After Congressional votes to override former President Donald Trump’s veto of the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, the stage is set for renaming up to 10 military bases and a variety of military assets named after Confederate war heroes.

Among funding an array of military programs and services, the 2021 NDAA includes a provision for naming a commission to review and remove all commemorations of Confederate war heroes from all assets owned by the Department of Defense.

Trump repeatedly cited his objection to renaming bases as a primary rationale for his veto of the annual appropriations bill. In contrast, both houses of Congress broadly agreed that the 60-year tradition of passing the annual funding bill must continue to ensure unbroken funding of vital U.S. military personnel and security interests.

Why are bases, ships and streets named after Confederate war heroes?

The now infamous 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., spurred many municipalities and institutions to re-examine Confederate symbols as a response to public outcries. A subsequent 2017 study by the Army Center for Military History traced the origins of bases “named for individuals who had fought against the United States and the U.S. Army during the American Civil War.”

That study found that prior to 1878, a historically informal process enabled local commanders to select and name military posts for heroic individuals such as George Washington and James B. McPherson. General Order Number 79 published by the War Department in 1878 sought to secure uniformity in the naming process by reserving naming rights for regional commanders.

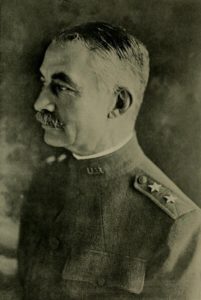

Joseph Kuhn

In 1917, Gen. Joseph E. Kuhn of The General Staff’s War College Division sought to clarify three key criteria for naming posts: (1) the name should represent a person from the locale of the troops stationed there; (2) that the name be “not unpopular in the vicinity of the camp,” and; (3) the name should focus on “federal commanders for camps of the divisions from Northern States and of Confederate camps of divisions from Southern states.“

The 2017 study found, however, that in practice, criteria evolved over time and were sometimes ignored, often in order to bow to regional political pressure.

The motive for sanctioning and even encouraging Confederate names for posts was that it was done as an act of reconciliation, a post-Civil War accommodation for Southern states, local communities and soldiers who might be offended by names of Union heroes attached to bases in their area.

As the buildup of bases occurred largely between World War I and World War II, when the South was fiercely segregated during the Jim Crow era, accommodation was focused squarely on white politicians, white citizens in local communities and the sensitivities of white soldiers. More practically, the U.S. War Department needed to purchase vast tracts of land in the early 20th century to expand its military training capacities.

Naming of bases is a time-tested means of endearing a project to local communities. Continuing this rationale as recently as 2015, Pentagon representatives such as Brig. Gen. Malcolm B. Frost have resisted renaming military posts named after Confederate generals contending that “the naming occurred in the spirit of reconciliation, not division.”

Why rename these posts?

Proponents of renaming posts typically cite one or more of the following rationales:

First, military bases are supposed to be named for exemplary heroes who faithfully served their country, yet Confederate namesakes were traitors to their country.

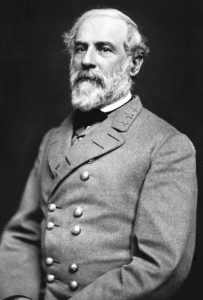

Robert E. Lee

Second, aside from Gen. Robert E. Lee, the majority of Confederate namesakes were not exemplary leaders, but often persons of nominal capabilities and limited success in battle. Former Army General and CIA Director David Petraeus wrote last year in the Atlantic that most namesakes “were undistinguished, if not incompetent, battlefield commanders.”

Third, it is morally offensive to today’s soldiers of color to have them serve on a base named after an enemy of the United States who oppressed their race. Furthermore, people of color make up a disproportionate share of the present-day military; serving on bases named after defenders of slavery is particularly insulting to people in uniform on a daily basis.

The 2017 report spurred little action, however, other than the renaming of Lee Barracks at the U.S. Military Academy, named after Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Since then, national protests over police violence against persons of color, embodied in the Black Lives Matter movement, have shone a spotlight on the legacy of systemic racism perpetuated by a range of American institutions. As Confederate monuments and flags recently were taken down across the country, senior Department of Defense officials, including Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and Secretary of the Army Ryan McCarthy, publicly signaled openness to reconsider renaming military assets.

For many, yesterday’s act of reconciliation, no matter how well intended, has become a perpetual tribute to insurrection and a vanquished vision of racism that disrespects people of color past and present.

Priority posts and assets for renaming

As the oldest branch of the U.S. military, the Army will face the lion’s share of renaming assets. Ten active posts are named for Confederate war heroes, including the three largest bases in the country. See the attached chart for details.

In addition to Army posts, the U.S. Navy has identified four ships with problematic names associated with the Confederacy or racial segregation. The guided-missile cruiser Chancellorsville was named after a critical battle won by the South, and the survey ship Maury was named after an innovative oceanographer who resigned a U.S. Navy commission to join the Confederate Navy. Additionally, the carrier Carl Vinson and the carrier John Stennis are named after Southern politicians who publicly backed racial segregation while also being steadfast supporters of the Navy.

