewiring in your brain to stop thinking about it as villains and heroes or good guys and bad guys, and instead think about the need at the root of this harmful behavior and how we can respond in a compassionate way. That will make us a more connected and caring community rather than just pushing that person out, which we know will just have additional ripples of harm.”

In the home, the practice can be difficult as parents and children alike must learn to assess and express feelings when conflicts arise, Pointer added.

“It looks a lot like developing vocabulary for talking about emotions and taking the time to help our children regulate so they are in a calm enough space to identify and talk about their emotions when something difficult happens. And then it’s also about finding ways to support both ourselves as parents and young people in truly repairing harm when it does happen.”

And parents must be nondefensive when modeling the practice of acknowledging and apologizing for mistakes, she said. “We have to say to our kids, ‘I am sorry I lost my temper. I shouldn’t have yelled. What can I do now to make you feel better? What do we need to move through this?’ And we must follow through on that and help support kids to do that when they cause harm to each other, as well.”