In 1993, AT&T launched an ad campaign now famous for its accuracy about future technologies. The ad showcased video calls, tablet computers, eBooks, personal GPS navigation and the digital classroom. The central theme was the erasure of space. When checking out a library book, attending school or running a business meeting, space was no longer an issue. The moment intended to tug your heartstrings was a mother wishing her child goodnight from a phone booth video call (it didn’t get everything right). The message was simple: digital connection will erase the limitations of space. Physical space was an obstacle to overcome, a difficulty in need of elimination, or a problem in need of solving.

In 1993, AT&T launched an ad campaign now famous for its accuracy about future technologies. The ad showcased video calls, tablet computers, eBooks, personal GPS navigation and the digital classroom. The central theme was the erasure of space. When checking out a library book, attending school or running a business meeting, space was no longer an issue. The moment intended to tug your heartstrings was a mother wishing her child goodnight from a phone booth video call (it didn’t get everything right). The message was simple: digital connection will erase the limitations of space. Physical space was an obstacle to overcome, a difficulty in need of elimination, or a problem in need of solving.

Recently, we have seen a perplexing resurgence in interest in physical space, particularly within the most tech-savvy generations. One of the weirdest fads in recent memory is an “augmented reality” game. Pokémon Go sends players walking around their neighborhoods to find digital monsters in the real world. There are countless tales of erstwhile millennial hermits discovering new worlds outside. Parks, churches, museums and monuments have encountered numerous new visitors seeking their pocket monsters. Pokémon Go and “augmented reality” is interesting because it bucks the trend AT&T capitalized on in its campaign. Physical space was important again.

Augmented reality is different from virtual reality because it prizes physical space. Despite the despondent account of duplicitous virtual reality in 1999’s The Matrix, technology has skewed in the virtual reality direction. Video games have become more realistic in their appearance. Movies have attempted to become more immersive. Large theaters now have auditoriums with three-dimensional imagery, sound systems that shake your seat, and screens that fill your field of vision. The goal is to replace the reality we experience with another one. Augmented reality, on the other hand, prizes reality to an extent. It requires you to be present and engaged in the world outside your door. Augmented reality requires you to walk, explore and encounter the world around you.

Augmented reality is different from virtual reality because it prizes physical space. Despite the despondent account of duplicitous virtual reality in 1999’s The Matrix, technology has skewed in the virtual reality direction. Video games have become more realistic in their appearance. Movies have attempted to become more immersive. Large theaters now have auditoriums with three-dimensional imagery, sound systems that shake your seat, and screens that fill your field of vision. The goal is to replace the reality we experience with another one. Augmented reality, on the other hand, prizes reality to an extent. It requires you to be present and engaged in the world outside your door. Augmented reality requires you to walk, explore and encounter the world around you.

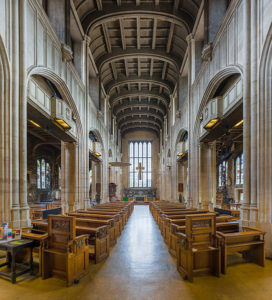

This emerging technology reminds us that place matters. For churches, and the spiritual among us, it presents an opportunity to renew our appreciation of place. A personal example might help. During college, I spent a semester studying in London. While I was there, I began to take part in the Wednesday night worship at All Hallows by the Tower, a Church of England congregation near the Tower of London. They hosted a Taizé worship service unlike most worship gatherings I have experienced elsewhere. We gathered in the sanctuary’s sometimes-rickety pews underneath its thrice-restored ceiling. Clouds of incense wafted past us from the burning bowl in front of the altar. Tiny candles were strewn across the floor, our only light apart from the setting sun. As we sang chants in multiple languages and heard readings from Scripture, one of the busiest cities in the world outside the sanctuary faded away. The place in front of us became our only reality, an intense moment of presence in space.

This emerging technology reminds us that place matters. For churches, and the spiritual among us, it presents an opportunity to renew our appreciation of place. A personal example might help. During college, I spent a semester studying in London. While I was there, I began to take part in the Wednesday night worship at All Hallows by the Tower, a Church of England congregation near the Tower of London. They hosted a Taizé worship service unlike most worship gatherings I have experienced elsewhere. We gathered in the sanctuary’s sometimes-rickety pews underneath its thrice-restored ceiling. Clouds of incense wafted past us from the burning bowl in front of the altar. Tiny candles were strewn across the floor, our only light apart from the setting sun. As we sang chants in multiple languages and heard readings from Scripture, one of the busiest cities in the world outside the sanctuary faded away. The place in front of us became our only reality, an intense moment of presence in space.

This is what the ancient Celts, indigenously religious and Christian, called “thin places.” I have heard about thin places so many times, it borders on pastoral cliché. Nevertheless, I believe it has currency right now — it helps us understand place and what role spaces can play in our lives. Another example of a thin place is an island off the coast of Ireland called Skellig Michael. Recently made famous as the setting for the end of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Skellig Michael rises out of the sea like a defiant objection to the tumultuous sea around it. An early Christian monastery sits on the island northeast of what the monks called “Christ’s Saddle.” The title speaks to the closeness of God to this place. It is where Christ sits and this island is the place from which he embarks to see the world. It is worth noting that the thin place at Skellig Michael is as treacherous to get to as it is marvelous to behold, which is true of many places that truly achieve the title sacred.

