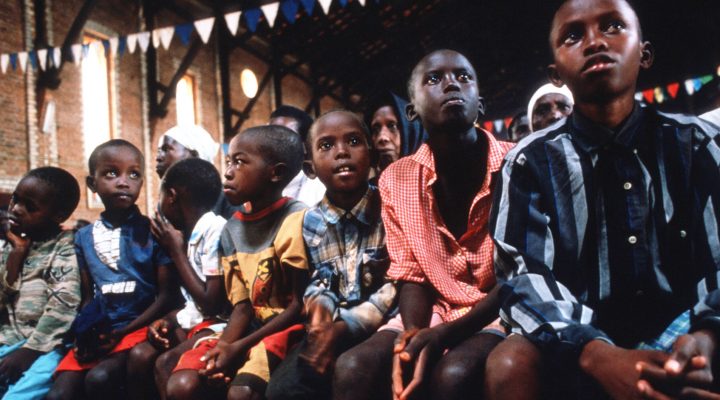

“People have managed to turn the page and move forward from grieving, from crying, and people have decided to live on, and people have been ready, have been willing to do the most difficult thing: to forgive. Well, but we can’t forget.”

These words were spoken by Rwandan President Paul Kagame at an event marking this year’s anniversary of what has generally come to be known as the Rwandan Genocide. The event, with the theme: ‘Kwibuka 29: Remember-unite-renew,’ was marked April 7 in Kigali, capital of Rwanda.

That date in 1994 was when the 100 days of killings began.

Background to a massacre

In 1994, a Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) rebel walks by the the site of an April 6 plane crash that killed Rwanda’s President Juvenal Habyarimana in Kigali, Rwanda. (AP Photo/Jean-Marc Bouju, File)

The tragedy unfolded after a plane carrying Juvénal Habyarimana, the Rwandan president of Hutu origin, and Cyprien Ntaryamira, president of Burundi, was shot down April 6 by a missile near Kigali International Airport by a person or persons still unknown.

Habyarimana’s government had battled a rebellion by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (known as the RPF), led mainly by the Tutsi ethnic group — one of Rwanda’s three ethnic groups.

The death of Habyarimana exacerbated tensions in the country and soon led to a reprisal by the Hutus against Tutsis and moderate Hutus. According to the United Nations, an estimated 1 million people lost their lives in the pogrom.

Some historians and analysts believe the tragedy could have been averted if foreign organizations like the U.N. and countries of influence had heeded warnings about inter-ethnic rivalry and animosity in the country.

Warning signs missed

One of those who hold this view is Jean Varret, a Frenchman deployed to serve as chief of military cooperation in Rwanda between 1990 and 1993.

Jean Varret

During his term of service in Rwanda, Varret was asked to chair a reunion of gendarmes who wanted to help in military cooperation. During the meeting, the chief of police told him he needed machine guns and artillery, he recalled in a France24 documentary interview. Varret said he was astonished by the request but declined it while telling the police chief policemen should rather be supplied teargas and not machine guns.

“He told me, ‘Look we are all military people here. I’m a colonel, you’re a general, let’s speak frankly. I need this equipment for my men because we are going to join the fight against the Tutsis.’ So, I asked him what he meant, and he said, ‘Well, you know, we are going to eliminate them. There aren’t many of them. It will be over quickly.’ I told him, ‘Do you realize what you are saying?’ He said, ‘Yes, but that’s how it is in our country. Tutsis are a danger. We are going to eliminate them.’”

“I really think that the French policy at that time was to let Hutus think that France would turn a blind eye should there be a massacre.”

Gen. Varret relayed his fears to his superiors in France, but they took no notice and did nothing to avert the danger, he said. France continued to associate with and support the Hutu leadership.

“I really think that the French policy at that time was to let Hutus think that France would turn a blind eye should there be a massacre,” he said.

Human remains on display at the Nyamata Church Genocide Memorial where between the 14th and 16th April, 1994, approximately 5,000 Tutsis were killed inside Nyamata Church on June 22, 2022. (Photo by Chris Jackson – Pool/Getty Images)

The world failed

Kagame, at the April 7 program, said the world failed Rwanda.

“Remember, at a time of need, when we needed every help we could get, everybody, the world, turned their back on us. The message is: You’re on your own. So, we should learn to be on our own, and I think we have learned enough. Therefore, the most important lesson our country has learned is to transform challenges into opportunities, and also use so little to do a lot. There is nothing Rwandans cannot overcome through unity, hard work and perseverance.”

