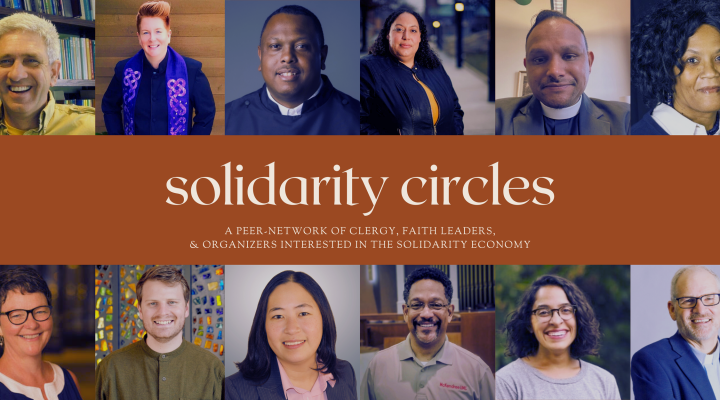

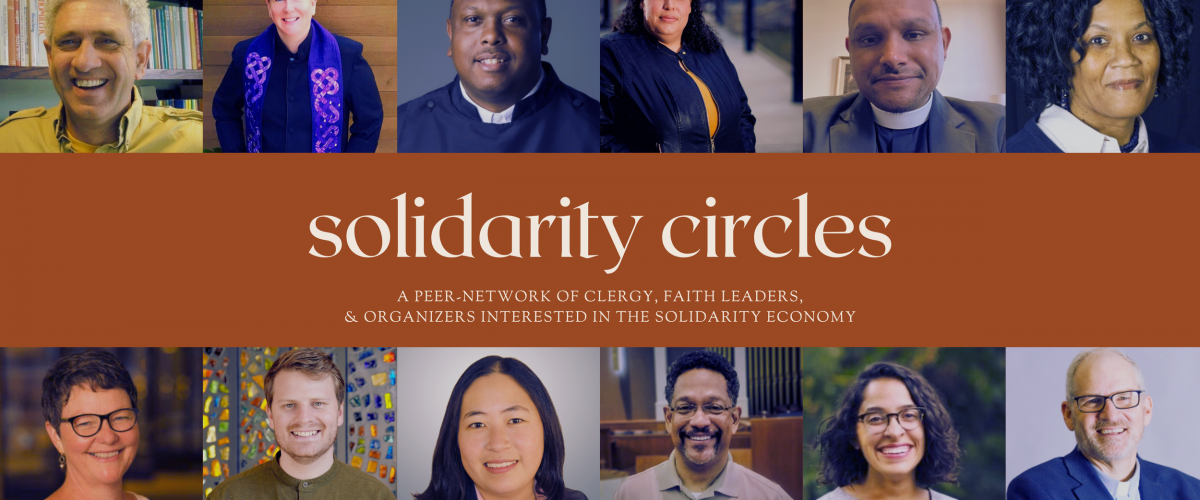

What if leaders from different walks of life committed themselves to finding ways to build more collaborative, fairer, more equitable economics? What if they worked together in a virtual peer-to-peer network to confront challenges and learn from one another’s experiences?

Those “what-ifs” come together in Solidarity Circles, offered by the Wendland-Cook Program in Religion and Justice at Vanderbilt University Divinity School in Nashville, Tenn.

Joerg Rieger

The Wendland-Cook Program is an interdisciplinary curriculum that focuses on justice issues “that arise at the intersection of religion, economics and ecology,” according to the divinity school website. A United Methodist scholar, Joerg Rieger, founded the program in 2019, and noted United Methodist author and benefactor Barbara Wendland of Temple, Texas, supports it.

Wendland-Cook aims “to develop resources and opportunities for students, scholars, clergy and activists to envision and create a more just and sustainable world for all,” the website explains.

In keeping with those overall objectives, Solidarity Circles rests on a global movement known as the Solidarity Economy that seeks “to build a just and sustainable economy where we prioritize people and the planet over endless profit and growth. Growing out of social movements in Latin America and the Global South, the solidarity economy provides real alternatives to capitalism, where communities govern themselves through participatory democracy, cooperative and public ownership, and a culture of solidarity and respect for the earth.”