This is what the ancient Celts, indigenously religious and Christian, called “thin places.” I have heard about thin places so many times, it borders on pastoral cliché. Nevertheless, I believe it has currency right now — it helps us understand place and what role spaces can play in our lives. Another example of a thin place is an island off the coast of Ireland called Skellig Michael. Recently made famous as the setting for the end of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Skellig Michael rises out of the sea like a defiant objection to the tumultuous sea around it. An early Christian monastery sits on the island northeast of what the monks called “Christ’s Saddle.” The title speaks to the closeness of God to this place. It is where Christ sits and this island is the place from which he embarks to see the world. It is worth noting that the thin place at Skellig Michael is as treacherous to get to as it is marvelous to behold, which is true of many places that truly achieve the title sacred.

What can Christian communities learn from this emerging insistence on space and the ancient concept of sacred place? It is a valid question, perhaps asked incredulously. Churches, like many other brick-and-mortar institutions in our country, are apparently on the decline space-wise. Ministers and laity alike are pitched ideas for digital cathedrals and virtual abbeys, spiritual gatherings unmoored from the constraints of physical space. A cursory overview of church websites makes it readily apparent that most Christian communities have roundly rejected this advice. While that response may have been rooted in some unsavory motivations (e.g., unwillingness to change and adapt), there is something to be said for the brick-and-mortar that still comprise a crucial part of congregational life. There are some experiences that are increasingly rare outside of churches, like intergenerational mingling, corporate singing and public proclamation. One of those unique experiences our churches may soon be able to offer is the brick-and-mortar thin place of physical space. After all, most churches are stops or gyms in Pokémon Go. But more seriously, churches possess a unique offering in their grounded, physical location that should not be overlooked.

Churches should honor their sanctuaries as potential thin places. As travel writer Eric Weiner put it, “Not all sacred places, though, are thin.” Many churches can find their sanctuaries’ air stale with the scent of conflicts long gone, animosities seeping up from beneath the surface, or even the invasive odious odor of busyness from outside its walls. The historical matters that thicken the places of our sanctuaries must be dealt with contextually, but the infiltration of the harried pace of the outside can be countered. When I talk about worship planning with congregations I serve, I talk about it as an architectural project. It is different than the planning that goes into a press conference or a convention. The architectural vision that gives us concert halls, stadiums, and monuments attempts to create space for an experience. Our worship should create a space for the participants to encounter God. We do convey a certain amount of information in our services, yes, but when we plan, we should build a sacred environment in which our people can meet the God we are talking about. In doing so, we lose our control over the place, surrendering it to the sacred encounter, to the Spirit. But in our loss of control, we may just thin the place enough for heaven to break in.

Churches should also make their sanctuaries worthy of the name, safe places with communal support and inclusion. The augmented reality of Pokémon Go, the strange sanctuary of All Hallows, and the isolated monastery of Skellig Michael all created places for people to gather and safely enjoy each other over a common passion. That’s why it’s so painful when these safe places are violated. There was controversy when Star Wars filmed at a place like Skellig Michael. When some used Pokémon Go to rob players, it was a violation of a safe place. Most severely, when a white supremacist murdered black churchgoers at Mother Emanuel, it shook the nation. Our churches should be safe spaces, sanctuaries for all people in a world that seems to regard no space as sacred. A physical space where one doesn’t have to worry about harassment, assault, and all other sorts of vitriol is rare — and it’s something our churches could strive to offer. That’s no small commitment to make because it would require our churches to engage uncomfortable issues of race, gender, class and sexuality. Nevertheless, it is a task that is increasingly necessary in our world.

Churches should share their places, because space is not just about experience but power. As we recognize the importance of physical space, our churches must recognize the power of place that they hold. Power, in the United States especially, has always been tied to space. You used to need to own land to vote, segregation enforced racialized power, and gentrification and urban development in our cities is consolidating power in the hands of the few. Churches can seek to rebuff these trends by sharing their places and spaces with those who don’t have them. Churches should volunteer their spaces for community meetings and activities as well as using these spaces to care for those who have no safe space. That means everything from taking advantage of your church’s Pokémon gym to providing a warm place to sleep for the homeless to serving as a gathering place for community activism. Recognize the asset and power that your church has in its land and brick-and-mortar, and share that power with your community.

Serving as a steady space in an unsteady world is one of the roles our churches can serve in a sometimes scary and disconcerting future. Church will look dramatically different in the decades to come. However, humanity will not stop having sacred experiences, needing safe spaces, and requiring the power to gather. If our churches invest our energies and resources into using our places and spaces in some of these ways, we might find something of a future worth having.