I was in the room when the respected and enduring leader of the Southern Baptist Convention Executive Committee, Porter W. Routh (1951-79), spoke to journalists in Houston after the election of Adrian Rogers to the convention presidency in 1979.

Rogers was the “breakthrough” candidate representing a faction of ultraconservatives initiating a process of turning the convention toward a new direction. These “inerrantists” intended to use the appointive powers of the president to pick trustees of the SBC boards, agencies and institutions favorable to their cause.

“There’s just no way that presidents of the SBC could reach a goal of replacing enough trustees of the various organizations to alter the convention’s direction.”

The crowd in the press room that day consisted of several hundred religious and secular reporters. We listened intently as Routh responded to the action of the convention messengers. He expressed something like this: “There’s just no way that presidents of the SBC could reach a goal of replacing enough trustees of the various organizations to alter the convention’s direction. It would literally take years to achieve, and nobody is going to give it that much effort.”

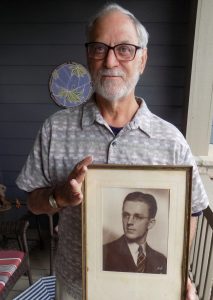

Porter Routh (seated) as secretary of the SBC in 1951.

I’ve reflected on his words many times since, wondering what Routh thought in the eight years he lived into retirement after those remarks. By then, the makeover he summarily dismissed was well on its way to fruition.

While the convention’s literal transition was begun in 1979, some three decades earlier the congregation in which I grew up was starting to emerge as the antithesis of fundamentalist postures. At the time, we didn’t know that, in due course, we were going to be out of the mainstream of Southern Baptist thought, at least that of newly formed Officialdom.

Living the dream earlier

As I think back on it now, I realize that St. John’s Baptist Church in Charlotte, N.C., was living the dream that eventually would signify us as denominational mavericks — SBC liberals, more often dubbed “moderates” — that we were. As our church evolved, some practices we engaged in were in direct contradiction to views favored by the SBC. But most of us clearly didn’t realize it at the time.

What we did know was that we were a harmonious fellowship of baptized believers practicing corporate worship with extra pursuits that embraced good times. We unpretentiously enjoyed the company of one another and sought countless occasions to experience it. It hadn’t dawned on most of us that there were Baptists who could take a dim view of some of our activities.

By the time a spacious Fellowship Hall was opened in a new educational wing in 1952, we were intermittently holding square dances there on Friday and Saturday nights. The instructor tutoring us in those steps was our own experienced square dance caller, Pastor Claude U. Broach. When church families traveled to a mountain retreat for a week at Little Switzerland, N.C., in the 1950s over six consecutive summers, parson Broach called the nightly square dances.

St. John’s Baptist Church early photo

The minister did the same at some legendary country hoedowns at the church’s camping complex in forested acreage northeast of Charlotte at Crab Orchard Township. St. John’s Camp, a 13-acre tract with several structures erected by volunteer labor, was donated to the congregation in 1946 by a generous member. That may have led to our downfall, when we first began to skirt some of the traditional practices commonly held by our denomination. That same individual had given the congregation an earlier campsite in today’s nearby Paw Creek Township plus a lot at Ridgecrest (N.C.) Baptist Assembly for church use.

I recall some excursions a handful of church families made to the coast on Labor Day weekends in the 1950s. While the offspring got in loads of beach time, the adults were engaged in marathon Canasta tournaments. At least one of those events and maybe more transpired at a seaside state Baptist assembly. The Broaches were along for some of those ventures. The card-playing would have been blasphemy to many Baptists of that era (as well as now). Yet if it bothered us, I don’t remember hearing it expressed.

Race relations and ecumenism

Broach served the St. John’s congregation three decades (1944-1974). He fostered positions that would have been scorned by many of the brothers and sisters of our faith. He devoted significant emphasis to race relations and ecumenism in a period in which neither would have been widely accepted. In 1954, he was one of the earliest white ministers to unconditionally welcome the Supreme Court’s ruling stripping away constitutional sanctions of ethnic segregation. Much of his energy beyond that time was devoted to supporting lobbies favoring equality among the races.

“He devoted significant emphasis to race relations and ecumenism in a period in which neither would have been widely accepted.”

The St. John’s pastor of the mid-20th century led myriad alliances advocating better understanding and acceptance of religious sects including Protestants, Catholics and Jews. Much of Broach’s later life, including retirement, was devoted to that cause. While this might have been anathema to many Southern Baptists, it received repetitive exposure at St. John’s.

