Jews have been part and parcel of the fabric of the Middle East and North Africa. Within the multireligious and multiethnic 19th-century Ottoman Empire, Jews made up more than 1% of the population. Mainly an urban community, they had a strong presence in all major centers, with the largest numbers in Baghdad, Cairo and Alexandria, followed by Aleppo, Damascus, Beirut and Jerusalem. There were two other relatively small Jewish centers in Tiberias and Safed.

Like Christianity, Judaism was a recognized millet and an integral part of the socioeconomic web of the empire, but without any political claims. It was Anglo-Saxon Christians and British politicians who encouraged the Jews in Europe to think of their religious identity as a basis for a political claim over Palestine.

Like Christianity, Judaism was a recognized millet and an integral part of the socioeconomic web of the empire, but without any political claims. It was Anglo-Saxon Christians and British politicians who encouraged the Jews in Europe to think of their religious identity as a basis for a political claim over Palestine.

Assimilation

The Anglo-Saxon world had been obsessed with Jews and Judaism since the time of the Reformation. The interpretation of Judeo-centric prophecy developed over several centuries to become an important theme in British intellectual discourse. At the heart of this interest was a desire to assimilate European Jews fully into Anglo-Saxon culture by converting them to Christianity.

Toward this goal, the London Jews Society was established in the early 19th century by politically prominent and wealthy evangelical Anglicans. In an age of sectarianism, it did not take much for this religious zeal to develop into a political program within the British colonial framework. If France had adopted a Christian denomination, the Maronites, as their protégés in Lebanon, Britain adopted European Jews as their subcontractors to colonize Palestine.

Ibrahim Pasha

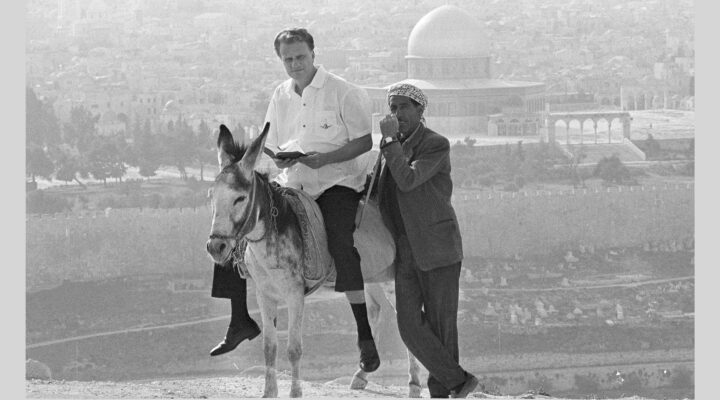

The occupation of Palestine in 1831 by Ibrahim Pasha, Muhammad Ali’s son, triggered this development. The policy of tolerance by Muhammad Ali toward Christians and Jews enabled John Nicolayson, a missionary of the London Jews Society, to settle in Jerusalem in 1833 and to buy two pieces of land in 1838 with the aim of building an Anglican church for converted Jews. This coincided with the opening of a British consulate in Jerusalem.

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, prominent figure in the evangelical Anglican movement and a member of the British House of Commons, followed these developments in Jerusalem closely. In January 1839 he published an article in the Quarterly Review calling for the settlement of Jews in Palestine.

The soil and climate of Palestine are singularly adapted to the growth of produce required for the exigencies of Great Britain; the finest cotton may be obtained in almost unlimited abundance; silk and madder are the staple of the country, and olive oil is now, as it ever was, the very fatness of the land. Capital and skill are alone required: the presence of a British officer, and the increased security of property which his presence will confer, may invite them from these islands to the cultivation of Palestine; and the Jews, who will betake themselves to agriculture in no other land, having found, in the English consul, a mediator between their people and the Pacha, will probably return in yet greater numbers, and become once more the husbandmen of Judaea and Galilee.

