The specter of Critical Race Theory loomed large over the Southern Baptist Convention’s annual meeting June 15-16, yet no concrete actions to address it by name were taken.

That delighted Southern Baptist pastors and leaders who believe months of debate about this academic construct have distracted from the denomination’s missions and evangelism work. But it dismayed Southern Baptist hardliners who are certain Critical Race Theory is one of the greatest threats currently facing the nation and the denomination.

Tom Ascol

Tom Ascol, leader of the SBC Calvinist group called Founders Ministries, wrote in a blog on that organization’s website: “There were two types of Southern Baptists in the convention hall: those who wanted open discussion and opportunity to repudiate Critical Race Theory and intersectionality vs. those who wanted to avoid addressing those ideologies by name.”

Ascol — whose brother, Bill, was the chief advocate for adoption of a resolution calling for an absolute end to abortion in America without exception — often represents the most far-right ideology within the convention. That is evidenced by the fact that he labels many of the SBC’s current leaders, who are by any other standards extremely conservative, as “elites” who are out of touch with grassroots Southern Baptist thought.

Rooting out anything related to Critical Race Theory has been a key objective of both Founders Ministries and the Conservative Baptist Network. And to hear some of these Baptist pastors tell it — or tweet it — the SBC faces an imminent threat from the teaching and accommodation of Critical Race Theory.

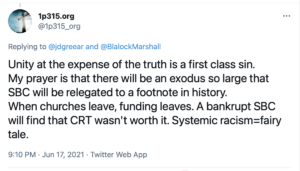

One critic of the SBC leadership tweeted June 17: “Unity at the expense of the truth is a first class sin. My prayer is that there will be an exodus so large that SBC will be relegated to a footnote in history. When churches leave, funding leaves. A bankrupt SBC will find that CRT wasn’t worth it. Systemic racism = fairy tale.”

One critic of the SBC leadership tweeted June 17: “Unity at the expense of the truth is a first class sin. My prayer is that there will be an exodus so large that SBC will be relegated to a footnote in history. When churches leave, funding leaves. A bankrupt SBC will find that CRT wasn’t worth it. Systemic racism = fairy tale.”

Many similar posts insisting that the SBC has fallen into bed with Critical Race Theory and other forms of liberalism populated Twitter and Facebook during and after the annual meeting.

Seminary presidents take the lead

Of late, the six SBC seminary presidents have taken the lead in addressing such accusations, issuing a joint declaration last Nov. 30 that Critical Race Theory is not and will not be taught in their schools. That denunciation stirred ire among Black SBC pastors who heard in it a denial of systemic racism. And it stirred doubt among some other SBC pastors and lay leaders who still believe — with no evidence or documentation — that the seminaries are secretly teaching this academic construct.

Thus, it was not surprising to anyone when during the joint report of the six seminary presidents to the SBC annual meeting questions were asked about Critical Race Theory.

Adam Greenway (Baptist Press)

Adam Greenway, president of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, gave an extended answer to one messenger’s question. That messenger, a young pastor, asked if the seminaries together might produce some kind of resource to explain Critical Race Theory in layman’s terms and to outline where it is in conflict with the Baptist Faith and Message, the SBC’s primary doctrinal statement.

Greenway took the occasion — as Southern Baptist Theological Seminary President Al Mohler had done a few moments before in response to another messenger question — to reaffirm the unanimous resolve of the six seminary presidents against Critical Race Theory. What was said in the presidents’ Nov. 30 statement was the minimum that must be said about the issue, and there is much more that could be said, both Greenway and Mohler noted.

In fact, he said, if he went out on the floor of the convention and asked 20 people what they believe Critical Race Theory means, he was certain he would get 20 different answers.

However, it was Greenway who dug in on the issue, beginning with his belief that few people who are concerned about Critical Race Theory would agree on a definition. In fact, he said, if he went out on the floor of the convention and asked 20 people what they believe it means, he was certain he would get 20 different answers.

It is the original, academic construct known as Critical Race Theory that is antithetical to the gospel and to the Baptist Faith and Message, he said emphatically.

However, when the seminary presidents denounced that construct, what many non-Anglo pastors in the SBC heard them say was that they don’t believe systematic or structural racism is real, Greenway added. And that is not what the seminary presidents meant, he said, going so far as to offer a personal, blanket apology to any who have taken offense at his own words on the matter.

Even these emphatic comments by Greenway and Mohler didn’t satisfy some critics, who took them to task on Twitter and Facebook for allegedly covering up a Critical Race Theory agenda at the seminaries.

