One afternoon almost 20 years ago, I was sitting in my office at Baylor University when my desk phone rang. Even in those days, I usually ignored it. It was much more likely to be a telemarketer than a student in distress. But, thankfully, that day, I answered.

Thankfully, because after I gruffly picked up, the voice on the phone said, “Hey, Greg. This is Bruce Hornsby.”

Yes, the multi-Grammy-winning pianist, singer and songwriter who was — and continues to be — one of my most important musical lights.

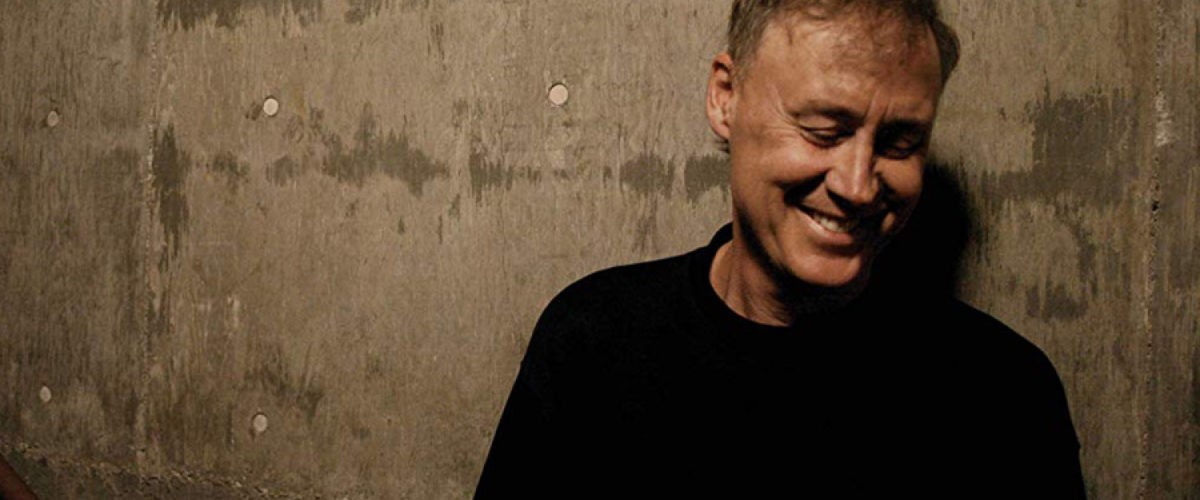

Greg Garrett

It turns out that Bruce was out on tour, and that he was reading my first novel, Free Bird, and he wanted me to know that he was knocked out by it. We kept in touch over the years. I’ve seen him play on a number of occasions. And then, on April 22, Bruce came into my race and film class at Baylor via Zoom to talk about his 20-year collaboration with Spike Lee, about his 35-year career writing songs about race and justice, and about the role of the artist in confronting racism.

Bruce opened our conversation by talking about Nina Simone’s credo: “It’s the artist’s job to reference the time in which we live.” Like James Baldwin’s awareness that the artist is called to witness the world, Bruce has lived into this observation and confrontation from the beginning of his career, calling out both individual racism and systemic racism beginning with his No. 1 single “The Way It Is” (1986), which references both a confrontational man responding to people of color in the unemployment line and to those shaped and misshaped by the harmful stories and practices of our country: the people who can’t buy a job, the little boy who can’t go where the others do because he doesn’t look like they do, the received wisdom that “that’s just the way it is; some things will never change.”

Bruce wanted to be clear that he didn’t believe this was how things have to be. The last line in the chorus is directed to us, the listeners: “But don’t you believe them.” He called for my students to push back against the way things are, against the injustice and unfairness.

In another early song, “Night on the Town,” the title track of his 1990 album, Bruce spoke about how tradition and habit cement us into damaging and even dangerous beliefs: “Said do what your daddy told you/Well I just went out and did that.” It’s easy to believe that if this is the way things have always been done, he told us, this is the right thing to do.

“He called for my students to push back against the way things are, against the injustice and unfairness.”

The song “See the Same Way” from 1998’s Spirit Trail, similarly acknowledges truths that have only become more true in the years since — how hard it is for individuals from different backgrounds to acknowledge the same reality, and the jagged divides in our culture. There’s the acknowledgment of individual racism in this song, but also the ways our racial myths have damaged us all, including his reference to the famous Clark test, where children of all races overwhelmingly identified with a white doll as a standard of beauty. In the song, a dark-skinned girl picks up a doll that “looks just like her” and throws it into the garbage.

The end of “See the Same Way,” Bruce told my class, pulls tropes from Gospel songs and again pushes back against the way things always have been to imagine the way things could be:

I want to be at the meeting

Well, I want to be in that number

When we all see, see the same

See the same way.

Bruce also has dealt with some of our biggest racial myths, including miscegenation and mixed-race relations. My class had noted this as a major issue in American life addressed in films including Birth of a Nation (1915), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), and Get Out (2017).

In his song about the Klan, “Fire on the Cross,“ Bruce included a line about how one of their greatest calls always has been to “keep the dark sons away from our daughters,” while his first collaboration with director Spike Lee came when Lee directed the video of Bruce’s song about mixed-race relationships, “Talk of the Town,“ from 1993’s Harbor Lights.

Like much of Hornsby’s music, it turned out that this song had a personal genesis. Bruce, who was 6’4” and the lone white boy on his high school basketball team, developed many significant interracial friendships on the basketball court. One of his teammates in Williamsburg, Va., dated a white girl for a time — which set off everyone in town, it seemed. The lyrics themselves show a world upturned:

The old town fathers are up in arms

The city council is very alarmed

Cousins and uncles are having fits

Predictors of doom think this is it.

Bruce has continued to make relevant music into the present moment; those who remember him only in terms of “The Way It Is” may not know how that song has been sampled by 20 rappers from Tupac to last year’s “Wishing for a Hero” by Polo G. And on his most recent album, 2020’s Non-Secure Connection, Bruce recorded a stunning new track on race, “Bright Star Cast” with singer Jamila Wood and the legendary guitarist Vernon Reed of Living Colour.

“That song was inspired by the 1619 Project from the New York Times,” Bruce told us. “An alternate way of thinking about American history as shaped primarily by race and slavery.” And, he told us, he was inspired by the “Negro National Anthem,” the hymn “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which is also one of my own formative texts.

“Bright Star Cast” is yet another stunning and powerful song about where we’ve been, where we are and where we want to be. Great art can reinforce the way things always have been, or it can push us toward change. Bruce Hornsby has been reaching out for 35 years to remind me, and, I hope all of us, that the future is where we belong:

I want to be at the meeting.

I want to be in that number.

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. One of his most recent nonfiction books is In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett. His latest book, A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation, is hot off the presses. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.