Demographers have been predicting for three decades that the United States was headed toward a non-majority status for any single racial group in the population. Results of the 2020 Census released last week confirm that ongoing trend, but the real picture is more complicated than that.

One of the big stories of the once-every-10-years Census is a better understanding of how many Americans consider themselves multiracial.

For example, 57.8% of the population identified only as white, a new low. But 61.5% of the population identified as white and something else at the same time.

The multiracial population was measured at 9 million people in 2010 and is at 33.8 million people in 2020, a 276% increase. While there has been legitimate growth in the multicultural population, comparing previous Census data to the new Census is not always apples to apples.

New look at multiculturalism

This new look at multiculturalism was made possible by changes made to the questions the Census Bureau asked in this this cycle. A Bureau news release explained: “The improvements and changes enabled a more thorough and accurate depiction of how people self-identify, yielding a more accurate portrait of how people report their Hispanic origin and race within the context of a two-question format. These changes reveal that the U.S. population is much more multiracial and more diverse than what we measured in the past.”

So answering the question of whether the white population in America has grown or shrunk in the past decade depends on how you ask the question. If considering only those who check white as their only descriptor, that population declined 8.6%. But if considering those who identified only as white plus those who identified as white and something else, that population increased 1.9%

So answering the question of whether the white population in America has grown or shrunk in the past decade depends on how you ask the question. If considering only those who check white as their only descriptor, that population declined 8.6%. But if considering those who identified only as white plus those who identified as white and something else, that population increased 1.9%

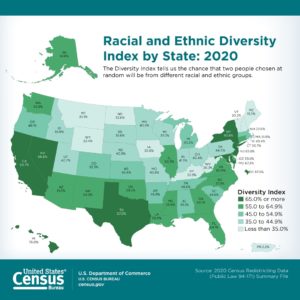

The new Census data also considers racial diversity on a state-by-state level and finds that Maine, Vermont, West Virginia, New Hampshire, Wyoming, Montana and Iowa are the most-white states in the union. Maine clocked in at 90.8% white and Iowa, one of the constant bellwethers in early presidential campaigning, clocked in 84.5% white — dramatically different than the U.S. population as a whole.

On the other end of the scale, Hawaii is the least-white state, at only 22.9%, followed by the District of Columbia (39.6%), California (41.2%), Maryland (48.7%) and Texas (50.1%).

One in five Americans threatened by ethnic changes

The new Census data gives an interesting interpretive tool for the PRRI 2020 American Values Survey, which found that 18% of Americans are “bothered” by the idea of most Americans not being white. And while the vast majority of Americans (81%) are not bothered by this emerging reality, now-familiar patterns of political affiliation make a difference.

More than one-fourth of Republicans (27%) agree that they are bothered by the idea of most Americans not being white, compared to 16% of independents and 13% of Democrats.

Columnist Charles Blow writing in the New York Times last week predicted that for some Americans, the new Census data will be “downright frightening.”

“Much of what we have seen in recent years — the rise of Donald Trump, xenophobia and racist efforts to enshrine or at least extend white power by packing the courts and suppressing minority votes — has been rooted in a fear of political, cultural and economic displacement,” he wrote. “The white power acolytes saw this train approaching from a distance — the browning of America, the shrinking of the white population and the explosion of the non-white — and they did everything they could to head it off.”

He quoted a news article from the Times that reported Hispanics accounted for about half the country’s growth over the past decade, up by about 23%, while the Asian population grew faster than expected — up by about 36%.

Not only did the white population continue to decline as a percentage of the population, for the first time in America’s history it declined in absolute numbers.

Not only did the white population continue to decline as a percentage of the population, for the first time in America’s history it declined in absolute numbers.

“This data is dreadful for white supremacists,” Blow wrote. “As Kathleen Belew, an assistant professor of U.S. history at the University of Chicago, told me by phone, ‘These people experience this kind of shift as an apocalyptic threat.’”

Growth of metro areas

In other highlights from the 2020 Census, the population of U.S. metro areas grew by 9% from 2010 to 2020, now placing 86% of the adult population living in metro areas compared to 85% in 2010. While that shift was relatively subtle in the past decade, it is more pronounced when taking a longer view. In 1960, 69.9% of the U.S. population lived in urban areas — a full 17-point change in the past 60 years.

“Many counties within metro areas saw growth, especially those in the South and West. However, as we’ve been seeing in our annual population estimates, our nation is growing slower than it used to,” said Marc Perry, a senior demographer at the Census Bureau. “This decline is evident at the local level where around 52% of the counties in the United States saw their 2020 Census populations decrease from their 2010 Census populations.”

Implications for churches

The growth of America’s multicultural population presents a unique challenge to the nation’s Christian churches, which historically have been among the most segregated institutions in society. Martin Luther King Jr. famously quipped that 11:00 on Sunday mornings was the most segregated hour of the week.

The growth of America’s multicultural population presents a unique challenge to the nation’s Christian churches.

Although progress has been made, King’s assessment remains largely true, and for a variety of reasons, including cultural preferences in worship styles.

One way researchers consider this data is by establishing a threshold of at least 20% of a congregation being racially or ethnically diverse. Or put another way, no more than 80% of a congregation is made up of one racial or ethnic group.

Using this measure, one 2020 study found that evangelical churches have experienced the most growth in multicultural congregations, from 7% in 1998 to 23% in 2019. By comparison, 24% of Catholic congregations were found to be multicultural and only 11% of mainline Protestant congregations.

Yet one glaring problem remains in these “multicultural” churches: The pastoral leadership is almost always white.

Chanequa Walker-Barnes

Chanequa Walker-Barnes, a clinical psychologist, public theologian, and minister who serves on the faculty of Mercer University’s McAfee School of Theology, explained this challenge in a 2018 column.

“A truly multicultural congregation is one in which the membership and leadership are comprised of two or more culturally distinct groups that share power and influence over the church’s governance, worship, theology and doctrine, and programming,” she wrote. “The leadership is especially intentional in ensuring that multiple cultural traditions shape its preaching, teaching and worship on a daily basis. … A truly multicultural congregation recognizes that no one cultural group has a complete understanding of God’s kingdom and that everyone benefits when they embrace and learn from different groups’ views of the divine. In a truly multicultural congregation, everyone learns to code-switch, not just the people of color.”

Other recent studies have found that ethnically diverse congregations almost always involve Black people joining white-majority congregations, and not the other way around.

“The percentage of Black congregations bringing in white worshipers is less than 1%,” Kevin Dougherty, a sociologist at Baylor University, told the Washington Post.

Related articles:

Barna: Racism a reality even in multiracial churches

Contrary to what you’ve heard, study finds churches thrive with racial diversity

More churches defined as racially diverse but that doesn’t lead to racial justice work

Study: church diversity does not guarantee diverse thinking, beliefs

Pastors say worship makes difference in multiethnic congregations