J. Alfred Smith Sr. is not happy with the six Southern Baptist Convention presidents, who recently issued a declaration against Critical Race Theory.

“They are more afraid of Critical Race Theory than the ugly racism that has our democracy about to be crucified with lies. They are complicit with evil. They don’t speak out against conspiracy theories. But they will make a big hullabaloo about Critical Race Theory,” said the veteran California Baptist pastor and denominational leader.

J. Alfred Smith Sr.

Smith served four decades as pastor of Allen Temple Baptist Church in Oakland, Calif., and earned a doctor of ministry degree at nearby Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, one of the six SBC seminaries. He is a member of the American Baptist Churches in the USA and dually aligned with the Progressive National Baptist Convention, where he served as the organization’s 12th president.

For many years, Smith participated in a partnership with Golden Gate Seminary and the then-Home Mission Board of the SBC training pastors and denominational leaders in urban ministry.

Now 89 and retired about an hour away from Oakland, Smith still reads widely and quotes biblical references from memory in rapid succession. He reads, he said, “to exercise the muscles of my mind.”

And from his vantage point, the SBC seminary presidents need to exercise the muscles of their minds a bit more too.

“I’m not going to be charitable,” he said. “They want to take passages of critical theory that are expressed by people like Cornel West when he spoke of Marx’s methodology to unmask evil and its oppression of people at the bottom. They say they are biblical and that’s why they can’t go with Critical Race Theory.

“But Amos, the eighth-century prophet, exposes the same thing. I don’t understand why they ignore the eighth-century prophets and ignore the Jesus of the Gospels,” he continued. “They are in bed with the Pauline transcendental Christ and not with the Christ who preached his first sermon from Isaiah 61.”

By that last point, he means there is theological peril by reading Paul apart from the Gospels.

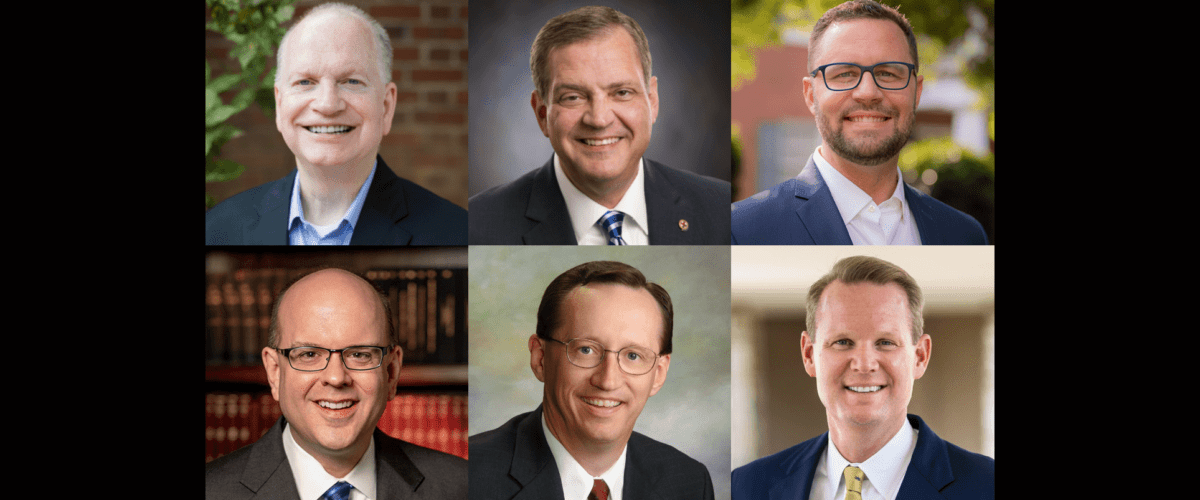

Stained glass of biblical scenes inside the Allen Temple Baptist Church sanctuary.

“If you just read Paul, you never would have known that Jesus was born poor in a manger and that he was born to an oppressed nation,” Smith explained. “That he was born as a Jew in oppressive Rome and that he was an immigrant in Egypt. The Jesus of Matthew 5, the Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount, the Jesus of Matthew 25. the closest that Paul gets to that kind of thinking — and it is still metaphysical and transcendental — is over in Philippians, when he talks about the kenosis that emptied himself and became a servant even unto death, the death of the cross. But most of Paul is a quibble with Judaism.”

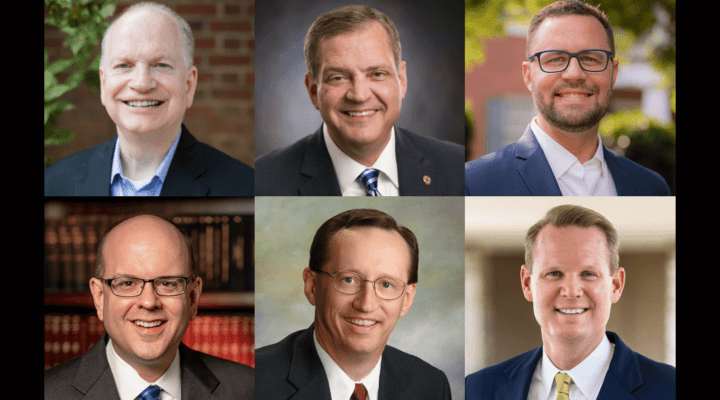

“The SBC seminary presidents” — all white men — “do not own the Christian story,” Smith asserted.

