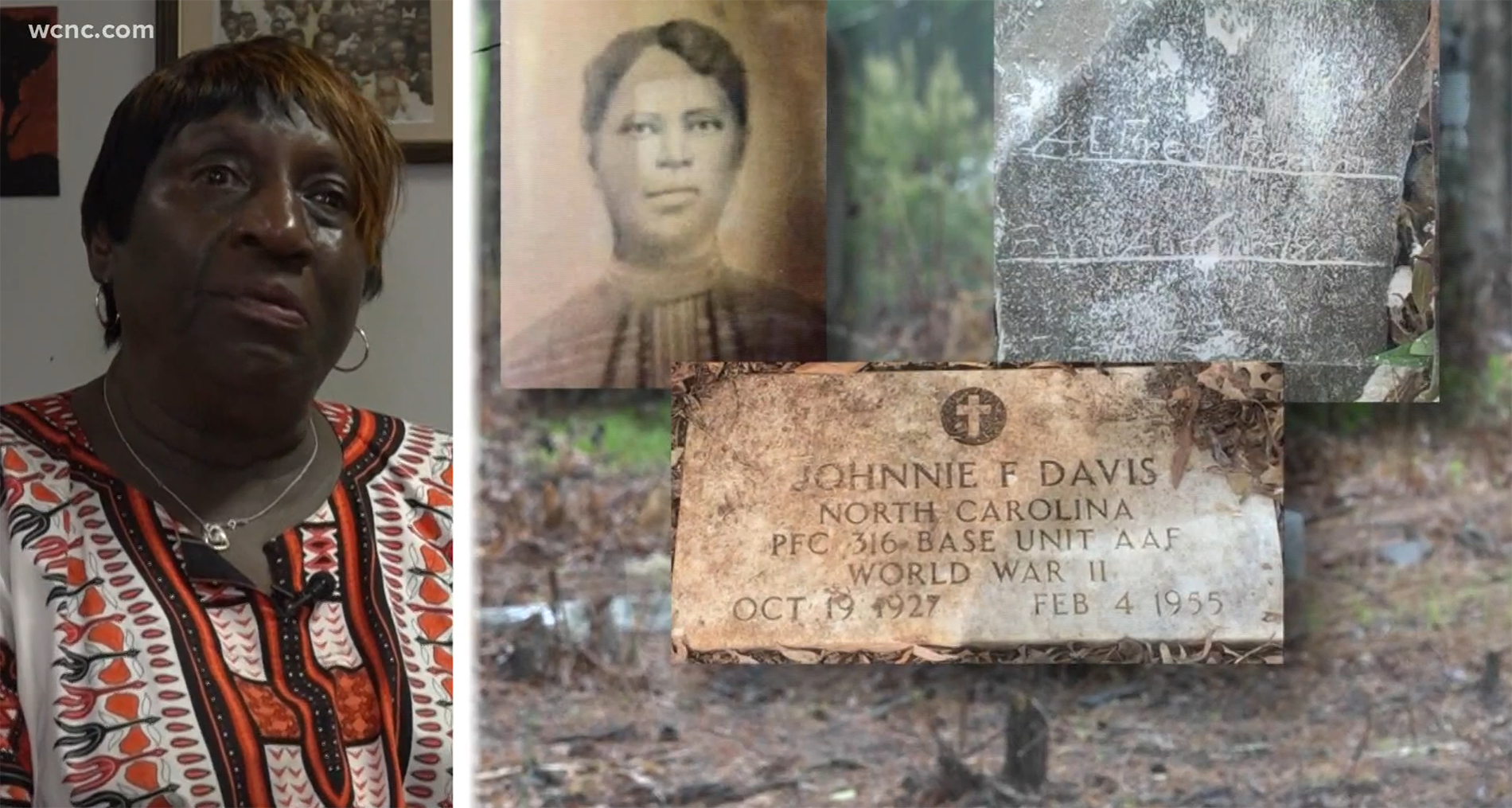

“I had never known where my great-grandmother was buried,” said 74-year-old Carol Smith, a member of Poplar Springs Missionary Baptist Church in Anson County, N.C. “I used to go to my grandpa’s house, and I saw this picture of her in one of his rooms. When I walked out to where she was buried, it just did something to me.”