Now in the third year, Solidarity Circles can be described as a “leadership” curriculum, but it’s more than traditional learning and leading methods, Aaron Stauffer, its director, said.

“We bring together clergy, faith leaders and organizers who find themselves hungry for communities of practice and learning,” Stauffer noted.

A survey showed clergy are “over-resourced” with Bible studies but lacked “communities of practice” that can “walk alongside them.”

In surveying about 100 pastors over two years, Stauffer and Rieger discovered clergy are “over-resourced” with Bible studies and theological resources, Stauffer said. But they lack “communities of practice” that can “walk alongside them” as they try to engage and energize their institutions.

At its core, Solidarity Circles offers “a laboratory for change-making,” Stauffer said.

Inclusion of businesspeople, labor organizers and nonprofit leaders in Solidarity Circles aims to spread its collaborative methods and results into society beyond the church and the academy, he said. Rather than hoard their knowledge as is prevalent in a capitalist model, Solidarity Circles participants are encouraged to share their experiences to benefit others and to engage in mutual ways of self-governance.

Larissa Romero

Larissa Romero, a member of Solidary Circles’ 2022 cohort, said she found her experience got her thinking specifically about the ways that class and economics can obstruct churches and faith groups from creating movements for needed change.

“A lot of church work is organizing systems of people to move forward in particular ways,” she explained. “Solidarity Circles looks at how it can be done healthily and collaboratively. We looked at the similarities between nonprofit or faith-based groups and labor groups and how they use similar ways to get organizations to move forward.”

Originally ordained in the Reformed Church in America and now serving a United Church of Christ congregation in Denver, Romero contrasted Solidarity Circles with seminary using a metaphor from Sarah Juist, a pastor and writer in west Michigan.

“Seminary is really like a culinary school where you learn how to make incredible meals, but then as a pastor, each day you’re trying to figure out what to make with the ingredients you have available,” Romero said. “Even if you have field work or clinical pastoral education in seminary, it still doesn’t train you in how organizations work.”

Solidarity Circles seeks to bring pastors together with “people who have failed similarly to you, but who have found solutions.”

In contrast, Solidarity Circles seeks to bring pastors together with “people who have failed similarly to you, but who have found solutions,” Romero said. “You learn from one another.”

Each Solidarity Circles group meets virtually once a month for 90 minutes. Conversations start with an assignment from Stauffer but always include discussions about members’ projects.

“You’re encouraged to come in with an idea for a project,” Romero said. “The Presbyterian congregation I was serving in Nashville at the time was going through a discernment about what to do with its historic building that was eating up resources. I was able to bring that project to the Solidarity Circle and ask what it would look like for the church to change.”

“Once you are in the rough-and-tumble of ministry, you begin asking different questions,” Stauffer said. “Those questions arise from doing the work as it exists now. The work of ministry looks different from even 10 years ago, so theological education has to be adaptive, and Solidarity Circles are adaptive. Each iteration is different from what came before.”

Aaron Stauffer

Topics that previous Solidarity Circles groups tackled include questions of business integrity, United Methodist disaffiliation issues, church decline and the contexts of participants’ working situations, Stauffer said. “It’s relational ministry, learning how deep and real the crises are.”

Solidary Circles provides an education in “how you use power,” Romero said.

“Seminary education can sometimes breed an attitude of savior-ism, as ‘I know best and I know how to handle the problem,'” Romero said. “Solidarity Circles explicitly focus on class and the ways in which you use power.”

She cited Jesus as her leadership model.

“Everything Jesus talks about, it doesn’t exist in a vacuum,” Romero said. “Jesus operates in the Roman empire, an occupied space. (In Solidarity Circles) you’re starting with that understanding of how we effectively live out our faith in a given situation. It’s not something talked about outside the charity model.”

Cynthia B. Astle is a veteran journalist who has covered the worldwide United Methodist Church at all levels for more than 30 years. She serves as editor of United Methodist Insight, an online journal she founded in 2011.

Related articles:

A church trial will be better for suspended bishop and the UMC

Texas megachurch relents, follows United Methodist rules to exit denomination