Separation of church and state

The historic Baptist tenet of separation of church and state that was practiced by nearly every Southern Baptist church at the time was fervently advocated by Broach. Not once in my memory did I ever hear him favor a political party or hint for whom we should vote in elections. Today thousands of ultraconservatives in autocratically dominated SBC congregations never hear of the principle of separation of church and state. St. John’s has faithfully upheld that cherished Baptist canon across the ages.

Claude Broach Jr. holds a framed photo of his father, Pastor Claude U. Broach..

Believing everyone is created with equal access to the Holy Spirit regardless of a person’s background, culture, status, gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation, St. John’s adopted an unpopular stance early. It was among the vanguard of SBC congregations taking the unusual (for that time) step of ordaining female deacons. It subsequently certified women ministers.

In contemporary times the body has patently extended church membership to mixed couples, LGBTQ, transgender — literally “all persons” — no matter what their alleged baggage. These actions are disturbing to many in some SBC churches. Many have cast aspersions on St. John’s for going against ingrained insular interpretations of the gospel.

An early warning

After attending the 1963 meeting of the SBC in Kansas City, St. John’s associate pastor, Roberts C. Lasater, is quoted in the church’s half-century history (Fifty Favored Years). Lasater observed that he witnessed “pressure groups of ultraconservative people who are seeking to dominate the convention. They are not our kind of Baptist, and they are trying to make our denomination something it has never been. If they succeed, the convention will be split asunder.”

“If they succeed, the convention will be split asunder.”

This was 16 years prior to the “breakthrough” the fundamentalists achieved — and multiple years would pass after that until their goal of running the convention their way was realized. Nevertheless, their tenacity would not be thwarted. The foundations of the SBC must have begun to quiver by 1963 for sure.

Yet a normal SBC church too

Despite its uniqueness in creating some different features and taking a few actions that raised eyebrows among some Southern Baptists, St. John’s observed most practices their fellow churchgoers did for decades. From its earliest days, the congregation implemented a customary Nashville-inspired format on Sunday mornings, Sunday nights and Wednesday nights.

The midweek prayer meeting after a fellowship supper was among the weekly highlights with missions and music activities for younger ages. St. John’s cultivated a fully graded choir program, WMU circles and Brotherhood endeavors. January Bible Study was on the docket in winter. Vacation Bible School was a prominent part of June’s agenda. Anything endorsed by the SBC usually was on St. John’s recurring itinerary. In this way the church demonstrated its cooperative spirit as a team player.

From the 1940s, the church maintained a professional staff comprised of a pastor, associate pastor (added later), and ministers of music, education, youth and children’s work. That team increased as specific needs arose in contemporary times. The sanctuary and initial education facility remained on the residential corner originally occupied in the 1920s. Yet as membership grew the congregation expanded into lots more space, eventually purchasing most of the block surrounding it.

“Throughout its life, St. John’s has manifested a strong heartbeat for missions.”

Throughout its life, St. John’s has manifested a strong heartbeat for missions. Between the 1940s and 1960s, it fostered three new Southern Baptist congregations in its city. In 1949, it began to sponsor and integrate into membership many Latvian immigrants fleeing their homeland. St. John’s directly supported separate institutions of its state Baptist body while giving up to $50,000 in some years to the North Carolina organization. The church aided Mecklenburg Baptist Association in many ways as it was asked. St. John’s paid its pledge to that body in full each year and sent an unspent budget overage to the association at least once.

No good deed goes unpunished

Do you recall the maxim, “No good deed goes unpunished”? Despite its noble intents, some of St. John’s brothers and sisters took a dim view of the church’s progressively liberal leanings and murmured among themselves. Increasingly their concerns turned into discussion topics in private and in public. As that crescendo grew louder, St. John’s had become an irritant a certain segment no longer could tolerate.

Trouble in the amen corner came initially in Mecklenburg Baptist Association. In March 1967, St. John’s altered its baptismal policy to accept people of other faiths without immersion when they experienced “an act of obedience following conversion.” If not that, immersion ensued. This prompted a rupture in the association. At its annual meeting in October 1967, the local pact voted 214-130 to amend its bylaws. Candidates for membership in affiliated churches must be immersed in water from then on, whatever their previous circumstances. There was no lenience for deviation.

St. John’s messengers — and some others — interpreted the action by Mecklenburg Association as “creedal authority” and zealously opposed it. Richard Young’s history alleges: “It became obvious that the association was intent on excluding St. John’s and other churches.” In October 1968, at the group’s next annual session, a statement from St. John’s deplored the “creedal or doctrinal test” as a condition of membership. “We are well aware of its real intent,” the statement conjectured. With that the church withdrew its membership in the association.