From the scars of that tragedy, he insisted, Rwanda has transformed itself through a new spirit of oneness.

“Unity, being together, is the foundation of everything we try to do. From the beginning, we understood the need to cultivate and preserve the spirit of oneness. To give us hope for a better future,” he said.

The president paid tribute to the sacrifice of survivors and those who lost their lives during the horror-filled 100 days and said what happened was selective massacre.

“Rwandans, I thank all of you for refusing to be defined by this tragic history.”

“People were just being targeted and killed for whom they were, and nobody chooses what to be in that sense,” he said. “Nobody chose to be what tribe, race, ethnic group. There are many (things) you can choose to be. … You can choose your religion, but you don’t choose to be the person to be targeted. … Even those who targeted them have not chosen to belong to that ethnic group or things like that. It’s very clear that the wounds are still deep, but Rwandans, I thank all of you for refusing to be defined by this tragic history.”

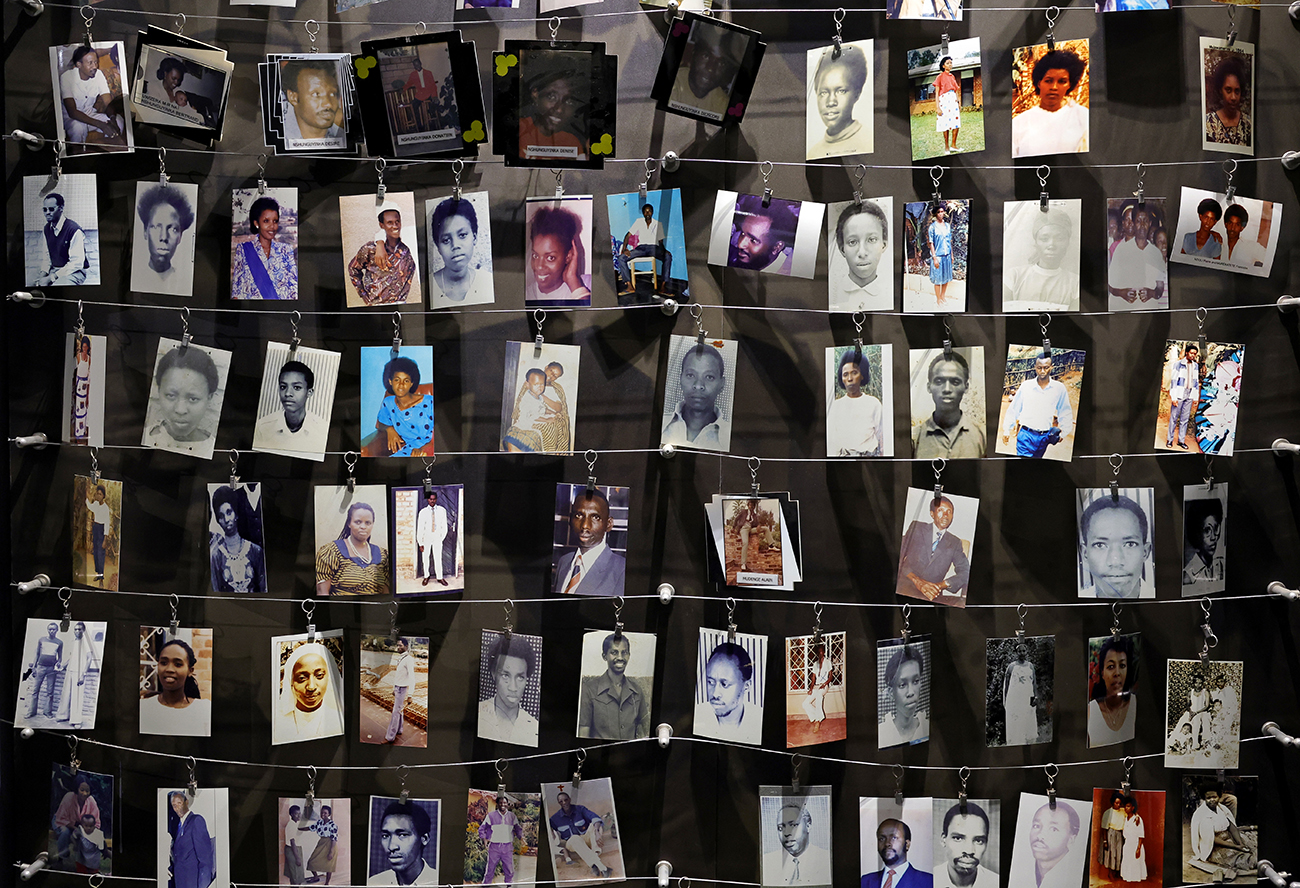

Photographs of victims on display at the Kigali Memorial for Victims of the 1994 Rwandan genocide in Kigali, Rwanda. (Photo by Chris Jackson/Getty Images)