She found her great-grandmother’s grave marked with a small rock with her name: Ressie Burns Brewer. Through a project to revitalize the original overgrown cemetery at her church, she discovered Ressie died at age 27 of tuberculosis.

“It may not mean a lot to some people, but to me it does,” she said, adding that honoring every person buried in the Poplar Springs Missionary Baptist Church Original Cemetery is personal.

Carol Smith

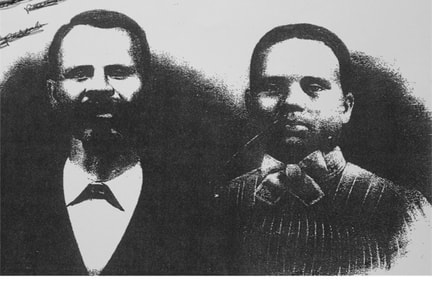

The cemetery has been the resting place for more than 170 Black residents of the surrounding area since 1876. The land for the original cemetery was donated to Poplar Springs Missionary Baptist Church in the late 1800s by Elizabeth “Lizzie” Turner, a formerly enslaved person whose parents, Rit and Grit Clark, were enslaved and brought to North Carolina.

Lizzie was enslaved on the Turner plantation. After she was freed, Mary “Polly” Turner, daughter of Jasper Melchor Turner, deeded the land she inherited from him to Lizzie.

Henry and Lizzie Turner

With this deed, Lizzie chose to donate the land to Poplar Springs Missionary Baptist Church. There, a log cabin — the original church — and the original cemetery were built. Later, the land was willed to Polly Turner Burns, Lizzie and Henry Turner’s daughter. The will “required that Polly or her progeny never sell the land,” ensuring the church and cemetery would remain in the family for years to come.

The log cabin no longer exists and has been replaced with a church building still used by congregants today. The original cemetery served congregants for about 100 years, and today, a newer cemetery is located closer to the church. Over the years, the original cemetery became overgrown with plants and trees, so that three years ago it was hardly visible.

“To me it was like a forest,” said Smith, who grew up in the church and visited the cemetery as a child. “So much growth had taken place among all the stones. I just couldn’t rest on the inside. I just could not rest, knowing those ancestors had contributed so much to society, and the place they were made to rest had just grown up like that.”

Most of today’s Poplar Springs congregants did not even know the cemetery existed when she started this project. Neither did members of the surrounding community.

“Years ago,” Smith explained, the area surrounding the cemetery was purchased and made into a dirt track for recreational dirt bike racing. And because the cemetery itself was so overgrown, it was hidden behind recreation, becoming even more inaccessible and overgrown. “After a while, it just gets forgotten.”

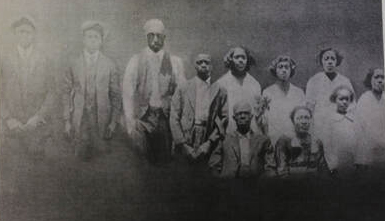

Will Ingram and family

Over the past three years, thanks to the work of Carol Smith, Victoria Matlock, Margaret Price, Julia Lasure and quite a few others, the original cemetery has been revitalized, memorialized and historically certified by the government. Because of this work, Poplar Springs Baptist Church Original Cemetery never will be destroyed or purchased by outside parties, and the histories of its residents are now easily accessible in an online database that continues to grow.

In 2020, when Smith started the project to revitalize the original cemetery, she found some graves hidden under overgrown plants, others eroded or destroyed due to weathering, and some graves “nowhere to be found.” She hoped to clean the cemetery to make the graves more identifiable, then work on detailing the history behind them.

“I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know where to start,” she said. This is where Victoria Matlock and Margaret Price came in. Smith volunteers at the Burnsville Recreation and Learning Center in the area, and a fellow volunteer connected her with Matlock, who is part of the Grave Hunter’s society.

Matlock and Price were the lead researchers for the grave sites, going through the cemetery to discover graves (some headstones had been displaced or were missing), taking photos of graves and transcribing the writings on them. They also conducted interviews with residents in the area and went through the available written histories of cemetery residents to document as much information as possible on the people buried there.

