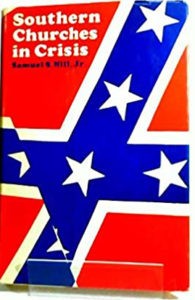

In his monumental work, Southern Churches in Crisis, published in 1966, Samuel S. Hill Jr, then chair of the religion department at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, wrote:

The cultural-social complex in which revivalism-fundamentalism came to birth and flourished daily undergoes significant modification. The passing of the old culture spells the decline of this culture-religion spawned in it and so closely tied to it. As a result, the last four or five years have witnessed the first trends in scores of years toward the stabilizing of religious statistics. Although the denominations do not yet acknowledge it or grasp its significance, an unprecedented era, likely to be marked by flux and decline, is breaking upon them. The heart of the matter is that the ministry of the churches is ever more irrelevant to persons in the new society. … If what the churches are doing does not relate the divine message, compassion, and power to (people’s) real lives, their understanding, their needs, and their problems, the churches act irresponsibly.

What Samuel Hill projected into the future 55 years ago has become our present. Perhaps a brief foray into his thought will provide insight into where Southern churches have been, in order to better understand where they are right now.

Bill Leonard

Church-folk often ask: “How did American churches get into this time of decline and division?” One response might be: Samuel Hill saw it coming.

Hill, “the dean of Southern religion studies,” died on June 1 in his 94th year. Asked to contribute to his obituary, I went immediately to Southern Churches in Crisis, a book that has shaped innumerable students of American and Southern religion. Although I never studied directly with Sam at any of the universities where he taught — Stetson, North Carolina, Florida — I joined the vast classroom of persons who benefited from his written scholarship. We met in the 1980s, and I remain grateful for his friendship. Sam’s writings not only instructed me in the study of religion in the American South, but also convinced me that it was a worthy endeavor, at once painful and enriching. His friendship helped me learn to love such studies even more.

Rereading Southern Churches in Crisis, I realized that while Sam’s focus was on the religio-social dilemma of the 1960s, the scenario that he sketched is coming to fruition in Southern churches (and elsewhere) in 2021.

By the way, if you don’t think Southern churches are “in crisis” right now, you’ve no need to read further. You obviously haven’t been reading Baptist News Global; or listening to social media, cable TV, talk radio or the U.S. Congress. If you do believe that there is a crisis in Southern churches (and throughout the U.S.), then perhaps Samuel Hill’s early analysis can provide some perspectives for confronting it, an analysis summarized in the quote that introduced this essay.

Consider these three points:

First, Hill recognized that Southern churches, particularly “Popular Protestantism,” had become lively sects that forged a rather cozy relationship with the South’s “cultural-social complex.” In so doing, they had become an organizational “establishment,” highly privileged in Southern society, yet retaining elements of their sectarian past including doctrinal uniformity, conversionist evangelism and condemnation of the very “worldliness” that their culture-favored status often provided.

First, Hill recognized that Southern churches, particularly “Popular Protestantism,” had become lively sects that forged a rather cozy relationship with the South’s “cultural-social complex.” In so doing, they had become an organizational “establishment,” highly privileged in Southern society, yet retaining elements of their sectarian past including doctrinal uniformity, conversionist evangelism and condemnation of the very “worldliness” that their culture-favored status often provided.

Hill predicted that “the passing of the old (Southern) culture” would bring a decline (I’d now say an end) to the “culture-religion” of Southern churches. In 2021, some churches and denominations, reduced numerically, have turned to government in order to retain that “culture-religion” relationship. At best, a temporary fix.

Paradoxically, many of those who blame secularism for destroying faith-based foundations of American culture often fail to recognize that, at least in the South, secular and religious elements merged for generations (slavery being a worst-case illustration), a tension that was bound to break apart.

Second, Hill understood that transitions in Southern culture impacted the evangelical identity of that “Popular Protestantism,” meaning Baptists, Methodists and other conversionist-oriented groups that dominated their environment. Revivalism, the calling of persons to Christian conversion through distinct religious experiences, Hill believed, already was waning as a primary vehicle for entrance into Christ and the church.

“What Hill described as a ‘trend’ in 1966 would become increasingly normative among many Southern and American evangelicals by 2021.”

In the South, however, such evangelistic zeal and conversion methodology often was linked to fundamentalism, involving “groups which are rationalistic in orientation” and intent on “elaborating and validating propositional revelation.” In other words, “propositional revelation” could turn heart-warming conversion into intellectualized transaction. What Hill described as a “trend” in 1966 would become increasingly normative among many Southern and American evangelicals by 2021.

Hill was particularly critical, not of the church’s call to vital religious experience of God’s grace, but to the increasingly propositional nature of conversion. His critique of traditional conversion processes included: (1) the belief that it would “rectify all individual and social ills, and by itself humanize life; (2) a tendency to “overlook persons and their needs unless they are ‘prospects’” for church membership; (3) a tendency to separate the conversion moment “from the rest of life.” Rather, Hill asserted that the church’s “direct objective is service. As a result, it forever runs the risk of adding few, or no, new members to church rolls.

Third, Southern Churches in Crisis links 1966 and 2021, when Hill writes: “The heart of the matter is that the ministry of the churches is ever more irrelevant to persons in the new society.” Sobering words, increasingly self-evident in the empty pews of 2021.

The response of Southern white churches on racial issues accounts for some of those departures, then and now. Hill declared: “In view of its record of reactionary and sub-Christian conduct toward Negroes, repudiation of the church will seem the only authentic reaction to those who perceive the massive corporate guilt which rests on the shoulders of the region’s Anglo-Saxon peoples.”

In 2021, the quest continues for an “authentic reaction” to race and racism inside and outside Southern congregations, as white-majority churches affirm that “all are one” in Christ Jesus, while weighing their response to Black-generated movements related to Black Lives Matter and Critical Race Theory.

“Critical Race Theory is not a plan of salvation. It is not competing with the gospel.”

Those tensions were evident in the annual convention sermon at the June meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention when the preacher noted that Critical Race Theory, positively acknowledged in a 2019 SBC resolution, had produced “the unusually rancorous debate,” involving many persons “speaking about something they have little understanding of.” Offering his own analysis, he asserted that Critical Race Theory is “a flawed diagnosis, a hopeless prognosis, and writes a powerless prescription rooted in materialistic humanism and political power.” He added: “It is powerless because it cannot cure the deepest ills of the human heart. It brings no transformation, produces no love, and results in no justice. It cannot produce what only the gospel can produce: A changed heart and a new humanity.”

Yet Critical Race Theory is not a plan of salvation. It is not competing with the gospel. Education Weekly explains: “Critical Race Theory is an academic concept that is more than 40 years old. The core idea is that racism is a social construct, and that it is not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something embedded in legal systems and policies.”

The gospel does indeed change hearts. I learned that from Jesus and folks like my earliest SBC Sunday school teachers.

But if we’d waited on the born-again Southern Baptist slaveowners to bring transformation, love and justice to their slaves, Black folks might still be in bondage. And that would be a real crisis.

I learned that from folks like Samuel S. Hill Jr. Rest in peace, Sam, and thanks.

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.