On Friday, Jan. 3, Richard Hays succumbed to his decade-long battle with cancer. He was 76. Richard was a devoted husband to Judy Cheek Hays and devoted father to their son Chris and daughter Sarah — all of whom are themselves accomplished professionals. One of his greatest joys in life was being a grandfather. Richard Hays loved his family.

A quick glance at the highlights of Hays’ biographic details shows he walked a well-trod path. He was raised in Oklahoma City, educated at Yale and Emory, held posts in New Testament at Yale and Duke, earned tenure (at Yale), named to a chair (at Duke), and became a divinity school dean (at Duke).

Besides training ministers for service in the church, he mentored a bevy of doctoral students, three of whom who are now Duke faculty. He wrote a dozen academic books and scads of articles, lectured widely, became a respected member of his academic disciplines’ two major professional societies.

He was an ordained Methodist minister, coached Little League, loved baseball, was an avid Duke basketball fan.

While excelling every step of the way, Hays’ life and professional career were similar to that of others. Any difference was in degree, not kind. Or so it appears at first. A more attentive reading, however, reveals his life and work to be anything but ordinary.

Hays was marked by an uncommon collection of virtues.

He was patient. In my 35 years of friendship with him, I never once saw him lose his temper. Not once. This does not mean Hays did not have decisive views or hold to them without wavering. He did. He was just not easily provoked.

He was kind and gentle. I have watched him many times field a question whose answer was already made obvious by what he had just said and, with kindness, he would answer it again. He was invariably soft-spoken, except at certain moments at Cameron Indoor.

He was quiet, even a bit shy, in public; but in private he was a well-practiced conversationalist, especially when prompted by a good Pinot Noir or some highland irrigation.

But above all, Richard Hays was thoughtful. He was thoughtful and careful, for he believed words matter much. His thoughtfulness and care with words led him to let his writing do much of his talking. And write he did. Slowly. Painfully slow — and I now speak as editor for three of his books. He was as patient in his scholarship as he was with others. He walked at his own pace, as his inner strength and respect of language allowed him not rush his writing.

I first saw drafts of Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels some 10 years before those drafts became realized in a book. That he was writing a sequal to Echoes of Scripture in Letters of Paul was the worst-kept secret in publishing. I was understandably thrilled to have a look at his manuscript. It was overwritten, meandering genius. It was like peering into the studio of great painter, looking at the first sketches of the next work of art.

I pushed him when I first read them to forge ahead, finish the book. He smiled at me as we walked along on a Princeton sidewalk on a bitterly cold morning. He put his hand on my shoulder. “Carey, do you think the reconstruction of a historical Jesus matters to a New Testament theology?” While I thought a reconstructed Jesus both did and didn’t matter, what I had was an answer to my insistence. His polite change of subject revealed he had no intention of finishing the book any time soon.

Richard did not so much write as he did brood. He brooded and brooded — and he also brooded alone. When Reading Backwards was near completion, I offered to fly to Durham, spend a long weekend, working nonstop, to help him finish the book. After a long pause, Richard said slowly and softly, and in his most polite ‘stay out of my kitchen,’ voice, “Carey, No. I work better alone.” Writing for him was a solitary act, a part of his soul craft, as Richard was a poet.

“Hays wrote not one, or even two, but four field-changing books.”

For someone who was quiet, shy, even reclusive, Hays had impact, an outsized impact at that. Most scholars dream of writing one field-changing book. Hays wrote not one, or even two, but four field-changing books. So remarkable was his impact that Christianity Today named his Moral Vison of the New Testament one of the 100 most important books religious books of the 20th century — and the irony was Moral Vision was not even his best book.

At this point, readers of BNG may be wondering what Athens has to do with Jerusalem, what Richard Hays, a Methodist minister, biblical critic and seminary dean has to do with Baptists, what Durham has to do with Waco. The answer is, “quite a lot,” as it turns out.

