“Write a sermon on this week’s lectionary text.”

“Write a Country and Western song about Job.”

“Write a prayer for Reddit.”

“Write a Bible song about ducks.”

“Add a prayer to go with that sermon.”

“Write a worship song about Jesus’ death and resurrection.”

“Generate a chord chart for that song.”

“Write a liturgy for a pet funeral.”

“Write a Bible verse in the style of the King James Bible explaining how to remove a peanut butter sandwich from a VCR.”

All these were commands given to ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence system made available for free to the public Nov. 30, 2022. Serendipitously, the day before ChatGPT’s release, Nov. 29, the Divinity School at the University of Edinburgh hosted a conference, AI and Pastoral Care for Christian Churches, a dialogue between theologians and engineers on the potential use of AI in parish ministry.

AI and pastoral care

Simeon Xu

While ChatGPT might possess the ability to compose a silly song or a mediocre sermon, something as deeply human as providing spiritual care appears, at first glance, beyond its purview. But as convener Simeon Xu said in his opening remarks, “Intelligent machines and robots force us to think more deeply about who we are as interactive beings and the partners of God.”

ChatGPT and other forms of AI might just become the local pastor’s new partner in ministry.

If AI can write a sermon, a praise song, a prayer and a pet funeral liturgy, what can it do for pastoral care? Pastoral care is the help that trained clergy provide to congregants from a theological or spiritual perspective and can run the gamut from questions of faith to family conflict.

Todd Thomas

“Pastoral care is an intrinsic facet of the work of all Christians, lay and ordained, as love for one another is the most consistent basis for all we should say and do, especially within the Body of Christ,” according to Todd Thomas, rector at St. Timothy’s Episcopal Church of Washington, D.C. “It’s the authentic way (pastors) share life with the parish and all their neighbors. It’s the reason a parishioner comes to them when they have questions, struggles, successes and joys.”

Eric Stoddart

So, can a chatbot be pastoral? Can it care? Eric Stoddart, professor of practical theology at the University of St. Andrews, raised these questions when he replaced the Good Samaritan in Jesus’ parable with a drone from “Samaritans R Us,” a subscription rescue service. Stoddart then asked attendees in Edinburgh, “Who was this man’s neighbor? Is this compassion? Is this care? What if a passing Samaritan initiates the call to the rescue service?”

Will technology be just another means to ministry for pastors, or does it have the potential to replace them?

Not a new idea

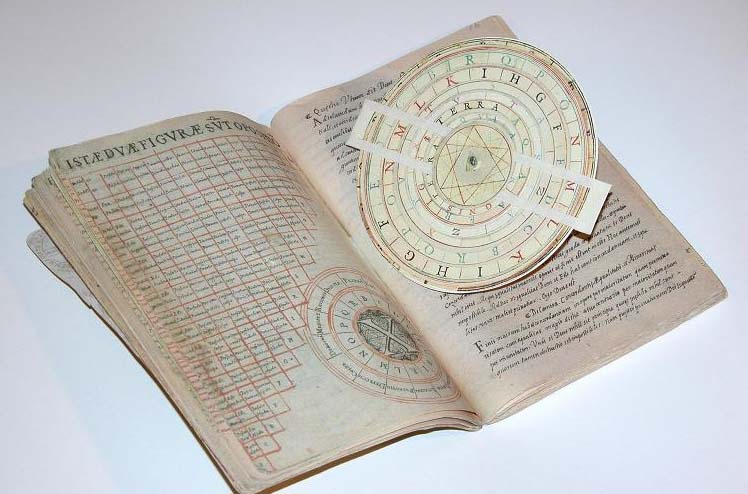

Professor Emeritus George Coghill, who retired from his position as head of computing science at the University of Aberdeen and is now pursuing a degree in theology, believes the convergence of technology and Christianity is nothing new.

George Coghill

“The earliest realistic attempt at something was the Ars Magna,” he said. This device was created in the late 1200s by Spanish mystic Ramon Llull, a missionary to the Moors in Southern Spain. “He took the three main religions — Judaism, Christianity and Islam — and he had them on different discs. And the idea was that theologians from the three religions could get together, use this instrument and come to a peaceful, absolutely resolute conclusion. Didn’t work. But it was the first real attempt at something automating reasoning and it was done within a Christian theological context.”