“The first thing we did was document some of the people buried there with as much information as we had on the stones,” Smith explained. “There were over 200 different stones.”

Julia Lasure

After this work, Julia Lasure was called to catalog the “important historical value this project has and will continue to have,” Smith said. To record the cemetery’s history and find a way the “history could live on,” Lasure developed an archival-like website that can be referenced by community members or researchers and is continuously being updated as more information about the cemetery is discovered.

At the time of this project’s completion, Lasure was a sophomore history major and is now an alumna of Wingate University, having graduated with a history major and political science minor. In the fall, she will begin graduate studies in public history and believes this project made a huge impact on her confidence to pursue this field.

She was invited into this project by David Mitchell, associate professor of American history, and assisted in her archiving by Richard Carney, Wingate public history professor and archivist.

For Lasure, this project had tough beginnings. “Going into this project, it was during the pandemic. The first time I went up there I actually got into a car crash. Someone hit me from behind and totaled my car. I was like, ‘Am I ever going to get to this project?’”

This did not stop her. In fact, Lasure jumped right in as soon as she could.

“I had never done anything like this before, so it was scary,” she recalled. “I had just taken a public history class the semester before (with Carney) and I thought, ‘Let’s create a website.’ We’ll make this a public history thing, so people won’t only know it in terms of the community. It will be known outside of the community.”

Along with website, Lasure got the opportunity to meet with some of the congregants and community members who taught her more about their personal connections with the cemetery.

“Doing the oral histories was the best part for me,” she said. “We tend to think of cemeteries and history as very far-off things. It makes it very real when you get to hear what people’s connections are to these places.”

Carol Smith and Julia Lasure

Lasure wanted to ensure that throughout the project, she amplified the voices of the Black community members. It was important for her that as their project discovered, remembered and memorialized the lives of those buried, it recognized the systematic racism that has occurred in the community.

“Obviously, I’m white, and it’s a Black cemetery, so I wanted to be very meaningful in my work,” Lasure said. “I wanted to make sure I was getting the actual voices of people who were connected to the cemetery and make sure I wasn’t taking over, but that it was done by the community who were going to be the ones impacted the most.”

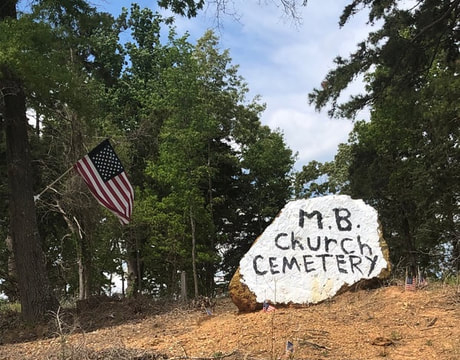

Entrance to the cemetery

Today, the Poplar Springs Missionary Baptist Church Original Cemetery is more clearly marked than it has been for years, but it is still a work in progress. Smith recently put a flag at the entrance but says the location still is not accessible, as the entry point is a hill that was created when the dirt track surrounding it was built.

But so far, all the work has been done on a tight budget, Lasure said. “We didn’t have much money coming in, so all of it was community-based with donations and volunteers from the community.”

The website she created had to be done on a free trial because there were no funds to purchase an internet domain.

“My dream is to have an educational place here in Burnsville with African American history” Smith said. She is currently trying to raise $90,000 to purchase land so generations of young people in the future can learn about the local history of African Americans, including their ancestry as it relates to the cemetery.

When asked about the project’s challenges, Smith said, “The most challenging part is now. Getting the knowledge out and uniting people. Taking the opportunity to look back into history and learn from that. It has been hard for me to do because this is uncharted territory for me. I’ve never done this before.”

Although there’s more to be done, the Poplar Springs Missionary Baptist Church Original Cemetery is more than just a space where the dead are resting. It is a collection of lives throughout history who have something to say. Smith and Lasure want others to listen.

Related articles:

Filmmaker searches for vanished Black graves in Canadian cemetery

Of church cemeteries, pulpit committees, crafts and sweet potato casserole | Opinion by Chris Ayers

At Salem, a reminder the Puritans were Christian nationalists too | Opinion by Joe Westbury