In the last 30 years, Baptists have flocked to Duke for their theological formation, ministerial training, and to earn their academic credentials. Baptists who are Duke Divinity School graduates are serving in many a Baptist church, and Baptists who are Duke Divinity School graduates are teaching in many a Baptist college or university. It might be fairly argued that Duke Divinity School has been the best Baptist seminary there is.

The reason Durham became a Baptist Jeruslaem, it might be suspected, is that students went to Duke to study with ethicist Stanley Hauerwas. And they did. It is hard to underestimate the influence of Hauerwas on a whole generation of Baptists. And it might be suspected that students went to Duke to study with historian and theologian Curtis Freeman, director of the Baptist House at Duke and the most important Baptist theologian alive. And they did.

But the truth is this: Baptists went to Duke because of Hays. And even if they went there to study with someone else, Baptists fought their way into Hays’ New Testament classes. Hays had as much to do with forming biblical sensibilities among Baptists as anyone. As many stars as there were at Duke Divinity, and there were many, Hays was the brightest in the galaxy. While Duke basketball had its Mike Krzyzewski, Duke Divinity School had its Richard Hays.

It would be foolhardy to attempt to catalog all the ways Hays’ ideas have influenced Baptists. I will here point to three. But I do so with this one caveat: no summary like what follows is a substitute for reading Hays in his own words. Fortune favors those exercise their own patience with his writing by reading, slowly and carefully.

