If United Methodists are to fulfill the church’s current mission to dismantle racism, then its white members must come to terms with the denomination’s racist history, contends author John Elford.

Elford’s conviction spurred him to write Our Hearts Were Strangely Lukewarm: The American Methodist Church and the Struggle with White Supremacy. Now he hopes the book, a deeply researched dive into American Methodism’s complicity with racial oppression, likewise will encourage its readers “to find ways to get involved in antiracism work in their church and community,” he said.

The book’s title plays off John Wesley’s account of his personal experience of salvation, when he wrote that his heart “felt strangely warmed” by the knowledge that he trusted Jesus Christ for his soul’s salvation.

Johh Elford

In a season when several authors have brought out books related to white supremacy and Christian nationalism, Elford’s history still may be uncomfortable for many white United Methodists, especially families with many generations’ heritage in American Methodism. Yet he remains convinced now is the season when white Christians must atone for the pain caused by the church’s racist past and focus on building a future free of racial oppression.

“That would be my first and best hope, if dismantling racism could become part of who we are, an essential part of being a Christian, instead of just a project as it is now,” the author said.

Pastor emeritus of University United Methodist Church on the University of Texas campus in the state capital of Austin, Elford credits the congregation’s longtime social justice activism as a major force behind his book.

“Speaking out against injustice was a job requirement” as pastor, Elford said.

Two other influences galvanized the author: discussions about local injustices held in a racial justice group at University UMC, and another book, White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity, by Robert P. Jones, founder and president of Public Religion Research Institute.

“White Too Long was like an altar call for me,” Elford said. “Robby writes from his Baptist background, but the depth of churches’ complicity with racism was astounding.

“White Too Long was like an altar call for me,” Elford said. “Robby writes from his Baptist background, but the depth of churches’ complicity with racism was astounding.

“Still, I wondered what happened in the Methodist Church,” said the author. “I found even people who’d been in the United Methodist Church 40 or 50 years, who lived through the Civil Rights era, don’t know the church’s problematic history with racism.”

Elford pulls no punches in describing how American Methodism’s racist roots go deeper than the few incidents some may know. One of the more prominent historical events birthed the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which emerged after Richard Allen and other Black Methodists were denied Holy Communion at St. George’s Methodist Church in Philadelphia.

Elford writes of the beginnings of Methodism’s racism: “Just as the nation struggled with the paradox of enslaved peoples in a free land, so did the church. John Wesley could not have made it any clearer that slavery was not only inconsistent with any notion of justice but also that fierce opposition to it was the only position possible for those who trusted in the grace of God offered to all. Yet, in the decades following Wesley, the Methodist Church would find itself so entangled with the institutions of slavery and racism that it often functioned not so much as a transformer but as a transmitter of the evils of slavery and white supremacy.”

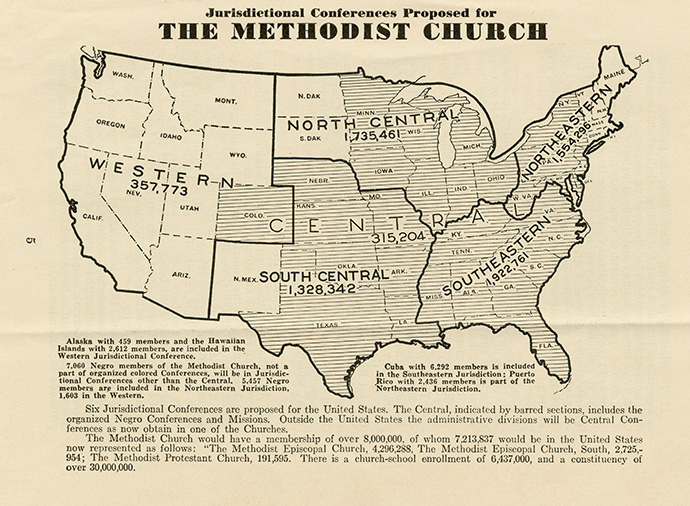

Map illustrating the proposed jurisdictional conferences for the 1939 merger creating the Methodist Church. Five of the jurisdictions are based on geography, while the shaded area representing the Central Jurisdiction would segregate African-American Methodists from the rest of the denominational structure. (Map courtesy of Pitts Theology Library, Emory University.)