Instead, he suggested, Christians should celebrate those theological leaders who — unlike the SBC leaders — “are not captive to the structural logic of normalized white supremacy that preserves dehumanizing axiological systems that sacralize and legitimize racism in the theological academy.”

“Those who reject Black womanist and male theologians and pastors of liberation need to read again but for the first time the truth that early Christianity was in the middle East and North Africa,” he declared.

“The SBC seminary presidents do not own the Christian story.”

Smith cited theologian and author Esau McCaulley, who wrote in his book Reading While Black: “In the stories of Ephraim and Manasseh, we see that the promise of Abraham was first fulfilled by bringing two African boys into the people of God. We saw the inclusion of Africans again reiterated when a multiethnic group left Egypt.”

Christians and seminary leaders who want to truly understand Critical Race Theory ought to read another book, too, Smith said: With Liberty and Justice for Some: The Bible, the Constitution and Racism in America, by Susan Smith.

This one book, Smith believes, “would open the eyes of good-meaning white people who say they’re not prejudiced.”

Believing you’re not prejudiced is not the same thing as understanding prejudice and racism, he explained. “The average white layperson does not understand structural racism and how it’s in the grain of the wood so that they are socialized and even a person like myself has been socialized to accept the normality of white privilege.

“So many of the Southern Baptists talk about this from a cognitive point of view and it becomes theoretical and abstract, while I feel the pain of it because I have children and grandchildren and great grandchildren.

Images of Black leaders adorn stained-glass windows on one side of the sanctuary at Allen Temple.

“I have a great grandson who fights the same battle that I’m fighting,” the pastor said. “And we thought we were making progress under his dad, but racism went underground and then ‘Trump-vangelicalism’ made racism raise its ugly serpentine head and gave credibility to it.”

Despite the protestations of the six SBC seminary presidents, systemic racism is real and dangerous in America today, Smith said. “Systemic racism is racism that’s ingrained into the culture.

“Every Black father like myself has to pull his young son aside and explain to that boy how to act if he’s stopped by the police. No white man even thinks about that. They just assume the police officer is a friend to their son and if they get caught for doing something minor the police will put them in the car and drive them home. But if you’re Black, look out. What if you’re not brought home, if you don’t make it home alive?”

Smith learned these lessons from a young age, growing up in Kansas City, Mo., which he called a “Southern state with a Northern exposure.” He attended segregated schools there.

But in the summertime, when he was sent to visit family in Mississippi, he learned other lessons. “I would have to move to the back train, to the very last coach, when we crossed the Mason and Dixon Line.”

An Advent wreath inside the Allen Temple sanctuary.

And upon arrival in Mississippi, things got worse. “I remember waking up one morning in Mississippi to go to the store with my cousin in a place called Jonestown, Miss. While walking into the center of town with my cousin, there were older white men sitting in chairs in front of the store buildings. And one of them said to me, ‘Good morning, Little Nigger.’ I said, ‘My name is not Little Nigger. My name is James Smith.’ They said to me, ‘Boy, you’re not from around here are you?’”

In those days, the sidewalks were not made of concrete but of wooden planks. “When a white person came from the opposite direction, Black people had to get off the sidewalk until they passed. You weren’t allowed to look a white person in the eye. You had to look down.”

From a young age, he said, he knew “the meanness of Mississippi racism.”

And yet even as an esteemed pastor of a prominent church in the San Francisco Bay area, he continued to experience systemic racism years later.

“The Allen Temple Baptist Church was redlined when it came to buying insurance just because of where we lived, just because of our ZIP Code. We put up a beautiful sanctuary with stained glass windows. But no bank in the city of Oakland was lending money to Black churches. We had to deposit our money with them, and they were using our money for investments, yet we couldn’t borrow money from them to build the church. We had to borrow money from American Baptists. That’s structural racism.”

With no help from the local banks, the church built and installed a set of stained-glass windows with a unique perspective. On one side of the sanctuary is a set of windows depicting Black men and women pioneers. On the opposite side, a set of windows with images of biblical characters.

The baptistry at Allen Temple.

And above the baptismal pool, a hand-painted image of Philip baptizing a Black Ethiopian eunuch.

The church’s website quotes Smith as saying “the stained-glass windows serve as a teaching message of race pride — Black men and women who were committed to lifting up the race.” And in those windows, he said, “I especially want children to see the beauty of Black people who convey a message of hope in a hostile world.”

Today, reflecting on the denial of systemic racism by the SBC seminary presidents, Smith looks again to the windows. He sees there “Black images of women and men liberation leaders in the blood-soaked struggle against demonic racism.”

And then he concludes: “I am 89 years old. And I’m too old to bow down to President Mohler and his cohorts. I talk the way I talk because I want to die free.”

Related articles:

SBC seminary presidents are propagating fear to maintain control | Laura Levens

Is it time for Black Christians to give up on the SBC? | Corrie Shull

How I learned to name my oppression — and my privilege | Meredith Stone