Thirty years ago this month, hell’s gate flung open in the land of a thousand hills, leading to the loss of 1 million lives in Rwanda.

That poetic language by one analyst describes the most barbaric genocide the world has seen since the Holocaust.

While some eyewitnesses suggest there was a calculated buildup to the massacre — given the ethnic mistrust and animosity that had long prevailed between the country’s two major ethnic groups, the Tutsi and the Hutu — not even the most sinister pessimist could have foretold the tragedy that unfolded in the East African country from April 7 to July 19, 1994.

A plane crash

A Rwanda Patriotic Front rebel walks on May 23, 1994, by the plane wreckage in Kigali in which Rwanda’s late President Juvenal Habyarimana died on April 6. (AP Photo/Jean-Marc Bouju,).

The genocide was sparked after Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana and Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira were killed when their plane was shot down two days after signing a peace accord with a rebel group called the Rwanda Patriotic Front that had been battling the government.

The next day, April 7, violence spread from the capital city of Kigali, when members of the majority Hutu tribe — who held important positions in government — encouraged targeting and killing people from the minority Tutsi tribe. The massacre soon spread like wildfire across the country, and even moderate Hutus and people of the Twa ethnic group were not spared by the murderous mobs.

Foreign influences and ambivelence

While ethnic rivalry and animosity fueled the massacre, there also was a foreign link. That is the story of a documentary by Samuel Ishimwe, a Rwandan-born filmmaker whose parents were killed during the genocide, that premiered this month on the German station Deutsche Welle. Colonial Roots of the Genocide in Rwanda shows the role of Western countries including Germany and Belgium in Rwanda’s early history of segregation that contributed to the killings.

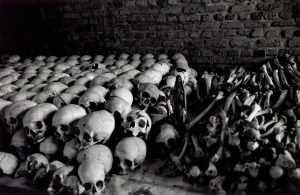

A row of human skulls and remains cover the interior of the Ntarama church which was destroyed during the genocide in Rwanda, Kigali, circa 1994. (Photo by Lane Montgomery/Getty Images)

The film features Lt. Gen. Romeo Dallaire, head of the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Rwanda during the genocide. Dallaire first was deployed to Rwanda to help supervise a peace treaty between RPF forces and Habyarimana’s government to end the civil war.

Asked what his initial assessment and understanding of the conflict in Rwanda was, Dellaire replied: “I went to meet with the Interahamwe, which was the militia (comprised) of youth, because the killings were done by young people. The adults, the army didn’t do the killing. The gendarmerie didn’t do much of the killing. They were behind it but the killing was done by the youths, the Interahamwe with machetes. They’re the ones who were on all the checkpoints and so on. And they had been indoctrinated by the MRND and CDR parties, by the hardline parties to treat the Tutsis as cockroaches.”

“They had been indoctrinated by the MRND and CDR parties, by the hardline parties to treat the Tutsis as cockroaches.”

He continues: “So, one of the first things they did was turn human beings into insects. I said, ‘How is it possible that you could be doing what you are doing, the slaughtering, the killing?’ They said, ‘How can you come and accuse us. You white guys, you, the Europeans destroyed people and millions of Africans, including all the slavery that was going on. And you’ve done it for a century or two. So don’t come and tell us that we are savages and so on when you are the ones who actually initiated that type of destruction of human beings.’”

Senator Romeo Dallaire speaks about genocide and crimes against humanity at the National Press Theatre in Ottawa on Thursday, Dec. 12, 2013. (AP Photo/The Canadian Press, Patrick Doyle)

In January 1994, three months before the genocide, Dellaire dispatched cables to the UN headquarters informing of an impending plan by Hutu government officials to carry out a massacre of Tutsis. This was based on his knowledge of the situation and meeting with an informant through a “very, very important government politician.”

The letter revealed an arms buildup which the informant suspected to be for the extermination of Tutsis. The informant was willing to divulge the location of a major weapons cache, but Dellaire’s superiors downplayed the threat.

“There is no negating that I left with the firm conclusion that all human beings were not being treated equally,” Dellaire says. He wonders how the UN could have deployed 67,000 troops to Yugoslavia (which at the time was faced with conflict) and yet he couldn’t even keep the 450 with him in Rwanda or get all the troops he needed.

