Less than a month after John F. Kennedy was buried in Arlington National Cemetery and the eternal flame was lit, it was extinguished. A group of Catholic schoolchildren visiting the memorial was blessing the site with holy water and managed to douse the “eternal” flame.

It wasn’t the first time, nor has it been the last time Christians with holy water have tried to put out a bright light. March 9, 1994, comes to mind.

It was a cold, misty and blustery day in Fort Worth, Texas, which, in hindsight seems like the perfect setting for what transpired at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. Fundamentalist trustees controlling the seminary’s board fired Russell H. Dilday from his post as president.

For years, Dilday had confounded the ever-growing presence of right-wing trustees who came to board meetings with marching orders from radical denominational politicians determined to scorch and burn everything in their path. Russell Dilday presented a conundrum because of his well-known biblical conservatism. Calling Dilday a liberal would have revealed the truth, that their motives were political and not theological.

The difference, voiced as only Dilday could, was found in his oft-repeated line, “I’m conservative too. I’m just not mad about it.”

“I’m conservative too. I’m just not mad about it.”

While he “vigorously” opposed the assault on the Southern Baptist Convention and Southwestern Seminary, Dilday was clear in saying he was “not against conservative theology or unsympathetic with the desire to keep our Baptist denomination rooted in orthodox biblical faith. My disagreement was always aimed at the fundamentalist spirit, the secular political methodology of the takeover party.”

Therein was the problem. Or as one trustee, trying to justify differences with Dilday, blurted out, “He’s just not one of us.”

Time after time, meeting after meeting, I listened to trustees express exasperation with Dilday because he was smarter than they were. When they took his computer and changed the locks on his office, it was because they were intimidated by his ability to use one.

It was that kind of darkness, driven by meanness and ignorance, that led to what was a foreseeable outcome. Frustrated because they had no justification to fire him, trustees finally just did it, as one board member said, “Because we can.”

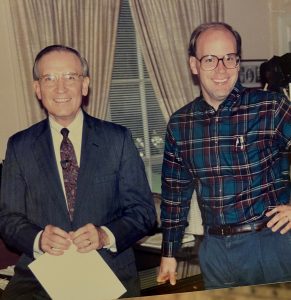

Russell Dilday and Scott Collins, 1989.

Over the years since, Dilday and I, along with his nephew Russ Dilday, would have lunch regularly. Inevitably, after catching up with each other, the conversation would turn to the antics of those trustees. We would find ourselves laughing loudly, recalling some of the hard-to-believe things that were said and done years earlier. Honestly, it’s hard to think a board of trustees like that ever existed.

When I was writing the obituary for my friend, I reached out to Baptist historian Alan Lefever for a quote. His reply was spot-on: “The grace with which Dr. Dilday handled his firing amazes me to this day. There was no desire for revenge, no bitterness at being unjustly dismissed, only a conviction to follow God’s call.”

Through it all, he never lost his dignity. But just as critical, he never lost his wit and sense of humor. That gift, along with God’s grace, gave him the ability to move on, even though the scars remained. He was always a light, brightening any encounter.

I’ve often thought if Rembrandt had used a computer to paint a portrait, Russell Dilday would have been the perfect subject. Often referred to as the last Renaissance artist, Rembrandt would gently spill just the right amount of light on the protagonist of his paintings, leaving the surroundings in the shadows.

Often surrounded by darkness, Dilday stood out as a bright light, a reminder that darkness does not like the light.

For the past 29 years, I have worn my own scars. As director of public relations at Southwestern Seminary that day, board leaders called upon me immediately after the firing. Slumped into a sagging sofa, Dallas attorney Ralph Pulley reached into a folder and pulled out several memos and “news” releases he had prepared, handing them to me. I was confused at first because the documents contained three different versions of what had transpired. It turns out Pulley had written them all because he didn’t know how Dilday would respond.

Later, reading through those documents, I realized Pulley had dated them March 8, the day before the firing, while claiming publicly on March 9 that none of the events had been pre-planned.

“The truth is, I was fueled more by anger and disgust.”

John Earl Seelig, my old boss, was brought back in by trustees to keep an eye on me, and in the days that followed I was watched closely. When my wife and I put a for sale sign in front of our house three weeks after the firing, I was asked why. When I had a conversation with Jim Denison, pastor of First Baptist Church of Midland, and Presnall Wood and Toby Druin from the Baptist Standard, I was accused of plotting to put Dilday back in the presidency.

I resigned less than three months after March 9 and started what has now been a 29-year journey at nonprofit Buckner International. My leaving helped me form an even closer bond with Betty and Russell Dilday. Betty would often comment on how much she admired my courage to leave.

I wish it had been courage. The truth is, I was fueled more by anger and disgust.

Through the years of spending time with Dilday, I realized how angry and unforgiving I had become. He was the epitome of grace and a Christlike example of responding to false accusations. I’m a work in progress.

There is a story often told around Seminary Hill back in the day about Isom Reynolds, the uncle of the late William Reynolds, who taught in the School of Church Music at the seminary. It seems Isom, who also taught church music at the seminary in its early days, had lost two fingers on his right hand when he was a child. When he would conduct music, he did so with only his thumb, index and middle fingers visible.

The result was a generation of Southern Baptist music ministers who conducted music the same way, thinking that’s the way it was done.

There are generations of Southwesterners alive today conducting their ministries with grace, courage, dignity and a kingdom focus because they watched Russell Dilday do it that way. It is up to us to keep the light burning.

As for that eternal flame at JFK’s gravesite, one of the grave guards standing nearby happened to be a smoker and used his cigarette lighter to immediately reignite the flame.

Scott Collins serves as senior vice president of communications at Buckner International. He served previously as director of public relations at Southwestern Seminary.

Related article:

Russell Dilday, Baptist statesman