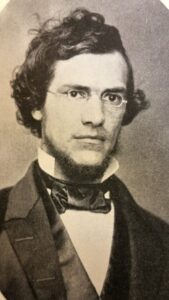

Anthony Ashley-Cooper

Lord Shaftesbury saw Palestine as a land with great agricultural potential that could serve the economic expansion of the British Empire and requiring simply the capital and skills that British Jews possessed to unlock this potential.

Accelerating political developments

Political developments in Palestine were accelerating. In 1840, Britain and Austria decided to aid the Ottomans against Ibrahim Pasha and were successful in pushing Pasha back from Syria and Palestine, leaving Egypt under his control. While Prussia wanted Palestine to be under a Christian protectorate, British diplomats were busy convincing European Jews to claim Palestine politically for themselves under British imperial rule.

Less than four months after the defeat of Ibrahim Pasha’s troops in Palestine (on June 14, 1841), Charles Henry Churchill, the British consulate in Ottoman Syria who wrote about the civil war on Mount Lebanon, wrote a letter to Sir Moses Montefiore, president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, proposing a strategy for a Jewish national claim to Palestine. This letter is very interesting as it shows that it was not the Jews themselves who thought of Palestine as a homeland but Anglo-Saxon evangelical Christians with political clout.

Charles Henry Churchill

In this letter, we read:

I cannot conceal from you my most anxious desire to see your countrymen endeavour once more to resume their existence as a people.

I consider the object to be perfectly attainable. But two things are indispensably necessary. Firstly, that the Jews will themselves take up the matter universally and unanimously. Secondly, that the European Powers will aid them in their views. It is for the Jews to make a commencement. Let the principal persons of their community place themselves at the head of the movement. Let them meet, concert and petition. In fact, the agitation must be simultaneous throughout Europe. There is no Government which can possibly take offence at such public meetings. The result would be that you would conjure up a new element in Eastern diplomacy — an element which under such auspices as those of the wealthy and influential members of the Jewish community could not fail not only of attracting great attention and of exciting extraordinary interest, but also of producing great events. Were the resources which you all possess steadily directed towards the regeneration of Syria and Palestine, there cannot be a doubt but that, under the blessing of the Most High, those countries would amply repay the undertaking, and that you would end by obtaining the sovereignty of at least Palestine. Syria and Palestine, in a word, must be taken under European protection and governed in the sense and according to the spirit of European administration. It must ultimately come to this. What a great advantage it would be, nay, how indispensably necessary, when at length the Eastern Question comes to be argued and debated with this new ray of light thrown around it, for the Jews to be ready and prepared to say: “Behold us here all waiting, burning to return to that land which you seek to remould and regenerate. Already we feel ourselves a people. The sentiment has gone forth amongst us and has been agitated and has become to us a second nature; that Palestine demands back again her sons. We only ask a summons from these Powers on whose counsels the fate of the East depends to enter upon the glorious task of rescuing our beloved country from the withering influence of centuries of desolation and of crowning her plains and valleys and mountain-tops once more, with all the beauty and freshness and abundance of her pristine greatness.”

Ottoman soldiers and statesmen in Palestine.

Churchill wrote first to Montefiore in Britain in the belief that he and other influential European Jews should work on lobbying the five great European powers. Simultaneously, he prepared a petition to be signed by Ottoman Jews in Syria out of his conviction that only Ottoman Jews could petition the Porte to “regain a footing in Palestine” in a kind of autonomy within the Ottoman Empire, yet under British protection.

Churchill was convinced that the latest developments in Palestine and the restoration of Ottoman sovereignty over Palestine offered an opportune moment to implement such a plan. He wrote: “Political events seem to warrant the conclusion that the hour is nigh at hand when the Jewish people may justly and with every reasonable prospect of success put their hands to the glorious work of National Regeneration.”

The ‘Jewish question’

It is interesting how Churchill then ends his letter. He is unsure how Sir Montefiore will interpret his intentions. To ask British and European Jews to reclaim and settle in Palestine may have been interpreted in the 19th century as wanting to resolve the “Jewish question” by relocating European Jews to Palestine. Nineteenth-century Europe was eager for the Jewish community to fully assimilate and blend within national settings, with conversion to Christianity as the best proof of assimilation.

