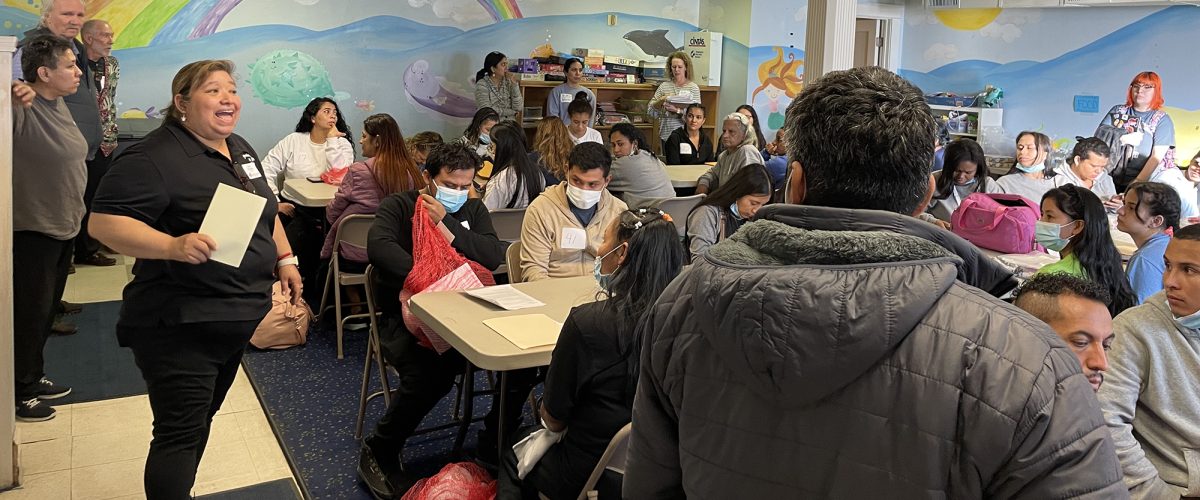

Even though I graduated from both high school and college in New Mexico, my Spanish is pretty bad. But I understood clearly what Pastor Isabel Marquez was telling the 52 migrants gathered in a small room at Oak Lawn United Methodist Church in Uptown Dallas yesterday morning.

“Eres libre!” she said to applause from the group. “You’re free!”

The group of young women and men had just arrived on a big white government bus that looked like a prison transport. They had made the last four-hour ride of their homeland security detention to arrive at this 100-year-old church, where they were greeted warmly by a small group of volunteers, including me.

Yesterday, I decided to put my actions where my words have been. I write all the time about the biblical command to welcome the stranger, and I’m part of several nonprofits engaged in that work. But most days I don’t have any skin in the game.

Yesterday, I decided to put my actions where my words have been. I write all the time about the biblical command to welcome the stranger, and I’m part of several nonprofits engaged in that work. But most days I don’t have any skin in the game.

A friend posted on Facebook a need for volunteers to welcome migrants to Dallas on several days, so I signed up to help. The work is coordinated by an interfaith organization that on the day I volunteered brought together Muslims, Methodists, Baptists, Unitarians, Latter-day Saints and Catholics.

When I signed up, I had no idea what I was getting into or that I would need to step away several times to let my tears flow.

This is one of the most meaningful things I’ve ever done in my life.

On this day, I was one of only a few volunteers who had signed up — way too few to manage all that was to come. The business of welcoming migrants is unpredictable, I was told, because volunteers are needed only on days when large groups are scheduled for release. That can be twice a week or it can be twice a month or it can be once every three months.

Yesterday, our new migrant friends came from a federal detention center somewhere in West Texas, a place I never heard of before.

Everyone was clean and clothed, although some barely clothed. One man from Turkey wore too-big sweatpants and a droopy white T-shirt, the only clothes he had. He asked one of the other volunteers if he could get something to wear and the answer, of course, was yes. But first there was paperwork to be done. Always paperwork.

Everyone was clean and clothed, although some barely clothed. One man from Turkey wore too-big sweatpants and a droopy white T-shirt, the only clothes he had. He asked one of the other volunteers if he could get something to wear and the answer, of course, was yes. But first there was paperwork to be done. Always paperwork.

Another young man, Teddy, wore nice jeans with rolled up cuffs but couldn’t keep the pants up on his slim frame. He wanted to know if we had any belts.

Earlier in the morning I had been sorting contributions in the clothing room, and I hadn’t seen any belts there. So I impulsively took off the belt I was wearing and handed it to him. He needed it far worse than I did. And I knew I could buy another and not miss a meal.

Those with something to carry held their few possessions in cheap potato sacks they had been given. At the church, they were allowed to choose new backpacks to carry their few belongings with dignity.

