Sunday morning is becoming an increasingly divided time in America.

“If Sunday morning was the most segregated morning in American life, it may also be one of the most politicized hours in American life, implicitly or explicitly,” said Bill Leonard, professor emeritus of divinity at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Bill Leonard

Faith-based political movements that coalesced in the 1980s and now culminating with the Trump-evangelical alliance have fueled the partitioning of Christians along political lines, said Leonard, an expert on church, Baptist and American religious history.

“The whole environment inside and outside the church is so politicized that it’s understandable people would choose churches that parallel their theology and their politics,” he said.

Research bears out the trends experts like Leonard have been tracking for years.

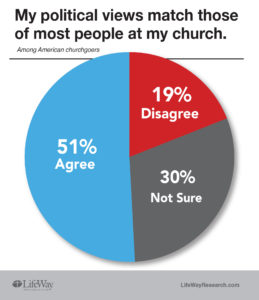

LifeWay Research published a study this week that found many Protestants want to worship with people who share their political beliefs.

“America has become increasingly divided by politics in recent years,” the research group said in an online summary of its study. “So have its Protestant churches.”

More than 1,000 Americans who attend services at least monthly were surveyed. The project found that 46 percent agree with the statement, “I prefer to attend a church where people share my political views.”

Forty-two percent disagreed, and another 12 percent were unsure, according to the article.

However, 57 percent of those ages 18 to 49 agreed with the statement, as did 39 percent of those 50 to 64, and 33 percent of churchgoers 65 or older, LifeWay Research reported.

Men, at 51 percent, were most likely to agree. Among women, it was 43 percent.

Methodists led the way in agreeing with the sentiment, at 57 percent. Non-denominational Christians and Baptists followed close behind, at 51 percent and 49 percent, respectively.

But the mixing of politics and religion is nothing new, Leonard added.

Billy Sunday, a popular evangelist during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was famous for getting saloons shut down in the towns where he preached.

And the Baptist pastor and early fundamentalist J. Frank Norris of Fort Worth, Texas, famous for shooting and killing a man during an argument, was inclined to describe opposing political and cultural beliefs as “devils,” Leonard said.

However, the pace at which politically motivated church selection seems to be advancing may also be in part due to the decline of denominationalism, Leonard said.

“When the denominational system was more intact, they may have tried to mediate some of that,” he said. “You had people agreeing on denominational identity, which kept their political identity in check somewhat.”

It helped Christians on the left and right could overlook differences on racial and social-justice issues while remaining in fellowship politically.

“In the 60s, progressive Southern Baptists were always frustrated because the convention didn’t take what they thought were prophetic stands on social-gospel issues and the war in Vietnam,” Leonard said.

“And on the right, members thought the denomination was selling out on matters like church-and-state separation and no prayer in schools.”

The seeds of the shift toward today’s polarization over politics could be seen even then across different denominations.

“It’s been evolving,” he said.