Ars Magna

Three hundred years later, “robotic” statues of the saints and the Virgin Mary inspired devotion as they ambulated, wept and gave blessings to believers. Powered by steam, water or clockwork, these 16th century wooden figures relied on a complex system of cogs, straps and hinges to move.

The most well-known of these is a monk created at the behest of Phillip II to thank God for his son’s miraculous recovery from a traumatic brain injury. Once wound, the 15-inch “monkbot” moves about on wheels hidden beneath his cassock, beats his chest, kisses his rosary and moves his lips as if in prayer. This clockwork “mini monk” modeled praying without ceasing and reminded parishioners of the prince’s miraculous healing

Many pastors and lay leaders already use modern technology in a variety of ways to assist in their ministries. COVID increased churches’ reliance on technology exponentially. Committee meetings, counseling sessions, weddings and funerals all moved to online platforms such as Zoom that let participants interact via video and text.

Many pastors and lay leaders already use modern technology in a variety of ways to assist in their ministries. COVID increased churches’ reliance on technology exponentially. Committee meetings, counseling sessions, weddings and funerals all moved to online platforms such as Zoom that let participants interact via video and text.

Second Life

Soon these events may exist in virtual reality spaces where participants interact with one another through avatars. The website Second Life already hosts dozens of virtual reality churches where avatars meet to worship, hold Bible studies and pray together.

Thomas previously hosted two different churches in Second Life, one in a virtual medieval cathedral and the other a smaller virtual gathering of friends. “We read scripture, listened to and prayed over the things happening in everyone’s lives, both in Second Life and real life, heard some prerecorded music and I preached,” he explained.

While the use of avatars may seem strange to churchgoers used to face-to-face interactions, research shows the human brain quickly adapts and begins to regard the avatars as real people evoking genuine emotions. Thomas’ experience reflects this.

“Our times together were their church; we were their community of faith,” he said. “Their needs were authentic and real, and I believe our prayers were heard.”

Virtual reality also presents pastors with an opportunity to be more sensitive to the diverse members of their congregations. Because individuals can be creative in the construction of their avatars, it may allow for greater self-expression and openness in matters of pastoral care. Avatar creation also allows transgender people to create virtual representations to match their gender identities and express this identity in a safe space.

Another potential AI-assisted ministry holds is helping neurodiverse individuals receive the pastoral care they need. A University of Connecticut study found people with autism preferred communicating with a non-human avatar like a robot or cartoon animal, because they didn’t have to worry about decoding human social cues.

ChatGPT and other advanced forms of AI are offering ministers another tool, one that combines the inspiration of the monkbot and the calculation of the Ars Magnus with modern technology.

“A major learn for me in that process of hosting services in Second Life was the realization of just how high a percentage of the global population using their service was in some way neurodivergent, dealing with strong anxieties or in differently abled bodies, all circumstances which greatly limited their comfort or desire to engage in the same activities in real life,” Thomas said.

In essence, ChatGPT and other advanced forms of AI are offering ministers another tool, one that combines the inspiration of the monkbot and the calculation of the Ars Magnus with modern technology.

Beyond Siri and Alexa

Chatbots themselves are nothing new. Virtual assistants Siri and Alexa are familiar chatbots that already help us make phone calls, search the internet and field simple customer service questions on various websites. What these basic bots cannot do is answer open-ended questions or create new content.

ChatGPT, which stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer is, as its name suggests, generative AI, meaning it generates brand-new material from the hundreds of billions of pages of text found online in digitized books, news sites, blogs, Wikipedia and social media. By mapping the relationships between various pieces of information, ChatGPT learns to predict what comes next in the sequence and provides the answer to the original command in natural-sounding sentences.

Because ChatGPT has mapped information about psychotherapy on the internet, individuals are beginning to use it as a mental health tool. The chatbot’s ability to remember details from session to session, its around-the-clock availability, and its affordability when mental health is excluded from most insurance plans, also makes it an attractive option for those seeking help.

ChatGPT is the most recent example of AI as therapist, but not the only one. A team of Stanford psychologists and AI experts created Woebot, a “talk therapy chatbot” that utilizes Cognitive Behavioral Therapy methods to help users suffering from depression. Students who tested the technology saw a 20% improvement in their symptoms after two weeks of use.