The retired pastor said he was able to draw upon many sources to trace Methodism’s involvement with racial oppression. For example, he cited the academic works of Methodist historian Russell Richey; the archives at UMC-related Drew University in Madison, N.J.; and the assistance of Ashley Boggan D, top executive of the General Commission on Archives and History.

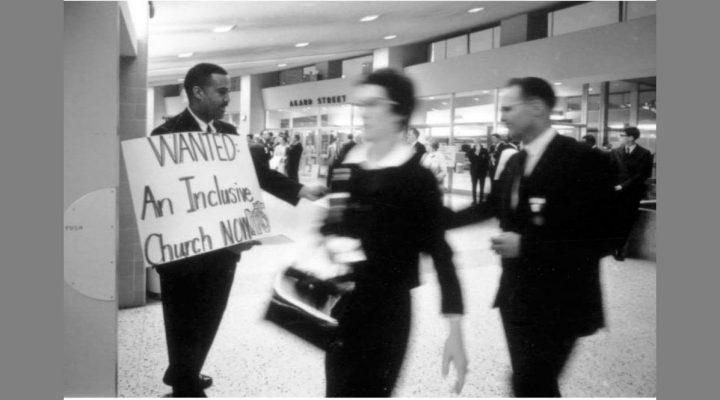

The author also credited Ed King, the white Methodist chaplain at church-related historically Black Tugaloo College in Jackson, Miss., as another bountiful resource. King gave the author several journals documenting the “kneel-ins” he led in the 1960s in attempts to integrate Southern Methodist churches.

As he got deeper into his project, Elford said he found himself appalled at times by what he discovered.

The merger of the Methodist Church and the Evangelical United Brethren Church in 1968 brought together two traditions but also provided an opportunity for the Methodists to leave behind a heritage of segregation. (Photo from Methodist Commission on Archives and History)

“Sometimes I’d read accounts of events and wonder how they could have happened in the Methodist Church, like the entire era of Methodists doing little or nothing about pastors owning people,” Elford said. “It wasn’t really until the 1840s that the church began to think about taking a harder line on slavery.” (The Methodist Church split into northern and southern branches over slavery in 1844).

Elford said another key insight came from stories about racism that happened in local congregations. He found one such unsettling example in a story from Fairlawn Community Methodist Episcopal Church in New England.

“They opened the 1920 cornerstone and found Ku Klux Klan literature in the capsule,” he said. “In the church!”

A blasé attitude toward lynching in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in both the northern and southern branches of Methodism also disturbed him, Elford said.

Thankfully, his research also found instances of “phenomenal courage” in confronting racism.

“For example, Methodist women formed some of the first anti-lynching organizations,” he said. “Methodist women also kept pushing the church to think and talk about what it might mean to integrate.”

The author said he recognizes church members, still recovering from the strains of the coronavirus pandemic and this summer’s climate crisis, may feel they don’t have the emotional energy to tackle the continuing problem of racism. Nonetheless, he thinks his book is coming out at a good time for the UMC.

“As we reconceive the church after splintering, we need to look more at our own racism,” he said.

“As we reconceive the church after splintering, we need to look more at our own racism,” he said.

The General Commission on Religion and Race — the racial justice body formed after the 1968 merger that created today’s United Methodist Church — agrees with him, Elford said.

“GCORR thinks it’s history we need to know as we go into 2024; they’re preparing a study guide,” the author said.

Elford acknowledged there’s sometimes resistance to uncovering the UMC’s racist past because it “makes the church look bad.” Still, he’s hopeful current support for antiracism efforts and his deep dive into Methodist racial history will overcome that resistance.

“This is intentionally a white pastor writing to white Methodist congregations,” he said. “The white perspective is needed because we created the problem of white supremacy, and we need to fix it. We need to stop asking people of color to help us. White people need to do the work.”