La versión en español está disponible aquí.

La versión en español está disponible aquí.

The cross is one of the most significant and powerful symbols in Christianity. Throughout history it has been perceived and used in different ways. It has been a central piece in theological reflection as well as in art. Due to the power that it holds, it has been interpreted and reinterpreted following diverse purposes, some positive while others negative.

During this past year, I had the opportunity to reflect on pieces of art that represent various uses of the cross.

In a recent trip to Mexico City, my family and I decided to visit the Chapultepec Castle, the National Museum of History. As we walked through its halls, a mural caught my attention. It was painted in 1962 by Juan O’Gorman, and it represents a narrative of Mexico’s history between 1784 and 1814, a period that involves the last part of the colony and the beginning of the independence.

In a recent trip to Mexico City, my family and I decided to visit the Chapultepec Castle, the National Museum of History. As we walked through its halls, a mural caught my attention. It was painted in 1962 by Juan O’Gorman, and it represents a narrative of Mexico’s history between 1784 and 1814, a period that involves the last part of the colony and the beginning of the independence.

As a theologian, I tend to set my eyes on the religious meanings of art pieces. This particular mural was distressing because it attested to a painful indigenous history, as well as an oppressive reinterpretation of the cross.

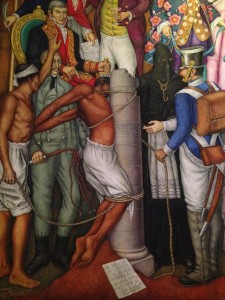

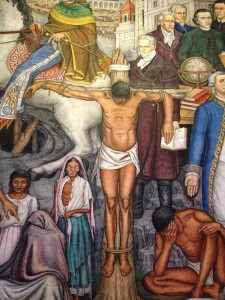

One part of the mural depicts a crucified indigenous man, and on top of the cross there are the words: “Your will be done.” The other part of the mural that caught my attention was an indigenous man, tied to a pole, and suffering violently under the hands of his executioners. At the bottom of this pole, there is a handwritten note that reads: “It seems that the Spaniards brought Christ to America to crucify the indigenous people.” In the pole’s middle section, there is a script stating: “Let it be known that the natives of this New Spain were born to be silent and obey, and not to get involved or give an opinion on the high business of government.” It is signed by the viceroy.

This is a sad story of indigenous oppression that occurred not only in Mexico, but in many Latin American countries. Some indigenous people were wiped out completely from their lands, while others survived under harsh oppressive conditions. The theology that was used to manipulate these indigenous people was centered on the suffering Christ as a model of life. The main message was: You should suffer here on earth like Jesus, then you will receive your reward in heaven, just like him. This is God’s will.

This is a sad story of indigenous oppression that occurred not only in Mexico, but in many Latin American countries. Some indigenous people were wiped out completely from their lands, while others survived under harsh oppressive conditions. The theology that was used to manipulate these indigenous people was centered on the suffering Christ as a model of life. The main message was: You should suffer here on earth like Jesus, then you will receive your reward in heaven, just like him. This is God’s will.

The saddest part is that this same sense of being crucified continues to be expressed today through the art of indigenous people in Chiapas, Mexico. As one travels throughout the state today, it is common to find pieces of art that represent crosses with crucified indigenous women or men.

This week as we reflect on Jesus’ death and resurrection, let’s also make time to evaluate our view of the cross. While the cross was a sign of shame and excruciating suffering during Jesus’ time, today it can continue to be so for many who still feel as if they were crucified through oppressive theologies.

Dr. Justo Gonzalez highlights that Protestants are people of the empty cross. He observes that crosses in Protestant churches generally are empty, in contrast to Catholic ones that tend to have a crucified Jesus on them. He warns us, however, that there is a risk with the empty crosses. It resides precisely in that they are empty. Thus, people (we) may feel tempted, consciously or unconsciously, to hang someone on them.

This individual may be someone who is different from us and our people, and whom we feel needs to be controlled, manipulated, punished, or oppressed. Or perhaps, this person is someone more familiar. It is ourselves. We may feel that we need to continue suffering due to our own past mistakes/sins, or due to challenging traits that we inherited from family.

This individual may be someone who is different from us and our people, and whom we feel needs to be controlled, manipulated, punished, or oppressed. Or perhaps, this person is someone more familiar. It is ourselves. We may feel that we need to continue suffering due to our own past mistakes/sins, or due to challenging traits that we inherited from family.

The image of the cross is powerful, and it can be used in negative ways, but also in many positive ways. Certainly the new life that Christians have found through the act of the cross is salvific.

Some months before my visit to the Chapultepec Castle, I had the opportunity to observe another piece of art based on the cross. This one came from Peruvian folk art. It represents people helping each other to carry their own crosses in an act of solidarity. The same solidarity that God and Jesus demonstrated toward us as God gave God’s own son and Jesus gave his life for our salvation.

Some months before my visit to the Chapultepec Castle, I had the opportunity to observe another piece of art based on the cross. This one came from Peruvian folk art. It represents people helping each other to carry their own crosses in an act of solidarity. The same solidarity that God and Jesus demonstrated toward us as God gave God’s own son and Jesus gave his life for our salvation.

As we considered this use of the cross, the questions of theologian Ignacio Ellacuría, patterned after Ignatius’ spiritual exercises, are particularly relevant. He invites us to consider today’s crucified people and our involvement in their situation: “What have I done to crucify them? What do I do to uncrucify them? What must I do for this people to rise again?”

This Easter week represents a great opportunity to reflect on the historic oppressive uses of the cross, as well as on the redemptive, life-giving ones. May it be a time to review our Christological practices in order to align them with the Jesus who challenged all sorts of oppressions, and did all that was in his hands to alleviate the suffering of the people of his time and of today.

As Christians, we love to sing hymns and songs that express our desire to be like Jesus. As we do that, it is pertinent to ask ourselves: Which Jesus are we singing/preaching about? Which Jesus are we following? Is he the one who seems to bring more oppression to the people, or is he the one who indeed brought true liberation for all human beings? Once we discern the answer, let’s act accordingly.