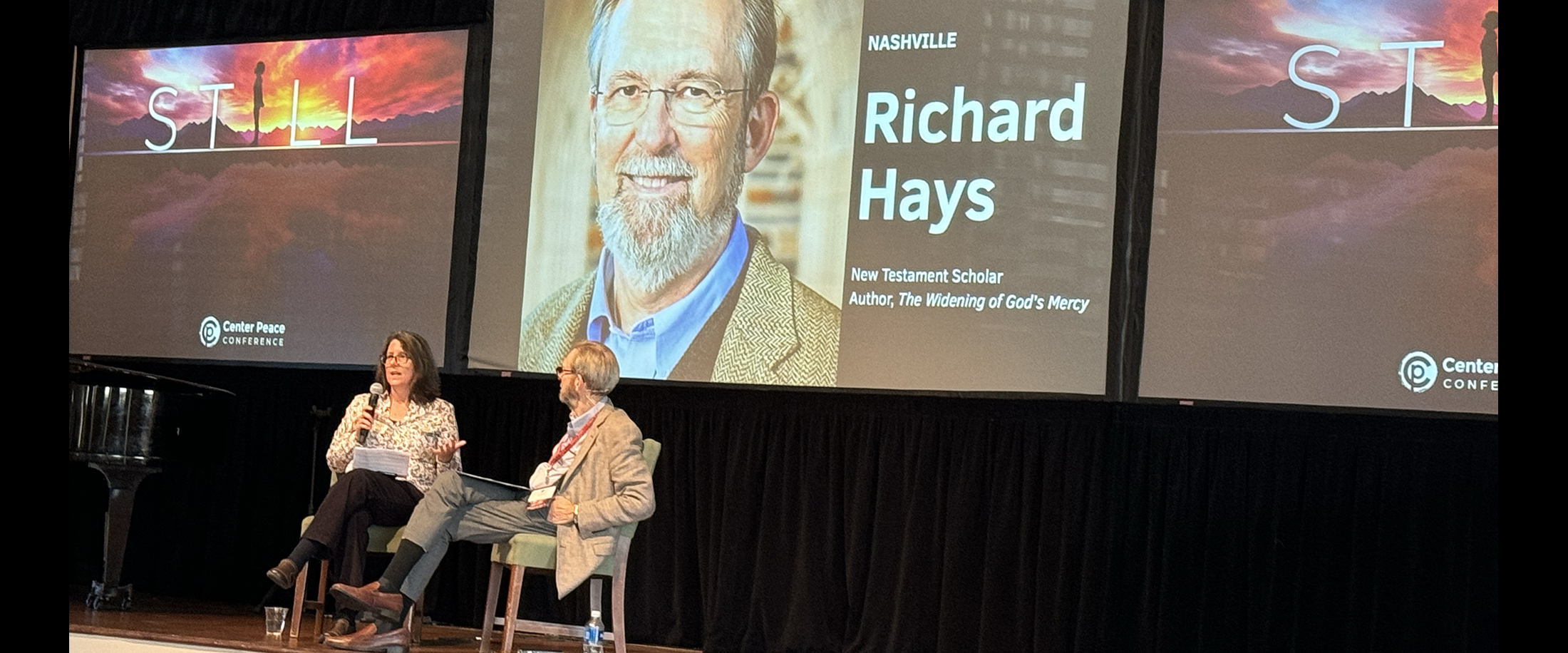

Karen Keen with Richard Hays at his last public appearance at the CenterPeace conference in Dallas in November 2024. (BNG photo by Mark Wingfield)

Faith of Jesus

Justification by faith has been heralded as the bedrock of Christian faith and the center of the biblical message. Baptists have not been alone in taking the justification of the individual as central. But Baptists, owing to their revivalist roots and frontier individualism, took it a step further by elevating the act of believing to sacramental status. For Baptists, there is nothing more sacred than the altar call, not even baptism or the Lord’s Supper. Baptists believe in believing, because Baptists believe that believing is the only necessary and sufficient means of salvation.

“Most dissertations both begin and end in extreme obscurity. But not Hays’.”

Richard Hay’s doctoral dissertation The Faith of Jesus Christ brings balance to the Baptist lopsided placement of faith in faith alone. Yes, a doctoral dissertation. Most dissertations both begin and end in extreme obscurity. But not Hays’. Although narrow in scope and weighed down by methodology, his dissertation, published in a dissertation series, became one of the most read, cited, discussed, used and influential dissertations ever composed, so much the so that it was republished in a second edition.

In it Hays asked two interesting questions about the central section of Paul’s letter to the Galatians. Hays wanted to know what it was Paul believed to be true before he ever composed Galatians and he wanted to know if Paul refered to what he believed to be true before he wrote the letter.

What Hays discovered was as surprising as it was revolutionary. There was, in fact, something “behind” or “underneath” Galatians. But this “substructure” of Galatians was not a set of ordered faith statements (like the Apostles’ Creed) or a set of timeless propositions (like Calvin might espouse). What was behind and before Galatians was a story, a story about Jesus, a story about Jesus that narrated how God’s faithfulness came to expression in Jesus’ faithfulness. Paul, according to Hays, was thinking through the implications of this narrative to craft pastoral advaice to troubled church, and the result of this exercise was Galatians.

Second, and importantly, Paul did in fact refer to this narrative about the faithfulness of Jesus in the phrase pistis christou. Most English Bibles, influenced by the Reformation, render this bit of Greek as “faith in Christ,” doubling down on the role of an individual’s faith in justification. But that is only one way to render the Greek phrase. And Hays’ patience and poetic insight led him to see the phrase was shorthand code for the narrative that constituted Paul’s Gospel. The phrase should not be rendered “faith in Christ” but as “faith(fulness) of Christ.”

To put it bluntly: Hays troubles the Baptist penchant for “belief in believing” by showing faith is always anchored by what God did in Christ. Indeed, what God did in Christ gives rise to the act of human believing. The object of believing isn’t belief (or shouldn’t be). Believers believe in something, and that something is the faithfulness of Jesus. Hays shows Baptists a third way, saving them from having to send their faith off to a set of decrees decided upon before time began or from having to trust themselves and in their own act of believing. Baptists, as Hays shows, can anchor their faith in the God who raises the dead and in a Jesus who answered the call of that God with a life of faithfulness.

