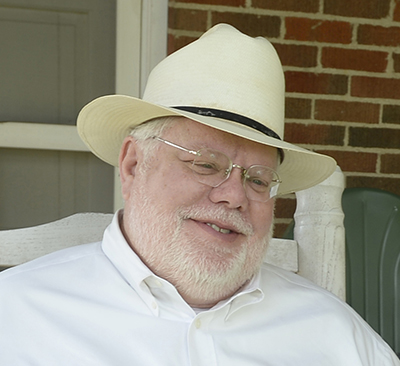

Kyle Childress doesn’t look like a dangerous radical. If Childress, pastor of Austin Heights Baptist Church in Nacogdoches, Texas, let his neatly trimmed white beard grow out a bit, he would make a passable Santa Claus.

And when he pushes his ever-present straw hat back on his head, props up his feet and launches into a story, he easily could fit right in with the spit-and-whittle crowd on the downtown square of the small East Texas town where he has ministered for a quarter-century.

But listen to those stories very long, and you’ll hear his points of reference. Martin Luther King Jr. Will Campbell. Clarence Jordan. Stanley Hauerwas. Wendell Berry. And Jesus — don’t forget Jesus. After all, taking Jesus seriously has been getting Childress into trouble for years.

It led him to become the first white member of a historically African-American ministerial alliance. It prompted prayer vigils for peace in the days leading to U.S. military involvement in Iraq. It inspired Austin Heights to launch a ministry to people living with HIV/AIDS, begin a local chapter of Habitat for Humanity, extend hospitality to environmental activists protesting construction of the TransCanada Keystone XL Pipeline and take unpopular stands supporting women in ministry.

Taking Jesus seriously provided the foundation for what Childress calls “a good fit” between a pastor and a small congregation of East Texas Piney Woods mavericks who don’t mind being challenged — at least most of the time.

Taking Jesus seriously provided the foundation for what Childress calls “a good fit” between a pastor and a small congregation of East Texas Piney Woods mavericks who don’t mind being challenged — at least most of the time.

“They already had this reputation — and kind of a habit — of being counter-cultural,” Childress says. “Now sometimes, a church can be counter-cultural just because they like being counter, not because it’s the gospel. But it’s something you can work with. A pastor can go in a church and help folks know that sometimes what we have to say, and who we are, and what we’re called to be goes against the stream. They already had that in their DNA.”

Childress grew up in Stamford, a small West Texas town southeast of Lubbock. As a child in the ’60s, he recalled hearing TV reports about civil rights protests.

“I remember asking — I don’t even know where the question came from — ‘Where are the white Christians? Where is the white church?’”

As a student at Baylor University, those early questions resurfaced when he read Christian ethics, church history and theology.

“I kept asking, ‘What did the black church know that the white church in the South missed out on?’ And that led me to ask a lot of other questions about poverty and other things. And a lot of the people who were talking about this stuff took seriously Jesus and the Sermon on the Mount,” Childress says.

That’s when he realized the starting point makes a difference when interpreting the Bible.

“Most of the people I was reading started with Jesus. The black church talked a lot about Jesus — partly because a people who had a history of getting lynched recognized their connection with Jesus in Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, who got lynched on a cross.

“If you start hanging around Jesus a whole lot, it raises lots of questions — about violence and war, poverty and wealth, and caring for God’s earth. Now, I’m not saying it gives you every answer, but it sure raises a lot of questions. I wanted to be a pastor who helps a church, a community of faith, ask those kinds of questions.”

Not every community welcomes hard questions, he discovered. As a student pastor in Central Texas, his early attempts at creating dialogue on race prompted hostility and threats.

During a difficult time, Childress found guidance from a long-distance mentor. After reading The Glad River, Childress wrote a letter to the book’s author, Will Campbell, in care of the publisher. That began an ongoing correspondence and friendship between the young minister and the civil rights activist/iconoclastic Baptist preacher.

“I got a great letter — a pastoral letter — from Will Campbell encouraging me, telling me to hang in there,” he recalls. “He told me to love those people. Be a pastor. Don’t demonize them. Just because they disagreed with me on race, that doesn’t mean they’re evil people. They’re just people.”

“I got a great letter — a pastoral letter — from Will Campbell encouraging me, telling me to hang in there,” he recalls. “He told me to love those people. Be a pastor. Don’t demonize them. Just because they disagreed with me on race, that doesn’t mean they’re evil people. They’re just people.”

In time, Childress accepted an internship with Texas Baptists’ Christian Life Commission, while pursuing studies at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas. Later, he moved to Atlanta and become an intern with the Baptist Peace Fellowship of North America. In Atlanta, he lived with the Community of Hospitality, an intentional Christian fellowship, and worked with homeless people.

After one year in Atlanta, he moved to Louisville, Ky., to complete his master of divinity degree at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. At Crescent Hill Baptist Church in Louisville, he met Jane Webb, and they married in 1988.

About that time, he learned from a friend in Fort Worth that Austin Heights Baptist Church in Nacogdoches was seeking a pastor.

Five families — all with ties to Stephen F. Austin State University — started Austin Heights in 1968, primarily because their attitudes about race and opinions about the escalating war in Vietnam made them feel out of place in other local churches. The congregation’s historian, Archie McDonald, noted since its beginning, Austin Heights “has been a gathering for lost sheep, black sheep, burned-out and beaten-up sheep, with a few old goats thrown in as well.”

In January 1989, the search committee at Austin Heights contacted Childress, and he and Jane traveled to Nacogdoches in April and June — not only to meet the church members and preach in view of a call, but also to meet Larry Wade, pastor of Zion Hill First Baptist Church, an African-American congregation that has a long-term relationship with Austin Heights.