Modern worries in a bordering country

While Rwanda has since turned a page, Kagame warned the same cannot be said of those not too far from its borders. Democratic Republic of Congo, a neighboring country of Rwanda, is still plagued by a decades-old conflict Kagame’s government has been accused of promoting, a charge the government denies.

“We cannot ignore the fact that things like violence and hate speech persist not so far away from here,” the president said. “Much as that’s so, we can also see the same indifference today as we saw in 1994. Genocide denial is a dangerous and deliberate attempt to block the truth. We must fight revisionist ideologies because they are easily passed on from generation to generation. We must fight denial because that is how history repeats itself.”

At a separate event in Ethiopia marking the anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, Moussa Faki Mahamat, African Union Commission chairperson, also raised concern about hate speech and militia gangs and the danger they pose to society.

“Here and there on our continent, armed militias are being formed on the basis of ethnic community, weapons of war are circulating and, more seriously, hate speech and the stigmatization of communities are being abundantly relayed and amplified by powerful social networks,” he said. “War crimes and crimes against humanity are being perpetrated. There is a risk that the irreparable can again be committed.”

The anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, he continued, “is an opportunity to draw the attention of African states to the magnitude of the threat as well as to our imperative obligation to oppose the self-destruction to which all these criminal practices lead.”

Kagame called for educating young Rwandans about their country’s past.

“We need to encourage young Rwandans to learn about our past so that they can lead with historical clarity but also with the sense of responsibility and accountability,” he said. “That is the essence of kwibuka twiyubaka.”

Not a ‘Rwandan genocide’

Aimable Twahirwa, a Rwandan journalist, told Baptist News Global the cost of the Rwandan tragedy was huge and certain things need to be corrected about what happened.

Aimable Twahirwa

“First of all, … this is not a ‘Rwandan genocide’ but a genocide against Tutsis in Rwanda. And this is not an ‘incident’ because it was well planned and executed by the former regime well before 1994. Second, the official figures of genocide victims is 1,070,014, mostly members of the Tutsi community, according to the Rwandan Ministry of Local Administration.”

Twahirwa witnessed the war.

“I grew up in Rwanda. I was fortunate to have good parents and a great family but most of them were killed during the genocide because they were simply Tutsis. Those who came to destroy our home and loot our properties were neighbor Hutus and their kids that I knew very well and were attending the same class with, for example. But because they were Hutu, leaders and military of the former regime came to convince them that Tutsi families were ‘cockroaches’ and ‘snakes’ to be killed and this was a way to dehumanize them because the former regime related Tutsis to the former rebel group and current ruling Rwanda Patriotic Front.”

Social differences between the Hutu and the Tutsi traditionally were “profound,” he said, citing as evidence the system of patron-client ties (buhake, or “cattle contract”) through which the Tutsi, with a strong pastoralist tradition, gained social, economic and political ascendancy over the Hutu, who were primarily agriculturalists.

Still, identification as either Tutsi or Hutu was “fluid,” he said, adding that while physical appearance may differ (the Tutsi were generally presumed to be light-skinned and tall, the Hutu dark-skinned and short), the difference between the two groups was not always immediately apparent, because of intermarriage and the use of a common language.

The seeds of the eventual genocide were planted well before Rwanda’s independence from Belgium in July 1962, he explained. “Students were denied the chance to pursue their studies, and some people were fired from public services and other administration because they were merely Tutsis.”

These attitudes no longer are tolerated in Rwanda, he said. “The lesson learned is that never again should anybody be discriminated against at school or killed because of his/her ethnicity or affiliation like religion or politics. People are being given equal chances based on their competences, which is not the case like it was during the genocidaire regime.”

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian-born freelance journalist who lives in Houston. He covers Africa for BNG.

Related articles:

Rwandan peacemaker given human rights award

Hopes of peace dim in Congo as rebel fighters once again take up arms against the government

Oral history archive explores relationship between faith and forced migration