The nation’s debate over capital punishment took an unexpected turn Sept. 8 when the United States Supreme Court intervened in a Texas case where the man sentenced to die wanted his pastor to hold his hand while he drew his final breath.

Under the policies of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, clergy may be present for executions but may not touch or interact with the inmate inside the death chamber.

John Ramirez challenged that policy and for now has won a stay of execution while the Supreme Court hears a full presentation on his case this fall. Notably, Ramirez has not asked the court to stop his execution, only to allow his pastor to hold him and pray for him while he receives the lethal injection.

This case turns more on questions of religious liberty than on the ethics or morality of capital punishment.

The nation’s high court rarely intervenes in death row cases, but most of those last-minute appeals are to overturn the death sentence itself. But this case turns more on questions of religious liberty than on the ethics or morality of capital punishment.

Of late, the Supreme Court has found favor with cases about the free exercise of religion, one of two prongs of the First Amendment’s religious liberty protections. The other prong forbids establishment of any religion.

To add further irony to the moment, evangelical conservatives are among the most ardent advocates of nearly unlimited free exercise of religion — such as allowing churches to gather indoors despite public health warnings during the pandemic or supporting a baker who refuses to make a cake for a same-sex wedding — but also are among the last holdouts in American culture supporting the death penalty.

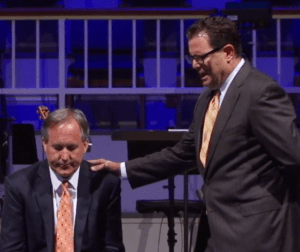

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton — an ardent advocate of religious right causes — found himself defending the state’s position that denies pastoral care to a parishioner in a time of dire need.

Dana Moore

USA Today reported that Ramirez’s attorney told the Supreme Court that the Texas policy required the pastor, Dana Moore of Second Baptist Church in Corpus Christi, to “stand in his little corner of the room like a potted plant” and that “if he even breathes through his mouth, the warden may declare that” the pastor is violating the state’s policy by “trying to utter prohibited words of prayer.”

Texas officials cite security concerns as a reason for clergy not being able to interact with inmates in the death chamber.

In court filings, Paxton argued: “That a state may not impose policies coercing an inmate to do what his religious (tenets) forbid does not mean that it must accede to his every religious demand. By design, prisons impede inmates’ freedom to behave as they might wish, which, necessarily limits some of their religious behavior.”

In 2015, Doug Page (right), pastor of First Baptist Church of Grapevine, Texas, prays over Ken Paxton during a church service.

Ramirez, now 37, was convicted of a 2004 murder at a Corpus Christ, Texas, convenience store, where he fatally stabbed Pablo Castro, a store clerk. Ramirez was a 20-year-old when he and two others confronted Castro outside a market in search of money to buy drugs, according to the Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Ramirez beat and kicked Castro and stabbed him 29 times with a 6-inch serrated knife. The three left with $1.25.

Ramirez fled to Mexico, where he evaded arrest for three-and-a-half years. He was tried and sentenced to death in 2008.

Texas is one of 27 states that still allows capital punishment and since 1977 has executed five times as many people as any other state in the union. Blacks and Hispanics make up 70.3% of the Texas Death Row population. Most Death Row offenders will spend 10 years there awaiting execution.

After his conviction, Ramirez was transferred to Death Row at the Allen B. Polunsky Maximum Security Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. At the time, BNG columnist Michael Chancellor led mental health services at that unit.

“John Rameriz and I were at the prison at the same time, but while I oversaw his care, I have no particular memories of interacting with him, which likely meant he was not a problem offender with which we dealt on a regular basis,” Chancellor said.

“It is worth noting the Texas Department of Criminal Justice strongly supported faith-based ministries and their work in the prisons of Texas because real spiritual transformation always translated into less recidivism,” he added. “That is important when one does prisons on the cheap.”

In fact, according to other news reports, Ramirez met his pastor, Moore, when Moore visited him on Death Row in 2016.

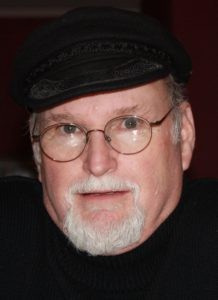

Michael Chancellor

Chancellor finds it ironic that the Ramirez case has drawn national attention at the same time Texas Gov. Greg Abbott just signed into law the most restrictive abortion prohibition in the nation — “because, well, Texas is pro-life, pro-guns, and pro-God, and not necessarily in that order and without any seeming contradiction between those three.”

Chancellor has written previously for BNG about why he opposes the death penalty, but realizing it remains the law of the land in Texas, he believes for now — as illustrated by cases like Ramirez’s — that the Texas Department of Criminal Justice should carry out the state’s laws “with compassion and respect for all. Death Row is not a slaughtering plant dealing with nameless animals big and small. It is a final destination for men and women who have been judged by the courts of Texas (sometimes wrongly) of unspeakable crimes against others.

“If there is still a place in Texas for capital punishment, it needs to be done with humanity and respect. Not because of who the offender is, but because of who we are. Having said that, the presence of this offender’s pastor in the execution room is appropriate — the under-shepherd with the sheep who is surrendering his life for his crimes.”

USA Today and Christianity Today reported that Moore, the pastor, has said: “The power of human touch is more than just physical. It’s the way God created us. When I pray with people, I put a hand on them. When I go to the hospital, I hold the person’s hand. It’s what we do. It’s how we do things. And that’s what John wants me to be able to do. To have me touch him. To have that support. To have that type of blessing.”

Although novel, Ramirez’s case is only the latest in a string of challenges to Texas policies related to spiritual care at the time of an execution. Two of those cases have involved questions of who may be the pastor or spiritual adviser in the death chamber and whether the condemned prisoner has any say in choosing the last person to stand beside them.

Related articles:

Final vote sounds the death knell for capital punishment in Virginia

The death penalty is dying a slow death; it’s time we pull the plug | Analysis by Stephen Reeves

What I learned working in a Texas prison: Retribution, not reformation | Analysis by Michael Chancellor