As the division within the SBC widened, St. John’s continued to move outside its affiliations with the larger Baptist bodies that existed during those days. During a pastoral transition in 1987, St. John’s called Tom Graves as senior minister. He had been a professor at Southeastern Seminary, which now was under control of the fundamentalists. He departed St. John’s in 1991 to become the founding president of Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond. It was the first seminary begun by progressive Baptists outside the SBC.

Excluded for being too inclusive

Four decades after the baptismal schism, St. John’s was in hot water again, this time for accepting gays as members. It was something the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina simply could not abide. St. John’s was one of nearly a score of congregations on the hook with the state body for this infraction. In November 2006 at Greensboro in annual session, these Tar Heel Baptists voted to “investigate and expel” affiliated churches that accepted members in violation of its policies. Three months hence, in February 2007, St. John’s withdrew from the state alliance.

“Why wait for someone to tattle on you?”

Richard Kremer, then St. John’s pastor, expressed his reaction to a reporter: “They probably would have expelled the church. … Why wait for someone to tattle on you? … We prefer … a different direction.”

Richard Kremer

Kremer noted the church and convention had been “at odds” for a while. The state body, he said, considered St. John’s “a pariah” and “blackballed” members seeking state Baptist leadership posts. St. John’s summarized the split by stating the North Carolina convention narrowed membership to exclude churches not following its “exclusive discriminatory view of who is welcome.”

A decade earlier, St. John’s members voted overwhelmingly to pull out of the Southern Baptist Convention as well. Realizing the convention was greatly troubled by the then-completed takeover by the fundamentalists — knowing that St. John’s had long been widely identified as a moderate church — the congregation believed after 75 years of cooperation that separation was best for its future.

While St. John’s was no longer actively participating under the SBC umbrella, officials at convention headquarters didn’t quite see it that way. St. John’s obviously was running counter to the direction of the national convention, yet repeatedly its declaration of independence appeared to fall on deaf ears.

Most moderate Baptist congregations are included in the SBC tally of “who’s in” long after they stop participating in the SBC, according to a 2004 news story. There is a better chance of “stopping the sun rising in the east than getting off the list,” said pastor Richard Kremer. “It’s not for lack of trying. We’ve called everyone we know to call” and sent back mail marked “return to sender.” He acknowledged that “it’s pretty much impossible.”

“Because we are a church that welcomes anyone, we realize we cannot be a church for everyone.”

That was then. Today it’s a broadly established fact that St. John’s operates outside SBC boundaries. Now it’s affiliated with 10 more entities: Alliance of Baptists, Association of Welcoming and Affirming Baptists, Baptist Peace Fellowship of North America, Baptist Women in Ministry, Baptist World Alliance, Cooperative Baptist Fellowship (national and state), Elizabeth Communities of Faith, Mecklenburg Metro Interfaith Network, and North Carolina Council of Churches. In addition, the church supports Baptist Retirement Homes of North Carolina plus Mars Hill, Wake Forest and Wingate universities.

Dennis Foust

Given an opportunity to respond to this story, today’s St. John’s senior minister, Dennis Foust, who has been there since August 2011, offered his reflections on St. John’s enduring impact: “This is our centennial year. From our first days until now, we have embraced the freedom and responsibility of our autonomy. We choose to be a local Baptist church expressing God’s good news through a theologically progressive witness focused upon Jesus’ example of servant faith. We have a clear identity and message and refuse to waffle. We partner with groups that collaborate and refuse to partner with any group seeking to control us. Because we are a church that welcomes anyone, we realize we cannot be a church for everyone.”

For several decades of the 20th century, the church’s motto appeared at the top of a weekly newsletter: For the glory of God, a greater St. John’s! The glory may have differentiated from the practices of many congregations applying Baptist nomenclature. Nevertheless, I’m of the opinion that God is honored by the fellowship St. John’s has perpetually espoused. Its interpretation of the Scriptures goes well beyond the straight and narrow as it perceives Christ’s bidding to the strangers at its gates in an incredibly distinctive and joyous expression of “y’all come.”

Jim Cox

Jim Cox has been a journalist for a Southern Baptist board, agency and institution. A graduate of Vanderbilt and Webster universities, he holds dual master’s degrees. For many years he prepared Sunday school and vacation Bible school curriculum for Southern Baptists while penning devotionals and articles on a profusion of topics for magazines, newspapers and newsletters of multiple denominations. He was press representative at Ridgecrest Baptist Assembly several summers and is the author of 23 books.

Related articles:

Lost Boys of Sudan: St. John’s Baptist Charlotte

Two more churches leave NC convention over gay policy

Pastor blasts biblical inerrancy

Second Easter during pandemic brings greater sense of hope nationwide