C.S. Lewis died 60 years ago this month, on Nov. 22, 1963 — the same day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Understandably, the shock and ensuing controversy surrounding Kennedy’s murder buried the news of Lewis’ passing.

Those who were alive at the time remember exactly where they were when they heard the pronouncement of Kennedy’s death. Lewis’ passing was an afterthought if it registered at all.

C.S. Lewis (Getty Images)

Nevertheless, by many measures the impact of “Jack” Lewis’ legacy on American culture has proved more lasting and robust than “Jack” Kennedy’s. Both men were icons of their day; but C.S. Lewis is still present in ways Kennedy is not.

A majority of his many books, both popular and academic, remain in print. Mere Christianity still stands as the No. 1 best seller in Christian Apologetics on Amazon. Greta Gerwig recently signed a deal with Netflix to write and direct two new film adaptations of stories from The Chronicles of Narnia series. The Narnia books alone have sold more than 120 million copies to date and have been translated into 47 languages.

For many Christians, especially evangelical Christians, no one in the intervening decades has rivaled, much less supplanted, Lewis as the foremost Christian writer of recent times.

Quoted and misquoted

Joel McDurmon rightly points out that what follows this quote in The Weight of Glory completely defies any attempt at chauvinistic, pro-patriarchal spin.

It must be said that Lewis also is one of the most oft quoted and misquoted writers of recent times. Memes, such as the examples below, epitomize this phenomenon. The first is emblazoned with a quote that is not his. The second features words that are his but have been pulled egregiously out of context.

Because of his stature, especially in certain circles, people of all stripes want Lewis on their “team.” In the process, they mold him in their own image, taming him into a peddler of positive aphorisms or twisting him into a demagogue of white Christian nationalism. Both approaches reduce Lewis as much as they misuse him.

William O’Flaherty of essentialcslewis.com has traced this quote back to a motivational speaker named Les Brown. How it became attached to Lewis is unknown.

Interestingly (and thankfully), nowadays I don’t see memes such as these as often as I used to. That may be primarily a function of shifting algorithms; but I sense it also may signal the waning of Lewis’ influence over the tides of American Christian culture, despite his still impressive sales figures.

A man of his era

An important and much-needed shift of recent years is that non-white, non-male, non-Oxford-educated voices have risen to prominence within our theological discourse. Still more of these diverse perspectives are needed, in fact. Conservatives may well complain Lewis is being “cancelled” by “woke” liberals; but the truth is that many pressing theological and political concerns of the 21st century, such as creation care and climate action, the societal damage wrought by American apartheid and the theological distortions caused by it and other manifestations of colonialism, simply were not on Lewis’ radar.

He was a man of his era, and as much as he helped to shape that era, he also was very much shaped by it. Like all ideas, Lewis’ rightly should be revisited and re-evaluated as our awareness, knowledge and experience (both personally and collectively) grows and develops.

Yet we would be silly (in the full British sense of that word) to ever conclude that Lewis, an Irishman who lived among the English, who possessed such an expansive, creative, widely and deeply read mind, and whose life spanned both world wars and the Great Depression, has nothing to offer us for the challenge of living faithfully in anxious, uncertain and unstable times.

“Lewis should be engaged, not lionized as an infallible saint nor dismissed as an Edwardian fossil.”

Lewis should be engaged, not lionized as an infallible saint nor dismissed as an Edwardian fossil. Fans of Lewis should also remember that, like the Apostle Paul and many other towering figures of Christian history, Lewis never has been universally revered.

C.S. Lewis (Getty Images)

The following is the entirety of E.E. Aubrey’s review of The Case for Christianity (the first series of radio addresses that would later be gathered into Mere Christianity), published in 1944 in the Journal of Religion:

The author of The Screwtape Letters here presents two series of radio talks: the one on the need for religion as an adequate rationale of moral experience, the other on Christian faith as an answer to men’s doubts. The book is well written but too cavalier in disposing of the skeptic’s difficulties. It will scarcely convince a really thoughtful atheist, and its virtual acceptance of a personal devil will surely startle intelligent Christians.