Echoes of Scripture

Hays used what he had learned from his study of literature to read the Bible. His study of literature convinced him the Bible should not be dissected into its parts but should be read as a whole, and on its own terms, seeking what constitutes the Bible’s own affinity for itself.

“Hays shows that the New Testament drinks from the fire hose of the Old.”

In three of his books, Hays with care and patience follows along with the Bible tracing how the Bible forges itself as a whole. Hays pays special attention to the way the New Testament echoes the Old, creating a brand new figure in doing so. The New Testment’s asounding and jawdropping message about Jesus was crafted in light of an ongoing conversation with the Old Testment. The Old Testment, according to Hays, was a vast reservoir of stories and images, so vast and so powerful and so insistent that the New Testment could not help but express this new message in the language of the Old. Hays shows that the New Testament drinks from the fire hose of the Old.

Here again Hays has something to say to Baptists. Baptists have never known what to do with the Old Testament. One strategy is to turn it into one big, long Christological allegory. Jesus can, and should, be found in every story, on every page, behind, under and even in every rock. The Old Testament is really just Jesus in disguise. A second strategy has been to turn all the Old Testament into predictive prophecy. All the Old Testament is blueprints for the life of Jesus and his Second Coming. Aside from some poignant memory verses, Baptists steer clear of much of the Old Testament.

Hays shows that Baptist prizing and prioritizing of the Bible is on the right track. But he pushes further. Hays urges a full immersion into the world of the Bible and then the cultivation and curation of a Bible-forged competency to overhear how the Bible talks to itself. The Bible is no less than one book that the one God who speaks through.

Peace and mercy

Hays died with unfinished business. His Moral Vision of the New Testament put peace and peacemaking front and center. He even shows how the book of Revelaion, a book funded by a rhetoric of violence, is really about the peace Jesus wins through his suffering and death. But Moral Vision also contained Hays’ frank, honest and pointed reading of Paul’s comments about same-sex relations in the book of Romans.

Conservative Baptists were not alone in (mis)using what Hays had written as a blugdon to demonize, condem and then deny. I remember well the first time Richard spoke of his growing sense of regret about how he had been read and his desire to address this, and even to correct the record. His lastest and last book, The Widening of God’s Mercy, co-authored with his son Chris (himself an accomplished Old Testament scholar), is just that. In the book, Hays and Hays take a step back to look at the full sweep of the biblical record to address the complicated issue of human sexuality. Their conclusion is the Bible reveals how God has changed his mind and that the church is in the process of changing its positon, given its experiences with God.

Some will hail this as a bold and courageous position, while others will condem it, seeing in it just someone else who finally caved to the pressures of the left. Time will tell. It is still too early in the book’s life to pass judgment. But I see the book from a different vantage. I don’t read it as the lastest skirmish in some culture war. I rather see in it the same patient, careful, sensitive and compassionate mind I have seen in Richard’s other books. I see the book as an expression of God’s mercy and peacemaking.

We talked last Monday by phone. His voice may have been weak, but his spirit was strong. We exchanged goodbyes and laughed a bit. I had heard Judy often tease by saying she married someone who was going to be a biblical scholar or a Paul McCartney. I thought it all fun and games until one magical night a Les Paul was placed in Richard’s hands, and he began to play. Right before my eyes, Richard became 17 years old, a Paul McCartney “Rooftop Concert” doppelganger. Creativity, energy, imagination flowed from him. A fire hose had been turned on.

The same Richard who had the soul of a poet, the mind of a scholar, the imagination of a theologia and the heart of a preacher also had the right stuff to be the front for a band. Richard patiently waited for his chance. May he now sing and play with reckless abandon.

Carey C. Newman is a New Testamant scholar who serves as executive editor at Fortress Press. He lives in Waco, Texas.

Related articles:

‘When you’re wrong, confess and seek forgiveness,’ Richard Hays says

An oft-quoted biblical scholar changes his mind on LGBTQ inclusion in the church | Opinion by Anna Sieges

How Richard Hays changed his mind | Opinion by Alan Bean