Yet, Jews were projected as an ancient ethnoreligious tribe belonging to the Middle East that had ended up in Europe by a kind of a mistake and thus needed to be relocated. Such an idea could be interpreted as racism. Churchill was, therefore, keen to clarify his motives, especially as he was unsure whether his idea would appeal to a British Jewish banker and philanthropist like Montefiore.

“Jews were projected as an ancient ethnoreligious tribe belonging to the Middle East that had ended up in Europe by a kind of a mistake and thus needed to be relocated.”

He wrote: “If you think otherwise, I shall bend at once to your decision, only begging you to appreciate my motive, which is simply an ardent desire for the welfare and prosperity of a people to whom we all owe our possession of those blessed truths which direct our minds with unerring faith to the enjoyment of another and better world.”

Churchill is assuring Montefiore that his intentions are well intentioned and biblical. For Churchill, the plan was not driven by political calculations but by religious conviction and belief. Thus, Churchill is describing himself as an evangelical Christian Zionist.

Christian Zionism preceded Jewish Zionism by half a century. The seed that Churchill planted bore fruit. In 1860, Sir Moses Montefiore sponsored the establishment of the first Jewish colony in Palestine, just outside the Old City in Jerusalem and opposite Jaffa Gate.

Throughout history, Christian Zionists interpreted almost every major political event in the Middle East through the lens of biblical prophecy. Churchill read the defeat of Ibrahim Pasha through this lens. A decade later, the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury read the Crimean War (1853–1856) through this same lens.

The immediate cause of the war was a struggle between France and Russia over Christian rights at holy sites, specifically at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. France sided with the Catholics while Russia took the side of the Greek Orthodox monks. Britain decided to aid the Ottomans in their battle against Russia. In this context in 1854 and as an evangelical Christian, the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury was less interested in the holy sites and their control. His interest was who would obtain the rights over the Holy Land: Palestine and Syria. He wrote in his diary:

“Throughout history, Christian Zionists interpreted almost every major political event in the Middle East through the lens of biblical prophecy.”

The Turkish Empire is in rapid decay; every nation is restless; all hearts expect some great things. … No one can say that we are anticipating prophecy; the requirements of it (prophecy) seem nearly fulfilled; Syria “is wasted without an inhabitant”; these vast and fertile regions will soon be without a ruler, without a known and acknowledged power to claim domination. The territory must be assigned to someone or other; can it be given to any European potentate? To any American colony? To any Asiatic sovereign or tribe? Are these aspirants from Africa to fasten a demand on the soil from Hamath to the river of Egypt? No, no, no! There is a country without a nation; a nation without country. His own once loved, nay, still loved people, the sons of Abraham, of Isaac, and of Jacob.

To ‘claim domination’

As the European empires tussled over resources, trade routes and the very future of the Ottoman Empire, Lord Shaftesbury saw an opportunity for Britain to “claim domination” over Palestine, and he used British Jews to that end. Shaftesbury’s statement blended the biblical language of prophecy with the imperial interests of the British Empire. It was as if Britain was to be the instrument for the fulfillment of these biblical prophecies that had been waiting for generations. God’s promises and imperial interests went hand in hand.

Evangelical Christians, following Lord Shaftesbury, initially concentrated on the “restoration” to the Jewish people of what was regarded as their ancient homeland, Palestine. This policy may have had less to do with love for the Jews than with anti-Semitism; sending British Jews to Palestine not only served British imperial interests but could, in the unspoken hope of British politicians, solve the Jewish issue.

British politicians were uneasy about the political and economic influence of British Jewry inside Britain and were frightened by waves of impoverished Eastern European Jewish migrants flooding into Britain. Alongside the Aliens Act of 1905, Jews could be prevented from coming to Britain by diverting them to their “homeland” of Palestine. With shrinking space for Jews in Europe, the Zionist movement gradually adopted this particular Christian view of history and its use of biblical prophecy to escape Europe, thereby translating Zionism into a real political agenda.

