On March 18, 2022, Fred Shuttlesworth, one of the least known but most impactful figures in the Civil Rights movement, would have celebrated his 100th birthday. Unless you are a historian of that movement or one of my friends, you probably never heard of him.

Quick pop quiz: Before you began reading this article, how many of you have heard of “Bull” Connor? Of George Wallace? Of Fred Shuttlesworth? I don’t even want to know how many hands were raised.

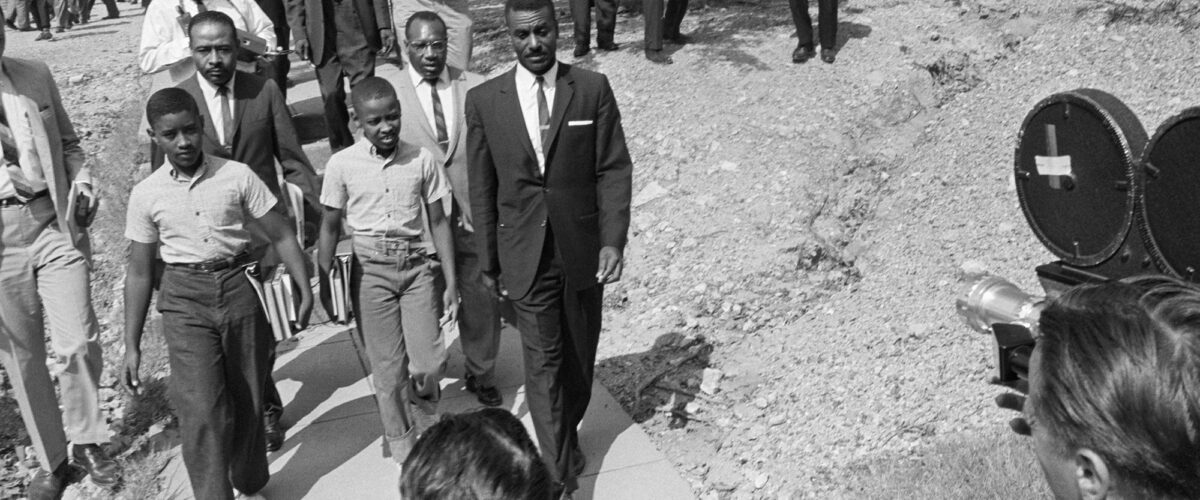

Firefighters use fire hoses to subdue protestors during the Birmingham Campaign in Birmingham, Ala., May 1963. The movement, which called for the integration of African Americans in schools, was organized by Fred Shuttlesworth. (Photo by Frank Rockstroh/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

But how many of you have seen the photographs of police dogs and fire hoses from the 1963 racial protests in Birmingham? Martin Luther King Jr. spent four weeks in Birmingham that spring, but not a drop of water from those hoses fell on him. Fred Shuttlesworth had spent 10 years in the capital city of segregation, surviving bombings (twice), beatings at the hands of Connor’s henchmen, and a blast of water from his firefighters and their hoses that could take the bark off trees.

He also spent nearly four years requesting, cajoling, even pestering King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference to come join with his organization, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights to attack segregation at its strongest point. “Come to Birmingham,” he kept insisting, “and we’ll shake up the whole country.”

And he was right. The Birmingham demonstrations finally convinced a reluctant and racially timid President John F. Kennedy to introduce what became the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Shuttlesworth re-invigorated the work of King, whose civil rights efforts for six years after the Montgomery Bus Boycott had achieved only modest success. In 2017, Clayborne Carson, director of the MLK Papers Project at Stanford University, asked an audience at BYU, what if King had failed in Birmingham, would he have been asked to give the “I Have a Dream” speech or won the Nobel Peace Prize?” No, none of those high points in King’s career would have happened without the Birmingham demonstrations, which were unimaginable without Fred Shuttlesworth.

Dynamited parsonage of Fred L. Shuttlesworth. The 1956 bombing was in retaliation for his leadership in the struggle against segregated busing. His children were injured in the Christmas night blast. (Photo by Don Cravens/Getty Images)

On Christmas Day 1956, the same bombers who killed four little girls in 1963 bombed Shuttlesworth’s home with 16 sticks of dynamite under the floor under the bed in which he lay. Yet the next day he led more than 100 followers to flout segregated seating ordinances on buses in “Bombingham.”

