Invocation — The Whole World Is Waiting, Kate Hurley

The whole world is waiting,

The whole world cries.

The whole world is waiting

For our hope to shine.

For you sweet Jesus

Will make all things right.

The whole world is waiting,

The whole world cries.

You are the God of justice,

You are the God who sees.

You are the God who heals and

Who loves the world through me.

We believe our love can change things.

We will not live silently.

You are the God of justice.

You are the God who sees.

I don’t remember when I picked up this handy mental trick. Sixth grade, maybe seventh?

My first memory of using this technique came during a world geography class. The teacher asked us to memorize the names of European countries’ capitals, most of which I’d never heard before. So I worked at creating a mental association using a random word or fact.

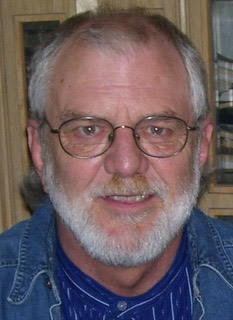

Ken Sehested

To this day, I recall the capital of Bulgaria is Sophia because I came up with the whimsical image of a bull lying on a sofa.

Neuroscientists have dozens of theories and countless technical words to describe how the mind works, particularly how memories are shaped, stored, altered and retrieved. But the basic insight goes back to ancient Rome’s first century statesman-lawyer-orator, Cicero, who wrote: “The eyes of the mind are more easily directed to those objects which we have seen than to those which we have only heard.”

Some of my mental pairings are humorous, like the status of Sophia. But most are not. I recall more than a few Scripture verses because my “mind’s eye” has paired them with specific visual representations. Like the names and/or faces of specific people or historic moments.

I have four faces that arise during Advent. The first, Rosa Parks, is relatively well known in the United States. The others — Ita Ford, Alfred Delp, Antonio de Montesinos — not so much.

Rosa Parks

It was on Thursday, Dec. 1, following the first Sunday of Advent 1955, that seamstress Rosa Parks spontaneously committed an act of civil disobedience (some would say holy obedience) by refusing to give up her bus seat to a white patron in Montgomery, Ala. The following Monday was the first day of what proved to be an ongoing city bus boycott by African Americans in that city. That action ignited the modern Civil Rights movement.

Rosa Parks being fingerprinted by Deputy Sheriff D.H. Lackey, Montgomery, Ala., Feb. 22, 1956. (Public domain image)

Although her action was not preplanned, she had been prepared, as a leader in the local NAACP and two weeks of nonviolence training at the Highlander Center in Tennessee. She and her husband suffered terrible costs as a result.

Two of my favorite quotes from Parks:

“When that white driver stepped back toward us, when he waved his hand and ordered us up and out of our seats, I felt a determination cover my body like a quilt on a winter night.”

And this: “I have learned over the years that when one’s mind is made up, this diminishes fear; knowing what must be done does away with fear.”

Ita Ford

On Dec. 2 1980, Maryknoll Sister Ita Ford and three of her colleagues — Dorothy Kazel, Maura Clarke and lay missioner Jean Donovan — were abducted, raped and assassinated on a lonely road not far from San Salvador by members of the Salvadoran National Guard. Why? Because of these missionaries’ advocacy for the poor during El Salvador’s civil war.

Ita Ford

Shortly before her martyrdom, Ford wrote the following to her niece: “I hope you come to find that which gives life a deep meaning for you. Something worth living for — maybe even worth dying for — something that energizes you, enthuses you, enables you to keep moving ahead. I can’t tell you what it might be — that’s for you to find, to choose, to love. I can just encourage you to start looking and support you in the search.”

Having previously served in Bolivia and Chile, Ford arrived in El Salvador on the day of Archbishop Oscar Romero’s funeral. Romero had been assassinated by members of the Salvadoran military as he raised the Eucharistic host during Mass.