Those with something to carry held their few possessions in cheap potato sacks they had been given. At the church, they were allowed to choose new backpacks to carry their few belongings with dignity.

In a former children’s Sunday school classroom, we all waited. Refugee work involves a lot of waiting. The new arrivals had to wait for their number to be called so they could verify their documentation and final destination. From here, everyone was going to meet their U.S. sponsor — most traveling by plane with tickets purchased by their sponsors that morning.

Amid this waiting, we talked. My job was to offer directions to the restroom and the electrical outlets and to answer random questions with the help of Google Translate.

It was during this time that I met Mohammed, a slender young man from Yemen who wore an infectious smile.

Passing my smartphone back and forth, we carried on a conversation. Unlike nearly everyone else here, he had a friend picking him up. His final destination: Cleveland, Ohio.

Knowing just enough about Yemen to understand it is one of the world’s most dangerous places, I asked why he had fled. His answer was succinct: because Saudi Arabia was bombing his town every day.

A Homeland Security bus delivering migrants to Oak Lawn UMC in Dallas is seen through a Christmas wreath on a door to the church.

I asked what route he had taken to get to the U.S. border, and he spoke this into my phone in Arabic: Beirut, Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Mexico.

He called it “an arduous three-month journey.” No doubt.

About an hour later, the friend who was to pick him up arrived, and I watched as they united and he said farewell to his traveling companions of recent days. A tender and warm moment.

No sooner had they left than I stood at the very same spot and watched a young man reunite with either his parents or his aunt and uncle — I couldn’t be sure which — in a moment that was just like those moving news photos you’ve seen. They were so happy and grateful to be reunited in “libre.”

Everyone standing watching this scene was crying, me included.

This was the easy part of the day. Next, they told me I was needed to be an airport escort.

Oh, my. It all happened so fast I couldn’t say no. And there were no other volunteers.

Soon I found myself on a small bus owned by Catholic Charities and responsible for getting nine Spanish-speaking migrants to various terminals and gates at DFW International Airport.

Have you ever been to DFW Airport? It is enormous, spread out over five huge terminals each with dozens of gates. My charges were to fly out of three different terminals. And we had less than an hour to get the first one to his gate.

Mercifully, I was able to get a pass to accompany my new friends through airport security. Otherwise, none of this would have worked.

I have escorted 100 youth on a choir tour out of the country. I have been responsible for 50 senior adults at airports at home and abroad. That is nothing to suddenly being responsible for getting nine non-English speakers through airport security in a country they don’t know and where they are looked at as possible terrorists and still get some of them to their gates in less than 30 minutes.

Once all the TSA supervisors had been alerted and paperwork processed again, we got to go through the scanners.

My pants were falling down as I lifted my hands in the air for the X-ray image. But that was OK. There were more important things to worry about. I watched as TSA agents carefully searched all nine of the brand-new backpacks. They were business-like but not mean. One spoke Spanish, which helped a lot.

“With everyone else in tow, we made our way through the airport.”

Unlike most Americans traveling through airport security, my companions carried no liquids, no food, nothing that would trip up the scanners. I stood nervously by watching each one get the green light to proceed. It seemed to take forever. More waiting.

Then the race began. Our first drop-off was just a few gates away, which was good because he now had about 15 minutes to make his flight. With everyone else in tow, we made our way through the airport, dropping off one or two and then eventually riding the SkyLink tram to a far-away terminal.

Here’s where my limited Spanish came in helpful once again: “Uno mas,” I said to keep the last four passengers from getting off the tram early. Once there, we raced again to get the next person to his gate on time with just minutes to spare.

With each departure, others in the group offered an enthusiastic goodbye. None of us are likely to see any of the others ever again in this life. We are strangers whose lives intersected for just a moment — but for a life-changing moment.

If you saw the 52 people who got off that motor coach with the narrow prison-style windows, you could imagine any one of them being your neighbor, your coworker, your friend, your child, your sister. These are normal people who bring energy and skill and ambition to their new homeland.

I’m pretty sure none of them were rapists or thugs or bandits. That’s only a scary ghost story told to keep us from seeing ourselves in the faces of migrants.

I’ll keep writing about the biblical command to welcome the stranger, and I’ll keep serving to support local organizations that welcome the world to our doorstep. But I’ll also keep going and volunteering now. The only difference will be that next time, I’m taking friends with me.

This is too great an experience to keep to myself.

Mark Wingfield serves as executive director and publisher of Baptist News Global.

Related articles:

Religious groups step up as DeSantis and Abbott make immigrants pawns for publicity

Who is my neighbor? Reflecting theologically on the migrant crisis | Opinion by Kate Hanch