Another promising AI therapist is “Ellie,” developed by the USC Institute for Creative Technologies to help veterans suffering from depression and PTSD. Funded by the U.S. government, Ellie has the added ability of being able to read 60 non-verbal cues a second, including a patient’s vocal tone and facial expressions. To engage with Ellie, veterans interact with an on-screen avatar who presents as a female human but is completely AI. Most people using Ellie report they prefer her to a human psychologist, and studies of other AI therapies have concluded the same. Patients report feeling less judged and more at ease revealing personal information to an AI avatar as opposed to an actual person.

When an avatar’s characteristics such as age, gender or race are adjusted for user preferences, engagement with the avatar is even greater.

Taking faith into account

Ilia Delio

Ilia Delio, a Franciscan nun who holds a chair at Villanova University, thinks an adaptable avatar might be useful to the Catholic church. “It’s very male, very patriarchal, and we have this whole sexual abuse crisis. So, would I want a robot priest? Maybe! A robot can be gender neutral. It might be able to transcend some of those divides and be able to enhance community in a way that’s more liberating.”

While the Woebot and Ellie are offering care without any spiritual direction, Northeastern University and Boston Medical have developed an AI system that takes faith into account when helping users make decisions about palliative and end-of-life care. In addition to managing clinical issues such as pain and medication, the AI chatbot also helps users consider their “spiritual goals and values” using a dialogue of multiple-choice questions. During development of the system, researchers studied the willingness of older adults to discuss “preparation for death and spiritual counseling” with the chatbot and discovered that after speaking to the program’s avatar for 30 minutes, patients’ anxiety around death decreased significantly.

The palliative care chatbot relies on a broad understanding of various religions, so its guidance is limited. Generative technology like ChatGPT has the potential to provide more nuanced pastoral care. Because this technology creates content from the material provided to it, shaping the AI’s response is just a matter of feeding it sources curated around a particular point of view.

Theoretically, a chatbot could be assembled that would answer believers’ questions from a Baptist perspective. Christians could receive inspiration from a historical figure like Martin Luther King Jr., bereavement counseling from John Claypool, or encouragement from Corrie ten Boom by means of chatbots who have absorbed their sermons, speeches and books.