Always returning

It has been many years since I have read C.S. Lewis in any serious capacity. In many ways, my theology and my socio-political interests have grown beyond the scope of his apologetics. I have discovered (and needed) guides who have an experience of God and the world significantly different from my own to help me progress onward in my Christian journey. Yet I stand as one of the thousands if not millions of people who would not be on the Christian journey if not for the work and witness of C.S. Lewis.

Every so often, I cannot help but return to him, for the sheer delight of his language as well as the grounding of his thought.

The Narnia books, Till We Have Faces, The Four Loves, The Screwtape Letters, especially as presented and expounded by Ralph Wood at Baylor University, all spoke to me in ways the Bible did not (and could not) as an undergraduate who was stumbling forward toward adulthood, intellectually curious but thoroughly confused about the world and myself, and who had a less than stellar experience of church growing up.

“Lewis’ stories and essays enabled me to hear what the Scriptures have to say and opened a door for me to find my own way in.”

Lewis’ stories and essays enabled me to hear what the Scriptures have to say and opened a door for me to find my own way in. That is the core of why Lewis has endured and why he still matters.

And so, I could not let this 60th anniversary pass by too far without reflecting upon it and calling some measure of attention to it. For what it’s worth, what follows are brief expositions of two aspects of Lewis’ legacy that have had a lasting impact on me and that I believe speak directly to the challenges we face in our own age of upheaval. Sixty years on, Lewis still has many gifts to offer Christ’s church writ large.

Faith and imagination

At one time, I ranked The Voyage of the Dawn Treader as my favorite book in The Chronicles of Narnia series; but The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is the story I have come back to most often as both a teacher and a student. Aslan, Mr. Tumnus, Mr. and Mrs. Beaver — the characters are so very captivating and wonderfully conceived.

In the darkest, coldest part of each year I find myself recalling Mr. Tumnus’ lament over Narnia’s fate: “It’s always winter but never Christmas!” Yet, a part of this book that has lodged firmly in my spirit isn’t actually part of the story. It’s the dedication Lewis wrote to his goddaughter, Lucy Barfield, whose name he borrowed for his main character. In part, it reads:

My dear Lucy,

I wrote this for you but when I began it I had not realized that girls grow quicker than books. As a result, you are already too old for fairy tales, and by the time it is printed and bound you will be older still. But some day you [will] be old enough to start reading fairy tales again.

This quip epitomizes the charm of Lewis’ prose; but more than that, it names a remarkable aspect of life’s trajectory: We all outgrow fairy tales. A good many of us then discover, sooner or later, that we are ready to explore them again. I am convinced this return is as important a part of our ongoing growth and development as is the initial departure. We need the performative and transformative enchantment that fairy tales (broadly defined) offer in order to continue exercising, maintaining and expanding our own imaginations as we grapple with the human condition.

As human beings, our ability to imagine, to dream new worlds, new creatures, is a reflection of the imago Dei within us all, and that ability undergirds our capacity to articulate both what is and what can be.

Among the people of Jesus, the gospel grounds and the Holy Spirit guides; but in practical, tangible ways our (in)ability to imagine determines the range of our possibility. A deficit of imagination (and hence a dearth of whimsy and delight) is clear to see in the numb resignation that defines so much of our world, in the ruts that limit so much of our activity and accomplishment. Such a deficit is especially acute in large swaths of traditional, institutional Christianity that have become dry with apathy and riddled with fear because they cannot (prayerfully or otherwise) imagine anything different than the routines to which they are accustomed.

Thankfully, Lewis’ expansive imagination is still there to help us rekindle our own if our embers are burning low.

Deification

Sadly, this deficit of imagination stems directly from the conventional propagation of Protestant theologies that emphasize conformity to established doctrine, agreement with specific readings of the Bible and, more recently, allegiance to a particular political party — all of which requires little more than mental assent.

“Christianity as he presents it and understands it is neither a set of propositions to be affirmed nor an ideological line to be toed.”