He had become a threat to the country’s dictatorial government for his outspoken opposition to the military’s ravaging violence, particularly directed at the poor. Members of the military had learned “counter-insurgency” tactics under the direct tutelage of the U.S. military, funded by the U.S. administration.

It’s estimated that 75,000 Salvadorans died in that war. One massacre by the military (during the second week of Advent in 1981) took the lives of more than 800 civilians in the small town of El Mozote, including men, women, children, even infants.

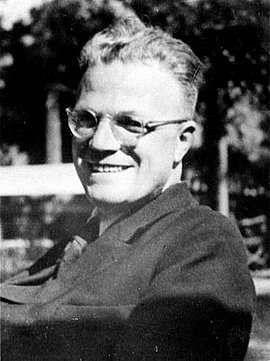

Alfred Delp

Father Alfred Delp, a Jesuit priest in Germany, was arrested, tortured and hanged by the Gestapo on Feb. 2, 1945, for “high treason,” in part because of his work in helping Jews escape Nazi Germany. I associate him with Advent because one of his statements.

Alfred Delp

Writing from his cell during Advent 1944, awaiting execution, he wrote: “Advent is the time for rousing” in order to “wake up to the truth,” followed by “renunciation, surrender,” when we must forfeit “mistaken dreams, conceited poses and arrogant gestures.” Such a rousing “is necessary to kindle the inner light which confirms the blessing and the promise of the Lord. A shattering … that is the necessary preliminary. Life only begins when the whole framework is shaken.”

Under direct orders from Hitler, Delp’s body was cremated and his ashes scattered in an unidentified field. Thomas Merton described Delp’s writings (smuggled out of prison before his execution) as “perhaps the most insightful Christian meditations of our time.”

Antonio de Montesinos

It was the fourth Sunday of Advent 1511 — more than 700 years ago — on the island of Española (modern Haiti and Dominican Republic). Three years prior, three Dominican monks had arrived as Spain’s first missionaries to the territory. One day a stranger appeared at their door. Earlier he had committed a crime of passion, but was now returning — penitent, desiring entrance into the order as a novice — from years of hiding in the mountains.

Antonio de Montesinos

Offering customary hospitality, the monks heard firsthand accounts of Spanish soldiers’ cruel and bloodthirsty treatment of the native Taino people, forcing them to work as Spanish agricultural slaves and gold miners. Whole villages had been plundered. The rape of women was pandemic.

These accounts of Spanish brutality weighed heavily on the friars’ minds. After much prayer and conversation, it was agreed that a protest must be issued. They chose their most eloquent preacher, Antonio de Montesinos, to voice a rebuke.

Montesinos’ text for the day was the clarion call from John the Baptizer, “The voice of one crying in the wilderness” (Matthew 3:3). This voice, Montesinos declared to the gathered colonial authorities attending mass, is that “all of you are in mortal sin and you live and die in it due to the cruelty and tyranny which you practice with this innocent people. Tell me by what right and with what justice do you hold these Indians in such horrible servitude? With what authority have you waged such detestable war, bringing havoc and death never before seen on these people who were living peacefully and calmly on their lands?”

The conflicting emotions of Advent

I’m aware of the difficult pastoral task of leading a congregation through Advent. Many are ready to start singing Christmas carols (and maybe Bing Crosby’s White Christmas and Mariah Carey’s All I Want for Christmas is You) immediately after Thanksgiving leftovers are consumed.

Only Scrooge and the Grinch grouse over holiday tinsel and seasonal cheer. And maybe you’ve seen that internet meme depicting John the Baptist saying, “Welcome to Advent, you brood of vipers!”

“Truth be told, the original Advent was a frightful season.”

Truth be told, the original Advent was a frightful season. Mary could have been stoned to death for her perceived adultery. Multiple angelic appearances in the Gospel stories began with, “Hey, don’t be afraid.” Herod was tipped off about a supposed rival being born, then ordered infanticide of baby boys around Bethlehem. Everyone in Palestine was living under the imperious reign of Caesar, who was publicly celebrated by the grateful Roman populace as “savior,” “lord,” “prince of peace,” who “saved the world” and brought “peace on earth” (by means of ruthless coercion).