In Austin Heights’ 40th anniversary history, The Amazing Grace Baptist Church, member Bob Carroll offered a candid assessment of his pastor: “He was somewhat inflexible when he first arrived, creating some degree of friction with various members, but he mellowed over the years. His preaching is thoughtful and insightful and shows evidence of much work on his sermons. He was often controversial, and we lost a few members during the early years who were not as tolerant as most of us.”

Childress ruffled a few feathers when he joined not only the local ministerial alliance the other white pastors attended but also a ministerial alliance that previously had been entirely African-American.

“It was just about showing up — not trying to run anything, not trying to be in charge, not being the speaker,” he says. “Do that consistently over time, and people learn who you are, and you develop friendships.

“You learn to listen, and you hear different perspectives. … Sometimes, you can go to the white ministerial alliance, and say ‘How are you?’ to somebody, and they’ll say, ‘Busy.’ And the meeting lasts an hour — exactly an hour — because people have other appointments, and they are in a hurry to leave. It’s very task-oriented.

“If I go to the [African-American] Interdenominational Ministers’ Alliance, and ask, ‘How are you?’ they’ll say, ‘Blessed.’ And we may be there two or three hours. We may eat together. It’s about fellowship. It’s about friendship. It’s about mutual encouragement. … My closest friends who are clergy are black pastors.”

Childress raised considerable consternation in the community when he led Austin Heights to begin a ministry to people with HIV/AIDS in 1991. The congregation provided transportation for patients receiving care 190 miles away in Galveston, offered space for a weekly support group and held a Service of Hope worship experience for people affected by AIDS. Childress and members of Austin Heights formed the East Texas AIDS Project, which grew into Health Horizons.

At the time, Austin Heights drew only 30 to 40 people for worship on an average Sunday. Some weeks, one-third of the worshippers were gay men with AIDS.

“We were trying to turn things around. But a sure-fire way to death in the church is to focus on survival. The way to thrive as a congregation is to get your mind off yourself and be willing to die. And, lo and behold, you find life,” Childress says. “You don’t exactly grow a church doing AIDS ministry. … But the gospel irony was that we did start growing.”

The AIDS ministry attracted some new members to Austin Heights. It also drew angry letters, irate phone calls and protesters from a fundamentalist sect in nearby Mount Enterprise, led by Pastor W.N. Otwell.

Some of those same protesters returned when Childress invited his longtime friend, Nancy Sehested, to preach a revival at Austin Heights. Protesters called Austin Heights a “whore church” for allowing a woman in its pulpit.

“The irony of that was that their protesting probably doubled our attendance,” Childress says. People who saw the vulgar signs the picketers displayed figured if they opposed Austin Heights, the congregation must be doing something right, he said.

In recent years, Austin Heights has grown to about 100 in average weekly attendance. In 2013, the church called its first associate pastor — Sarah Carbajal, a graduate of Baylor and the university’s School of Social Work and Truett Theological Seminary who grew up in Nacogdoches.

She will preach all summer when Childress takes a sabbatical to read, write and study — something his congregation values and encourages.

“They expect substance in the pulpit, and they also give the time to prepare substance.”

They also allow Childress to spend time away twice a year with five pastor-friends who call themselves “The Neighborhood,” inspired by a long-term community of friends in The Glad River. The six ministers spend several days together talking, reading, praying and encouraging each other.

“The Neighborhood has helped keep me alive,” Childress says, noting Austin Heights’ church council always remembers to add the group’s twice-annual gatherings to the church calendar and prepare for their pastors’ absence.

While the stands he has taken through the years sometimes have been unpopular in his community, Childress earned credibility over the long haul and through “hundreds of conversations in the grocery store.”

“A lot of pastoral work in the wider community is just showing up” for PTA meetings, Boy Scout events, high school ballgames and student recitals, Childress says.

“After 25 years, if you are involved, and you genuinely listen to people, you become a pastor to them, more and more in the wider community.”

Like some pastors, Childress maintains an open-door policy, inviting people to come to his office and “vent” if they need to do it. Unlike most ministers, he also maintains an open-porch policy.

Like some pastors, Childress maintains an open-door policy, inviting people to come to his office and “vent” if they need to do it. Unlike most ministers, he also maintains an open-porch policy.

Childress proudly displays a certificate declaring his charter membership in the National Association of Porching. Several years ago, when he was away from Nacogdoches on sabbatical, the church built a back porch onto the Childress home.

“In the office, it’s counseling. On the porch, it’s friends talking. That’s why you have a porch,” he says.

It offers Childress one more place to connect with people — the kind of ministry he loves.

“I believe in the personal touch. It’s not for everybody, but for me as a pastor, it’s about face-to-face incarnational ministry.”

Childress cherishes community, and he seeks to create a climate of mutual caring at Austin Heights.

“I want to be in the kind of church where, if you were to walk in the door and accidentally step on the toes of one person, everybody would holler, because they are so connected to one another in Christ.”

That doesn’t mean everybody agrees, he adds. It means they love and respect each other enough to disagree and grow from the experience.

“It’s not just me. It’s about us. Christian discipleship is always ‘us.’ It’s personal, but it’s always in community,” he says.

“Within the community of faith, we have arguments, we have disagreements, and we hammer things out and debate and pray and read the Bible and argue some more. That’s the way it’s supposed to be. … We’ve built up enough trust so that disagreeing with each other has nothing to do with whether we are brothers and sisters or not.”

— This article was first published in Herald, BNG’s magazine sent five times a year to donors to the Annual Fund. Bulk copies are also mailed to BNG’s Church Champion congregations.