“They simply said, ‘We will see how it works out. And, if they kill each other, well, it’s simply tribalism anyway because it’s in Africa.’ That was a big argument. They used all this tribalism (sentiment), it will last a couple of weeks and they will kill a bunch of them, and then we will go in, we will throw some money in and then maybe things will be better.”

Remembering

It turned out to be a pogrom, and many Rwandans live with that memory today.

One of those is Peace Hilary, a Rwandan journalist. “I was in Rwanda during genocide against the Tutsi in 1994 and I am one of the survivors. I lost my father, my two brothers, my aunties, uncles and cousins killed by the militias and Interahamwe. I was 16 years,” she told Baptist News Global.

Every year, Rwandans commemorate the anniversary of the genocide while the United Nations observes the International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

The solemn event in Rwanda typically allows the country the opportunity to look back while going forward. At the 30th anniversary event this month in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, were Bill Clinton, who was president of the United States at the time the tragedy occurred; Cyril Ramaphosa, South Africa’s president; and Olusegun Obasanjo, former Nigerian president.

The dais at an event to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide. (President Paul Kagame via X)

Lessons ‘engraved in blood’

Paul Kagame, Rwanda’s current president, said Rwandans are “completely humbled by the magnitude of (their) loss,” and the lessons they learned are “engraved in blood.” He noted the tremendous progress of the country since then is evident and a result of the choices the people made together to resurrect their nation.

“The foundation of everything is unity. That was the first choice. To believe in the idea of a reunited Rwanda and live accordingly,” he said. “Today, our hearts are filled with grief and gratitude in equal measure. We remember our dead and are also grateful for what Rwanda has become. To the survivors among us, we are in your debt. We asked you to do the impossible by carrying the burden of reconciliation on your shoulders, and you continue to do so, you continue to do the impossible for our nation every single day and we thank you.”

Rwandans, he continued, cannot now afford to be indifferent to the root causes of genocide, even if it means standing alone. And in all the people have been through, he said, three broad lessons stand out.

Rwandan President Paul Kagame walks with others toward an event commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide. (Photo from Paul Kagame via X)

“First, only we as Rwandans and Africans can give full value to our lives. After all, we cannot ask others to value African lives more highly than we ourselves do. That is the root of our duty to preserve memory and tell our history as we lived it.”

The second lesson, he said, is never to wait for rescue or ask permission to do what is right to protect people. That’s why Rwanda participates proudly in peacekeeping operations today and also extends assistance to African brothers and sisters when asked, he said.

The third lesson is to stand firm against the politics of ethnic populism in any form as “genocide is populism in its purified form because the causes are political,” he asserted.

‘Genocide Never Again’

Hilary, the journalist, said Rwandans’ commitment to learning from the past is palpable.

“When we say ‘Genocide Never Again,’ we Rwandans and the entire government officials mean it. That is why the government of Rwanda (initiated) reconciliation process among Rwandans. In the Rwanda Penal Code, genocide ideologies, genocide denials are punishable.”

The Africa Christian Professionals Forum on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the genocide, expressed its solidarity with Rwanda and commended the people’s resilience and determination in rebuilding, fostering reconciliation and offering hope to the country’s traumatized people.

Apart from any external influence contributing to the Rwandan genocide, questions have been asked about the role or failure of religious leaders in Rwanda to stop the conflict or save people from the blood hunters.

The church, for example, is seen as a sanctuary and sacred ground for many believers. Therefore, many Rwandans, in fear of their lives, took shelter there. But mobs at different locations invaded and desecrated holy grounds to snuff the life out of people. Worse, news emerged that some church members betrayed people they were supposed to protect, leading to their brutal deaths.

Reflecting on the genocide, ACPF acknowledged humanity witnessed unspeakable violence, resulting in countless innocent deaths.

“Today, we pause to reflect on the immense suffering endured by victims and their families, offering our deepest condolences to all affected,” it said. “As we mark this solemn anniversary, let us recommit to creating a world where such atrocities never recur. May the memories of the victims inspire us to tirelessly pursue peace, tolerance, and understanding.”

The body also called on the “international community to reaffirm its commitment to preventing genocide and mass atrocities, promoting justice, human rights and dignity for all.”

Related articles:

Rwanda: 29 years after the genocide, there are still lessons to learn

Alleged mastermind of Rwandan massacre inside church arrested 30 years later

Rwandan peacemaker given human rights award