Fifty years ago, on Dec. 17, 1974, I had my initial interview at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky. With one semester to go toward completing the Ph.D. program at Boston University School of Theology, I mailed my resume to assorted religion and history departments across the country. (I still have a file full of rejection letters, some of which were from folks who later became close friends.)

Then one December afternoon, the red dial telephone in our parsonage at First Community Church, Southboro, Mass., rang and I answered. The caller was William Hull, provost at SBTS, inviting me to the Dec. 17 interview for a position as assistant professor of church history with a specialty in American Christianity. It was the only interview invitation I received.

Traveling to Louisville and ensconced in a dorm guest room and picked up for lunch by church history professors E. Glenn Hinson and Morgan Patterson, who took me to the Oriental House restaurant. Only later would I learn that was one of Professor Hinson’s favorite eating places, frequented many Wednesdays by the church history colloquium group of faculty and doctoral students, a treasury of friendship, dialogue and debate. My friendship with Glenn Hinson began over Chicken Chow Mein.

Next came an interview with the faculty search committee whose members questioned me about my education, research, dissertation, approach to classroom teaching and four-year pastoral ministry at a New England church founded in 1865.

At the end, Christian ethics professor Henlee Barnette asked with a wry smile: “We’ve had several native Texans on this faculty, but they’ve never lasted very long. Do you think you can?”

I told him that like most any Texan, I’d give it my best shot. He laughed, and another long friendship took shape. (Hinson and Barnette were among a group of progressive professors who helped facilitate Martin Luther King’s 1961 chapel sermon at SBTS.)

Returning to Massachusetts, I awaited “word from Southern.” It came with Provost Hull’s early January invitation to return for a full faculty interview and vote on my candidacy. The vote went well, and I was offered the position. Candyce and I moved to Louisville in June 1975, accompanied by our 9-week-old daughter, Stephanie. (I “lasted” at SBTS 17 years, until it became impossible to remain.)

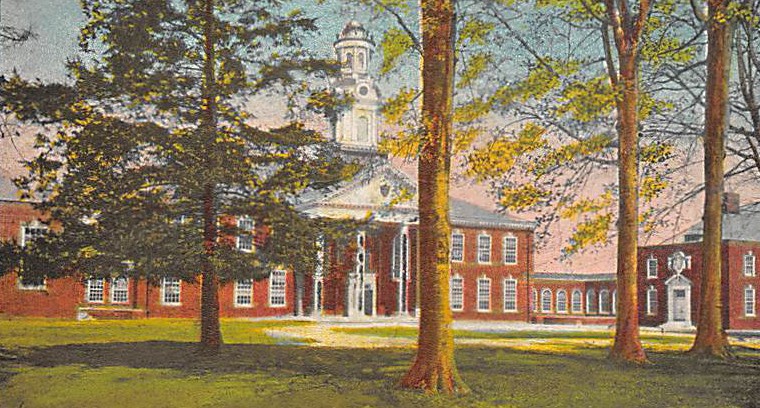

The seminary was founded in 1859, just 14 years after the formation of the Southern Baptist Convention, a denomination born of divisions over slavery that split Baptist missionary cooperation North and South, and ultimately the nation. The four founding faculty members were outstanding theological educators, educated at Harvard, Princeton Seminary, and the University of Virginia. All four owned slaves.

The school’s recent investigation of the slavery era notes, “The seminary faculty supported the righteousness of slaveholding and opposed efforts to limit the institution.” It is a legacy that still haunts the SBC and many of us who were raised therein.

In January 1975, I was 28 years old. Southern Seminary provided a context that informed my teaching, learning and listening for learning to teach. Where the classroom was concerned, I went there “as green as a cabbage patch,” as one of my Massachusetts church members described my first pastoral experience. A half-century later, and 32 years from my departure from the school, I’ve tried to reflect on certain lessons I learned in that process, lessons formed in the context of classroom and culture, spiritual experience and denominational conflict.

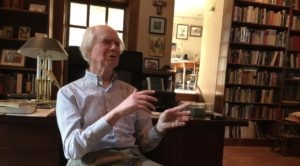

Of the many mentors in my life, none formed my identity as would-be historian, teacher, Christian and, yes, Baptist, more than E. Glenn Hinson. And I am not alone. Multiple student and faculty generations know and admire him as historian, scholar, mystic, dissenter and mentor extraordinaire.