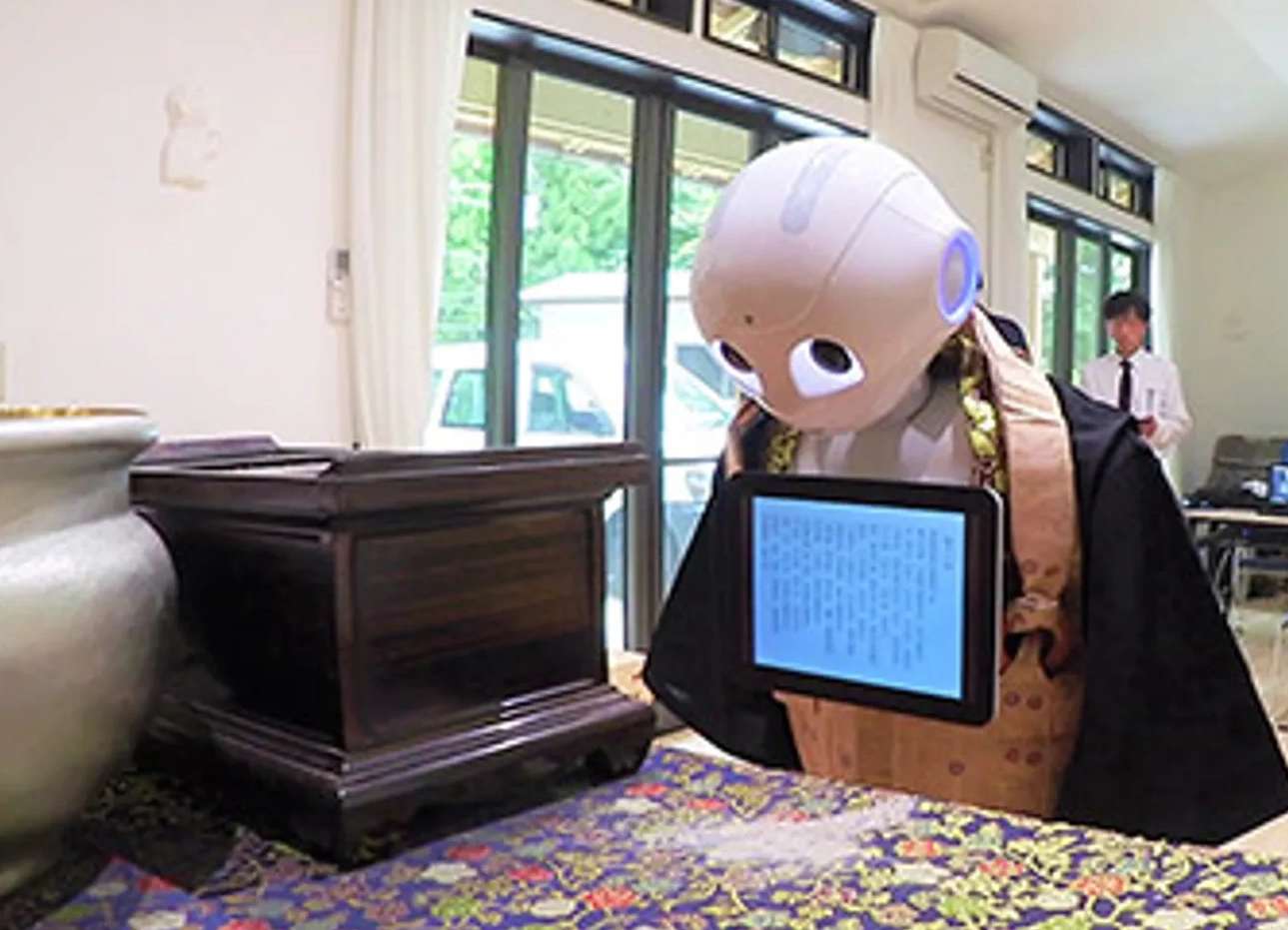

Once generative technology is more affordable, pastors could upload their own sermons, blogs and Bible studies to create a chatbot of themselves that would offer pastoral guidance to church members who are reluctant to share personal concerns with their actual pastor. In the near future, small churches unable to afford a full-time minister could access a chatbot when their bivocational pastor is unavailable. Even now, citizens in Japan are using “Pepper,” a robotic priest, when they cannot afford a human priest to perform funeral rites.

The downside

Before any clergy members start fearing for their jobs or finance committees begin budgeting for a bot, it’s necessary to look at the downside of ChatGPT and other AI systems.

Generative technology makes estimated guesses, and sometimes those guesses are wrong. ChatGPT does not create with any plan or purpose in mind; it pulls together words and information based on linguistic patterns. Aaron Margolis, a data scientist in Virginia, explained it to the New York Times this way: “What it gives you is kind of like an Aaron Sorkin movie. Parts of it will be true, and parts will not be true.” It all depends on what assumptions ChatGPT makes as it pulls together words.

Other times, the result can be completely false, and confidently so. One user asked ChatGPT: “What is the fastest marine mammal?” and the bot answered, “The fastest marine mammal is the peregrine falcon.”

“Incorrect information could be devastating in the context of pastoral care.”

Programmers call these mistakes “hallucinations.” Although problematic for a science project on marine life, incorrect information could be devastating in the context of pastoral care. Pastoral care responses must be sensitive and theologically sound. They also must be governed by larger therapeutic and spiritual goals.

Without the ability to fathom consequences, any counseling AI offers will be lacking in true compassion, according to Stoddard. “Decision making, to be compassionate, to make judgments and not just pattern-making decisions, has to be against the horizon of genuine contingency and mortality.”

When asked to write a sermon, prayer or to “explain the gospel,” ChatGPT defaulted to a conservative theology and used masculine pronouns for God. The system is not making a theological judgment; it is simply creating content based on the material it accessed. Evangelical conservatives produce more online material for the chatbot to absorb and adapt.

“The system is more likely to generate material that is sexist, racist and reinforces heteronormativity.”