For Lewis, intellectual engagement is absolutely necessary for coming to faith. However, Christianity as he presents it and understands it is neither a set of propositions to be affirmed nor an ideological line to be toed. Lived faith in Christ is emphatically not for show or self-congratulation (see Matthew 6). It concerns praxis rather than performance, substance more than structure. It is a way, not a stance.

That is because, for Lewis, the presence of Christ (God incarnate, Love incarnate) is fundamentally transformative but never coercive. We all innately bear the image of God within us. Taking on the likeness of God, however, is a process and one in which we must willfully participate.

Too many who value Lewis for his apologetic skill and evangelistic appeal miss the profundity of his rich, embodied, participatory theology. Make no mistake: Lewis was a Protestant through and through. The figure of Aslan clearly symbolizes his understanding of Christ’s death as substitutionary atonement. Nevertheless, the details of Lewis’ theological explorations in works like The Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce led Kallistos Ware to refer to Lewis as “an anonymous Orthodox” for his articulation and depiction of what the Eastern Church terms theosis or deification.

Theosis finds its most famous expression in the phrasing of Athanasius: “Christ became human that we might become divine.” In other words, faith in Christ is not just belief in God, in Jesus (or simply belief in certain things about God and Jesus); it is participation in God, in Jesus. It is a lived reality, the “partaking of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4); or, as Lewis himself phrases it in The Four Loves, “the Divine life operating under human conditions.” If we “walk with Christ” willfully by faith, we should become more fully like Christ even as we become more fully ourselves.

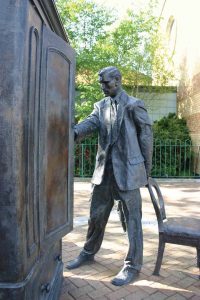

C.S. Lewis statue in Belfast, Northern Ireland. (Creative Commons)

Lewis gives vivid expression to a kind of theosis in The Great Divorce. Here we meet residents of heaven who are almost impossibly substantive, solid, real; still recognizable as themselves but utterly transformed — glorified we might rightly say. They are all, as one of them says to her ex-husband, “full now” because they are “in Love himself.”

Meanwhile, those who have caught the bus to heaven are the opposite. They are phantoms, shades. The reality of heaven, the light, even the grass, causes them discomfort. They have lost and are continuing to lose their substance. One of them, in fact, will eventually devolve into the grumbling that so defined her life on earth. It is a captivating and thought-provoking exploration of good and evil, divine and human nature, the boundlessness of God’s grace, and the stubbornness of fallen humanity’s folly that both gives a reader pause and instills them with hope.

It seems to me it is precisely this robust combination of fertile imagination and participatory theology, deep-seated hope in Christ and sober acceptance of the state of humanity and the world that enabled C.S. Lewis to navigate — and to assist so many others in navigating — personal pain as well as the violence, destruction and tumult of the 20th century.

Revisiting these dimensions of Lewis’ work certainly has helped to re-center and re-ground me in the chaos of recent days. Thus, I have no doubt that in our 21st century world, a world pervaded with deceit and distortion on a scale never before seen in human history, Lewis’ insight into the gospel can still buoy us in the storms of life and help us to resist the machinations of the powers-that-be.

That is, if we’ll revisit him from time to time, even when we feel we’ve outgrown him.

Todd Thomason is a gospel minister and justice advocate who has served as pastor of churches in Virginia, Maryland and Canada. He holds a doctor of ministry degree from Candler School of Theology at Emory University and a master of divinity degree from McAfee School of Theology at Mercer University. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate in New Testament and Christian origins at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. In addition to Baptist News Global, Todd writes at viaexmachina.com.

Related articles:

Stuck in the middle with Jesus: The future of C.S. Lewis evangelicalism | Analysis by Alan Bean

Another C.S. Lewis knock-off letter shows what evangelicals get wrong about sex | Opinion by Rick Pidcock

New initiative takes C.S. Lewis to college campuses

C.S. Lewis ‘claimed by everyone’