In addition to Army posts, the U.S. Navy has identified four ships with problematic names associated with the Confederacy or racial segregation. The guided-missile cruiser Chancellorsville was named after a critical battle won by the South, and the survey ship Maury was named after an innovative oceanographer who resigned a U.S. Navy commission to join the Confederate Navy. Additionally, the carrier Carl Vinson and the carrier John Stennis are named after Southern politicians who publicly backed racial segregation while also being steadfast supporters of the Navy.

The commission also is charged with planning how to remove other displays, monuments and public objects that honor the Confederacy, although grave markers are exempt. The language used to define the term “assets” in the 2021 NDAA includes “any base, installation, street, building, facility, aircraft, ship, plane, weapon, equipment, or any other property owned or controlled by the Department of Defense.”

Process and timeline for renaming military posts

The 2021 NDAA calls for the process of naming the commission and implementing the name review plan to be overseen by the Secretary of Defense. Four-star Army Gen. Lloyd Austin recently was confirmed by the Senate as the first Black defense secretary in the nation’s history.

Austin is on record for making the eradication of systemic racism in the military a major priority. Facing confirmation hearings just weeks after the deadly insurrection at the U.S. Capitol led by a large number of current and retired military veterans, Austin told senators that the Pentagon’s job is to “keep America safe from our enemies. But we can’t do that if some of those enemies lie within our own ranks.”

The commission is to consist of eight members, with four appointed by the Secretary of Defense, one each by the Chairman of the Armed Services Committees in the Senate and House, and one each by the ranking member of the Armed Services Committees of the Senate and the House. Prior to Austin’s appointment and approval, Acting Secretary of Defense Chris Miller appointed to the commission Sean McLean of California, Joshua Whitehouse of New Hampshire, Anne G. Johnston of North Carolina and Earl Matthews of Pennsylvania. To date, it is unclear whether these appointments will stand or be subject to further review.

The timeline for the work of the commission and implementation of its recommendations calls for all work to be completed within three years of approval of the 2021 NDAA. The 2021 NDAA was enacted on Jan. 1, 2021.

Major benchmarks include:

- Commission appointed within 45 days (Deadline: Feb. 15, 2021)

- Initial meeting within 60 days of enactment (Deadline: March 1, 2021). The commission will be tasked with developing lists of assets, costs associated with removal or renaming assets, criteria used to rename assets, methods for collecting and considering local sensitivities toward removal or renaming assets.

- Five months to conduct review and make recommendations (Deadline: Oct. 1, 2021) when the committee will brief the Armed Services Committees and the Senate and House. This briefing also must occur at least 90 days before any implantation action is taken.

- The timeline presumably leaves the subsequent two years for implementation beginning in 2022.

With the stage set, the commission faces a monumental task that will certainly encounter the perennial tension between national interests and local sensitivities. But with the shifting culture, many will be watching to see if considering local sensitivities this time around means just white citizens, or every citizen.

Brad Russell serves as vice president of a marketing research firm focused on smart technologies. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Texas at Austin, a master of divinity degree from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, and a doctor of ministry degree from Austin Presbyterian Seminary. Previously he served a variety of Baptist churches and institutions in Texas.

Sources for additional reading:

- https://federalnewsnetwork.com/defense-main/2021/01/in-a-first-congress-overrides-trump-veto-of-ndaa/

- https://federalnewsnetwork.com/defense-main/2020/12/house-set-for-override-vote-on-trumps-defense-bill-veto/

- https://fcw.com/articles/2021/01/01/ndaa-veto-overturned-senate.aspx

- https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2020/10/14/a-2017-army-study-examined-naming-of-posts-for-confederates-but-nothing-came-of-it/

- https://history.army.mil/faq/naming-of-us-army-posts.htm

- https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/s4049/text

- https://apnews.com/article/race-and-ethnicity-biden-cabinet-lloyd-austin-army-4b92df07f4c319deeb7d6a94ae9af60a

- https://yellowhammernews.com/pentagon-wont-rename-alabamas-ft-rucker-named-after-confederate-officer/

- https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/military/story/2020-07-26/navy-ship-naming-controversy#:~:text=Two%20of%20them%20have%20ties,U.S.%20Navy%20to%20join%20the

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2020/06/10/trump-confederate-bases/

- https://www.stripes.com/news/us/defense-secretary-appoints-four-to-commission-on-renaming-military-bases-that-honor-confederates-1.657911

- https://www.politifact.com/article/2020/jun/16/military-bases-named-confederates-renaming-suggest/

- https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/take-confederate-names-off-our-army-bases/612832/

- Various Wikipedia pages for posts and namesakes