“With shrinking space for Jews in Europe, the Zionist movement gradually adopted this particular Christian view of history and its use of biblical prophecy to escape Europe, thereby translating Zionism into a real political agenda.”

In Der Juden Staat published in 1896, Theodor Herzl adopted this Anglo-European plan for a Jewish nation-state as an outpost of Western civilization, where British Jews could be the managers with Eastern European Jews as the cheap labor to develop the barren land of Palestine.

New movement after World War I

The outcome of the First World War gave the movement the breakthrough it was working toward. On November 2, 1917, the first Lord Arthur James Balfour, British foreign secretary, wrote to his colleague in Parliament and prominent British Jewish banker, Baron Walter Rothschild (1868–1937):

I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty’s Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet: His Majesty’s Government view will favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this objective, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

The formal transfer of Jerusalem to British rule in 1917, with a “native priest” reading the proclamation from the steps of the Tower of David. (Wikipedia)

The timing of this English cabinet decision was not by chance. The British army, stationed in Egypt, was ready to storm southern Palestine. On Nov. 22, just a few weeks after this declaration, Jerusalem was occupied by the Commander in Chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, Sir Edmund Allenby. The four-century-long Ottoman occupation of the Middle East came to an end.

The “biblical promise” now became the imperial promise of Palestine to the European Jews. This British promise was promoted from Britain’s new imperialist agenda of “colonial development.”

Palestine was thus seen as an important piece in the emerging puzzle of Britain’s future role in the region, particularly because of its prime coastal location: “There is no doubt whatever that the agricultural productivity of the country (Palestine) can be vastly increased; and it is equally certain that with proper harbours and railways it can become as of old a great highway of communication between the Mediterranean and the East.”

Jewish capital and agricultural know-how would serve this noble imperial project. The “great highway” promised in Isaiah 40 was projected into the British interest in controlling and protecting trade routes. The “wasted land” was no longer wasted if tended by European Jews serving British interests. The land was depicted as “a land without a people” because the native inhabitants, Christians and Muslims who made up 95% of the population, were portrayed negatively as “non-Jewish communities” who might have “civil and religious rights” but no national rights since they were not a “people” in the authentic sense of the word.

Christian Zionist discourse openly “constructed friends (Jews) as well as enemies (Muslims and Roman Catholics), while cultivating an occidentocentric discourse that discounted Eastern Christians. These constructions are manifested in contemporary Western discourse surrounding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that cast Jews within eschatological dramas while demonizing Muslims and casting aspersions on Christians who are Palestinian or sympathetic to the Palestinian national cause.”

This sectarian Christian Zionist approach proved to be disastrous in Palestine. The myopic interpretation of biblical prophecy led to the establishment of a political entity in Palestine based on religious affiliation. It gave exclusive national rights to a religious minority, thus discriminating against the followers of the other two religions — Muslims and Christians. — who constituted 95% of the population of Palestine. It created in Palestine an exclusive sectarian political entity as part of an imperial colonial project implemented by the Zionist movement, with catastrophic implications for the whole region.

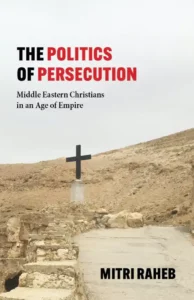

Mitri Raheb

Mitri Raheb is a Palestinian Christian and founder and president of Dar al-Kalima University in Bethlehem. The most widely published Palestinian theologian to date, he is the author of more than 40 books. This article is excerpted from his new book The Politics of Persecution: Middle Eastern Christians in an Age of Empire. Copyright © Baylor University Press, 2021. Reprinted by arrangement with Baylor University Press. All rights reserved.

Related articles:

Apartheid in Palestine and a Christ who stands on the other side of the wall | Analysis by Chris Conley

Baptist convention denounces ‘oppression and violence’ toward Palestinians

A Palestinian Christian’s cry for justice | Opinion by Rob Sellers