This is problematic for moderate and progressive pastors who want to generate content in line with their beliefs. Women, minorities and members of the LGBTQ community also are underrepresented online. This lack of representation then limits the content available to ChatGPT. As a result, the system is more likely to generate material that is sexist, racist and reinforces heteronormativity. For pastoral care AI to be effective, it would need to eliminate these biases and appear more empathetic.

Another drawback of ChatGPT that might indirectly affect pastoral care is its ability to generate massive amounts of content in a short period of time. These AI systems can create misleading information and outright propaganda faster than any human fact-checker can counter.

“You could program millions of these bots to appear like humans, having conversations designed to convince people of a particular point of view,” Margolis said. The potential for further division in an already divided nation is staggering. It certainly will pose a challenge for pastors already struggling to provide pastoral care to churches and families torn apart by highly partisan politics and rampant conspiracy theories.

More powerful models coming soon

This spring, OpenAI, the group behind ChatGPT, will release GPT-4, an AI system potentially 100 times more powerful than ChatGPT. According to New York Times technology correspondent Kevin Roose, “Everyone who has seen GPT-4 comes back like they’ve just seen the face of God.”

Trained on 500 times as much data as its predecessor, GPT-4 will feature many improvements, including a higher probability of matching the content it creates with the user’s intent. This should decrease prejudice and incorrect information in the material generated. Training AI systems with information from more diverse sources will help also, although what form that training will take is unclear.

On Jan. 23, 2022, Microsoft announced a $10 billion investment to “accelerate” Open AI’s research and provide new “AI-powered experiences” to its users.

Partnership or replacement?

Even with improvements, Thomas is not ready to hand pastoral care over to a chatbot.

“I think all such tools may become usable additions to our ministries, but I don’t have a strong confidence at this time that we’re going be able to AI chat our way into genuine empathetic conversations, relationships or personal growth,”he said.

Which is why, when it comes to pastoral care, the best approach is one of partnership, not replacement, Delio added. “We tend to think in an either/or framework: It’s either us or the robots. But this is about partnership, not replacement. It can be a symbiotic relationship — if we approach it that way.”

Computers can perform compassionate acts, but they do not feel compassion.

The human ability to form social relationships with one another reflects the imago Dei in us. Computers can perform compassionate acts, but they do not feel compassion.

“The imago Dei is the reason theologically why I would say ChatGPT is not going be able to replace human contact and pastoral care,” Thomas said. “As entertaining as AI can be in cinema and literature, our need is for one another, not a replacement for one another.”

He also believes humans are the only members of creation who can reflect on the past, the future and themselves. “I believe that ability is the breath of God, our great gift. We cannot think … for a minute we could recreate that divine breath which animates and illumines. Of all God’s people, I hope the pastors don’t forget the gift and seek another.”

Therefore, oversight by a human pastor for pastoral care is still necessary, Stoddard said. “If we’re using AI-assisted care, we can’t step away from maintaining the responsibility of that. To delegate care is to draw on the gift of algorithmic systems. Delegating in the sense of yet retaining responsibility, not using AI to avoid offering compassion. Instead seeing the opportunity to enhance our compassion.”

It seems certain that artificial intelligence will play an ever-increasing role in the future of the world. Therefore, like email, video projection and livestreaming, it will find its way into the church. What form this will take and what role it will play is something Christians should consider.

Individuals are increasingly cobbling together their spirituality from a variety of sources, so clergy have an obligation to make sure those sources are sound. When it comes to pastoral care, not using AI when it might be beneficial would be neglectful, as would deploying AI to do ministry without any supervision.

The most effective approach lies in a responsible application of artificial intelligence for those who find it helpful or in situations when direct pastoral care is not possible.

Kristen Thomason is a freelance writer with a background in media studies and production. She has worked with national and international religious organizations and for public television. Currently based in Scotland, she has organized worship arts at churches in Metro D.C. and Toronto. In addition to writing for Baptist News Global, Kristen blogs on matters of faith and social justice at viaexmachina.com.

Related articles:

(How) do you baptize a bot? | Opinion by David Ramsey

How The Jetsons and Westworld help us think about robots, personhood and faith | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

As Facebook evolves to Meta, what is the future of consciousness and control? | Analysis by Rick Pidcock