Effort to repeal Resolution 9

Part of what animated the discussion at this year’s annual meeting was a desire by the rightward flank of the denomination to repeal a resolution passed at the 2019 SBC meeting. That statement, known as Resolution 9, largely warned against Critical Race Theory but did allow that as an analytical tool that might “aid in evaluating a variety of human experiences” but only if employed “as analytical tools subordinate to Scripture — not as transcendent ideological frameworks.”

Despite multiple paragraphs in the 2019 resolution warning about the misuse of Critical Race Theory, the two paragraphs not denouncing it as pure evil are what drew the ire of the most conservative branch of the denomination. Almost from the moment the 2019 resolution was passed, a campaign began to repeal it.

Resolutions adopted by prior conventions cannot be amended or rescinded.

The problem is that — in parliamentary terms — resolutions adopted by prior conventions cannot be amended or rescinded. That is because in the SBC’s bylaws, resolutions are non-binding and merely express the sentiment of the messengers assembled that year. They are not like motions that set in motion specific actions or set policies.

Nevertheless, some messengers came to this year’s Nashville meeting determined to rescind Resolution 9. On the second day of the meeting, convention President J.D. Greear acknowledged from the platform the frustration some were feeling because they could not accomplish what they wanted.

Greear called on one of the convention’s attorneys, James Jordan, to explain the situation. Jordan noted that one year’s convention “cannot nullify the fact that a previous convention expressed an opinion. … You can disagree with a previous group of messengers but you cannot nullify that they expressed that opinion.”

The workaround

So the workaround was to bring forth a new resolution that both corrected the perceived errors of the 2019 resolution while setting a new standard. That option was not good enough for some, however, who were determined to expunge the record of the 2019 resolution as though it never existed.

Prior to the convention, several iterations of new draft resolutions denouncing Critical Race Theory were circulated. At least one was copied and sent over and over again to the Committee on Resolutions by a reported 1,300 people from a handful of churches.

Prior to the convention, several iterations of new draft resolutions denouncing Critical Race Theory were circulated.

That proposed resolution for the 2021 meeting, supported by SBC presidential candidate Mike Stone of Georgia, would have taken on Critical Race Theory by name, calling it and the related academic notion of intersectionality “ideologies rooted in Neo-Marxist and postmodern worldviews, by which our civilization is being deconstructed around our families, communities and nations.”

The Committee on Resolutions, which was chaired by former SBC president and longtime Georgia pastor James Merritt, didn’t take the bait, however. All proposed resolutions must go through the Resolutions Committee, where they often are combined or rewritten — if put forward at all.

On the first day of the convention, the Resolutions Committee brought forth its own resolution “On the Sufficiency of Scripture for Race and Racial Reconciliation.” That resolution did not cite Critical Race Theory by name but said the SBC rejects “any theory or worldview that finds the ultimate identity of human beings in ethnicity or in any other group dynamic” or that “sees the primary problem of humanity as anything other than sin against God and the ultimate solution as anything other than redemption found only in Christ.”

The committee’s intent was to denounce Critical Race Theory without giving further offense to Black pastors and churches that had left or were threatening to leave the denomination over the seminary presidents’ previous statement.

Although challenged from the floor and debated, the committee’s resolution ultimately was adopted by the convention. And efforts to rescind Resolution 9 from 2019 were ruled out of order.

Responses

Dwight McKissic

Texas pastor Dwight McKissic, who is Black, has been a vocal inside critic of the SBC and its failures to address both its historic roots in racism and its modern-day denial of the reality of racism. The actions of this year’s convention on race and Critical Race Theory earned his praise.

“The SBC resolutions committee has responded correctly twice to CRT resolutions,” he tweeted. “The convention voted correctly twice. The council of seminary presidents are still way off base, with their CRT position & response. I’m grateful that the SBC position trumps the CSP position on CRT.”

Ascol, in his convention summary blog posting, issued another call to battle for the far-right faithful: “It is time for Southern Baptist churches, led by God-fearing pastors, to show up, stand up, and speak up, and remind the elites and our erstwhile leaders that the seminaries, institutions, and agencies of the SBC belong to the churches.”

Related articles:

Why Critical Race Theory could be good news for ‘nice white people’ | Opinion by Craig Nash

It’s not just the SBC banning Critical Race Theory; now state legislatures are joining the fight

Could you win a quiz show by defining ‘Critical Race Theory’? | Analysis by Mark Wingfield