Now in his 94th year, Hinson is a Baptist who gravitated to the fathers and the mothers of the early church, delighting in their insights, struggles and dysfunctions. As one student observed: “You have to take him seriously. Hell, he can even read Latin.”

He taught us we belong to those ancient people and they to us and no matter how hard we try to act as if all our dogmas came pristinely from the New Testament, we’d better tarry in the early Christian centuries if we want to understand ourselves.

From our first meeting half a century ago, Glenn has modeled to me and countless others the best of the professorial arts. A historian’s historian, he understands such studies are important, not only because they inform our knowledge of the past, but also our sense of who we are in the present.

He is, pure and simple, a crafty historian who knows how to push us, challenge us, shape us, exacerbate us and compel us to come to terms with pieces of history, and pieces of ourselves, we’d just as soon keep buried deep and wide. At SBTS I saw him do it often in the infamous weekly colloquium, that Wednesday gathering of faculty and the marvelous church history grad students.

There the academic territory was staked out by one or more students, and then Hinson would ask a question, barely able to disguise what Phyllis Rogerson Pleasants Tessieri called “that little smile,” disarming us all. The question was raised; the thesis challenged; the dialogue off and running. The historian’s craft was typified by the crafty historian.That’s one of the great lessons Glenn has taught us over the years.

Yet Hinson’s vocation as teacher is inseparable from his holistic spirituality, articulated in his many books including A Serious Call to a Contemplative Lifestyle. On April 18, 1961, a mostly unknown Trappist monk named Thomas Merton wrote in his journal:

“Hinson’s vocation as teacher is inseparable from his holistic spirituality.”

A good group from the Southern Baptist Seminary here yesterday. Very good rapport. I liked them very much. An atmosphere of sincerity and understanding. Differences between us not, I think, minimized. Dr. Hinson, the church history man, a good and sincere person, with some of the other faculty members, will come down again. We will talk, perhaps, about the church. I am glad they will come.

Directly and indirectly, Hinson has served as spiritual guide to innumerable individuals, articulating and exemplifying the necessity for and process toward cultivating the inner life. He connected us to Trappists at Gethsemani and Benedictines at the St. Meinrad Abbey, contemplative environs and monks who made profound impact on my own life.

Through it all, E. Glenn Hinson personifies the dissenting tradition of the Baptists. He refuses to allow others to define his own sense of Baptistness and his conscience has gotten him into all kinds of good trouble.

In an 2019 essay titled “Are We Finally Ready to Learn from Glenn Hinson, One of our Baptist Prophets,” SBTS Ph.D. history graduate Alan Bean provides a masterful account of Hinson’s response to a 1980 Religious Roundtable speech by then SBC president and evangelist Bailey Smith who asserted that “God almighty does not hear the prayer of a Jew.”

The first Baptist voice raised against that antisemitic diatribe was that of Hinson in “An Open Letter to Bailey Smith” published in the Western Recorder. In words I never can forget he concluded: “Statements such as this one are the stuff from which holocausts come.”

All kinds of religio-cultural hell promptly broke loose, not just in the media, but in the churches. SBTS was flooded with complaints and some administrators wanted Hinson “disciplined” for his action. But he was right, and he said so. I was away on sabbatical, but I called him just to say how much his courageous words and witness meant to me. I knew even then that it was at the center of his being. It still is.

In the 50th year of that friendship, I think Glenn’s response to Smith’s remarks and the Religious Roundtable itself anticipated the early stages of a Christian nationalism now rampant in American culture and American Christianity. These days, the language of Christian political hegemony seems to suggest that “God Almighty does not hear the prayer of a (fill in the blank),” with non-Christian communions tolerated by a certain kind of fully privileged Christianity. In 1980, Hinson did not know what lay ahead, but he saw the dangers clearly and said so.

In a recent phone conversation, he expressed thanks for our friendship, adding, “because you know how to make trouble like I do.” I responded, “And you taught us how!” Had we talked a bit longer, I suspect he would have gotten “that little smile” and added, “Don’t blame me, Bill. Blame Jesus.”

Right again, Dr. Hinson, right again.

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Are we finally ready to learn from Glenn Hinson, one of our Baptist prophets? | Opinion by Alan Bean

Why all Christians, not just Baptists, are profoundly indebted to Glenn Hinson | Opinion by Doug Weaver

Hinson-Merton friendship continues impact on Baptist spirituality