Sometimes, pastors need a place to get away, a place to go where they can recharge between sermons and committee meetings and the like.

They need a sanctuary from the sanctuary — a space where they can delve into Scripture, pray or receive direction from a mentor or fellow pastor.

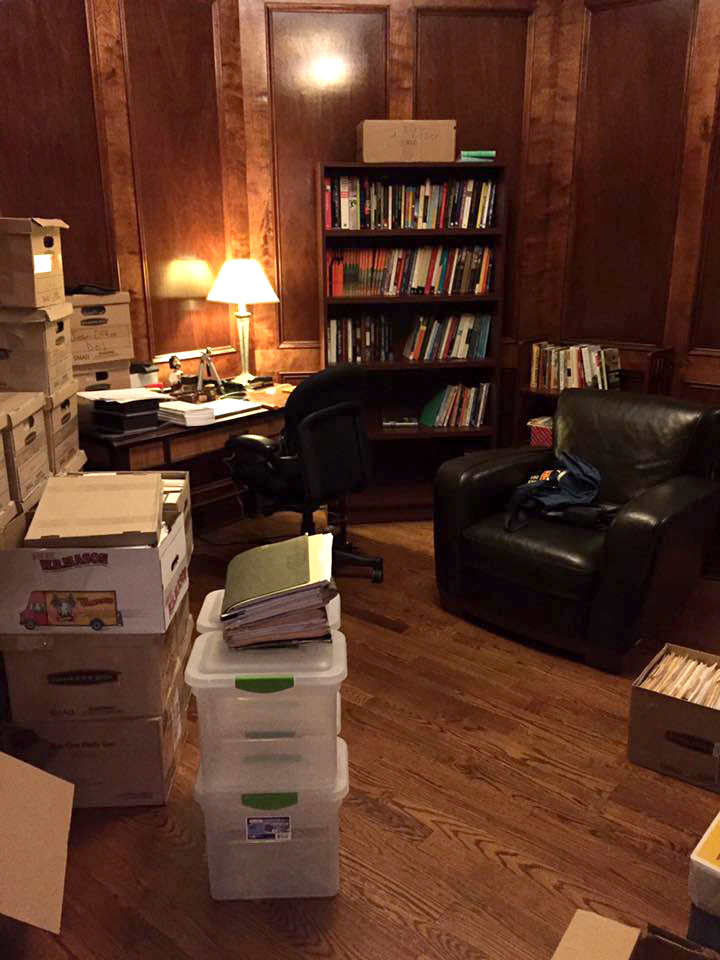

Jason Coker said his recent move from Connecticut to take the reigns of CBF Mississippi have left him feeling unsettled while his office remains remains unready. (Photo/Jason Coker/Facebook)

Jason Coker said he definitely needs such a space. Usually that means being in his office ringed by books.

“I am used to a desk. That’s my comfort zone.”

But Coker is out of the zone, for the moment. He has spent the last few weeks relocating his family from Connecticut to the Deep South, where he is taking the reins of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship of Mississippi.

Late last month, Coker posted a photo of his office, with some books on shelves, others in boxes and plastic bins. “Getting there slowly but surely,” his post said.

At the moment it’s more on the slowly side. Coker said the process has a few more weeks to go, which has left him feeling out-of-sorts — despite the fact he can do most of his work on his smartphone and laptop.

“I still need a dedicated space to be in,” he said. “Without that I feel undone.”

‘It’s about intimacy’

That feeling is a classic one for those separated from, and yearning for, sacred space, said Jaan Ferree, an Asheville, N.C.-based “intentional designer” with a specialty in designing sacred space.

What constitutes sacred space can vary widely, from church sanctuaries and prayer gardens to cozy home spaces to national battlefields. What binds them together, Ferree said, is the sense of safety and comfort they evoke.

“They are comfortable and offer freedom from clutter and from stimulation from the outside world,” she said.

Privately, sacred space can be created by using “invitations or symbols” such as photographs of loved ones, religious icons and images from nature, she said.

The presence of candles, lit or unlit, also evoke experiences of the sacred, Ferree said.

All of those elements are typically present in cathedrals, prayer labyrinths and battlefields like Gettysburg, she added. They are “prayer soaked” places that open visitors up to vulnerability, quiet and a more intimate relationship with God.

“It’s about intimacy,” Ferree said of sacred space. “It’s about one-on-one relationships.”

‘I feel very limited’

It’s also about slowing down and finding a balance between heart and mind, she said.

“Often in our culture we are bombarded with over-stimulation of the mind and we forget that it is important to find that balance,” Ferree said.

Sacred space offers a sanctuary from that bombardment by providing a quiet in which to connect with peace, she said.

And that can definitely happen in living rooms, dens and offices.

“There is that one-on-one relationship we have with God when we get in our chair with the lamp and our prayer book or our journal,” she said. “We are being still and we are listening.”

Being separated from that space, Coker said, has created somewhat of an “existential crisis” for him.

“Not having a desk and not having books on shelves, I feel very limited,” he said.

Finding a quiet place to read, pray, reflect and meditate effectively turns that space into a sacred one, experts say. (Photo/Brett Jordan/Creative Commons)

“I usually have books on selves and then I have books I am actually working [with] on my desk,” he said. “That’s been my practice for a decade or more.”

But Coker said he wonders if his longing for order is a generational one. He said he’s noticed that younger people don’t seem to have those needs.

Smartphones, laptops and other portable technology may be eliminating the need for sacred space as he has come to know it.

“Their sacred space is in their pocket and that’s their comfort zone,” Coker said.

“This might be the reason why churches don’t have membership anymore,” he added. “What feels comfortable to us, and like sacred space, doesn’t translate to the next generation where everything is available in any space.”