According to Scripture, Jesus, too, knew he could mobilize “legions of angels” to prevent his shameful, gruesome execution. He explicitly refused that option.

Two decades ago, I wrote a new verse to “O Little Town of Bethlehem” after peeking through closed curtains from a second story balcony, watching Israeli armored vehicles rumble through that city’s narrow street just below me: “O wounded town of Bethlehem / How sad we see thee cry / Above thy curfewed, empty streets / The belching tanks roll by.”

I do most certainly believe it’s a party, not a purge, to which we are headed in the fulness of time. But our witness to the coming great jubilee of the reign of God lacks credibility without attention to the shadow of death that surrounds us.

The prophet Isaiah is correct in saying salvation’s bright light is coming to those who “dwell in the shadow of death.” The Gospel of Matthew echoes “the people who sat in darkness have seen a great light.”

Two implications for Advent

If the testimonies of our saints and martyrs like those mentioned above (who are among the faith communities’ mnemonic clues, most of whom have no feast day) are accurate, there are at least two implications for our Advent convictions.

First, to practice incarnation — the spectacle of God’s own embodiment in the human drama — is to emulate such embodiment, and to do so specifically in the sinister side of history, to be compassionately proximate with those communities considered disposable and expendable by the powers that be, and doing so despite knowing the costs could be great. The figures summarized above knew it was more likely that Herod’s agents would be coming to their towns, not Santa.

If we who are not among such communities are to know what the Spirit is doing and join ourselves to that work — if hope is to be more than cheery sentiment — it is imperative that we intentionally risk some of our privilege to be present in the company of those dwelling on the underside of bridges, the short side of markets, the wrong side of the tracks, the inside of refugee camps. The light of heaven is promised only to those who dwell in such shadows, where fear is endemic, threat is pervasive, and bodies shiver from terror.

If Pentecostal “tongues of fire” alight on us, it is not self-immolation. It is doxology. It is praise. It is a hallelujah moment of recognition that death is not the last word; that sorrow, though enduring through the night, transforms into joy in redemption’s bright morning.

Therefore, our cheerful Christmas lights are reminders of this prophecy of the “great light” to come. Indeed, like the magi, there are those outside the household of faith who also discern the meaning of that twinkling little star.

The church’s little-known Feast of the Holy Innocents — marking the painful memory of Bethlehem’s slain infants three days after the Nativity — is evidence that we live amid outbreaks of Herod’s murderous rampage.

Even in lands of relative civility, our Christmas crèche memoir has been trivialized, as when in 1984 U.S. Supreme Court Justice Warren Burger, in his opinion confirming the secular legitimacy of public courthouse Christmas displays, reasoned that it “serves the commercial interests” of merchants.

“The shadow of death and the merchandizing of joy are with us still.”

The shadow of death and the merchandizing of joy are with us still. As Bruce Cockburn sings so presciently, we are “lovers in dangerous times.”

Establish your own memory devices. These enable us to remain steadfast in our affirmation of incarnation: that God is more taken with the agony of the earth than with the ecstasy of heaven. Allow Advent’s “preparation” work to steel your resolve to engage one of the vipers that prosper on the carnage of bodies and soil alike.

Benediction — Bruce Cockburn, Lovers in Dangerous Times

Don’t the hours grow shorter as the days go by?

You never get to stop and open your eyes.

One day you’re waiting for the sky to fall,

The next you’re dazzled by the beauty of it all,

When you’re lovers in a dangerous time.

Ken Sehested is curator of prayerandpolitiks.org, an online journal at the intersection of spiritual formation and prophetic action.

Related articles:

Let’s put Herod back into Christmas | Opinion by Ken Sehested

Angel wings and devil tails: Meditation on the Feast of the Holy Innocents | Opinion by Ken Sehested