In early September 1957, the Klan beat up and nearly castrated a Black man, telling him, “This is what will happen to anyone who tries to integrate Birmingham’s schools.” When Shuttlesworth showed up at Phillips High School a week later, he was beaten half to death by a bloodthirsty mob. Responding to a doctor shocked that his patient didn’t even have a concussion, Shuttlesworth said, “Doc, the Lord knew I lived in a hard town, so he gave me a hard head.”

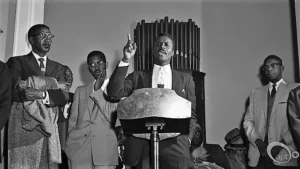

In 1958, Connor dispatched his fire department to put out a non-existent fire as a ruse to scare Shuttlesworth away from his supporters. Shuttlesworth nevertheless confronted the fire chief, saying: “Chief, you know there ain’t no fire in here. The kind of fire we have in here you can’t put out with hoses or axes.” The unextinguishable fire of protest was in the hearts of Fred Shuttlesworth, his followers and the activist wing of the African American churches.

Later, he encouraged and coached college students to sit-in at department stores in Birmingham. He was protector and father-figure to Freedom Riders beaten in Aniston, Ala., in 1961. That he did not die as a martyr to the cause of racial justice was not for lack of trying. To use his words, he “tried to get killed in Birmingham.” At times, friend and foe alike believed he had lost his mind.

“The kind of fire we have in here you can’t put out with hoses or axes.”

Bull Connor’s men hired J.B. Stoner to assassinate Shuttlesworth, leading to a second bombing and a second escape. When he was slammed by the fire hoses into the side of the 16th Street Baptist Church, Shuttlesworth was sent to the hospital in an ambulance, to which Connor retorted, “I wish they’d carried him away in a hearse.”

Yet, after all that, on the 30th anniversary of the demonstrations, NBC’s Dateline aired an episode celebrating King and his victory. The program never mentioned Shuttlesworth’s name, despite his death-defying courage and the ability to enlist the masses, which set the table for King’s most successful protest effort. This centennial of Shuttlesworth’s birth is a fitting time to set the record straight.

Fred Shuttlesworth

At Shuttlesworth’s 2011 funeral, Andrew Young’s tribute was clear: “Fred Shuttlesworth saved the Civil Rights movement.” In fact, in a recent interview, Young went so far as to say that it was Fred Shuttlesworth who should have given the “I have a dream speech,” at the 1963 March on Washington.

Always advocating nonviolence, always willing to die for the cause of racial justice, Fred Shuttlesworth — perhaps outside of the Birmingham-Shuttlesworth Airport — remains the forgotten man of the Civil Rights movement. Many movement activists who did much less than Shuttlesworth for the cause have been honored by both Democratic and Republican presidents with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. But Shuttlesworth, a pioneer in intersecting religious faith and human rights activism, obedience to a universal truth, and civil disobedience, has been left out. Even President Obama, who as a presidential candidate pushed Shuttlesworth in a wheelchair across Selma’s famous Edmund Pettus Bridge, failed properly to honor this un-venerated icon of the movement.

The man King called “one of the nation’s most courageous freedom fighters” believed the struggle for social justice was of vital importance not just for African Americans, but for human beings everywhere. He discerned the deep moral imperatives of the movement that changed the world.

On his hundredth birthday, celebrating his legacy is in order and honoring him nationally is long overdue. Happy Birthday, Rev. Shuttlesworth. Thank you for leaving America better than you found it.

Unlike the Happy Birthday song we sing in the English-speaking world, the most popular birthday song in Greece actually has some powerful content applicable to Shuttlesworth’s life:

To your life, Fred Shuttlesworth!

May you have many years.

May you grow old and have white hair.

May you everywhere spread the light of knowledge

And may everyone say, “Now there goes a wise man.”

A wise and courageous and compassionate and good man. Happy Birthday, Reverend, and rest in peace. May a grateful nation now, belatedly, take notice.

Andrew Manis

Andrew M. Manis is emeritus professor of history at Middle Georgia State University and author of A Fire You Can’t Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham’s Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth. He is currently working with Mark V. Puroshotham, producer and director of Mercy Pictures, on a documentary based on the book. Learn more about that project by emailing [email protected].

Related articles:

No one did more to kill Jim Crow than Fred Shuttlesworth | Opinion by Alan Bean

Fred Shuttlesworth and Steve Jobs | Opinion by Bill Webb