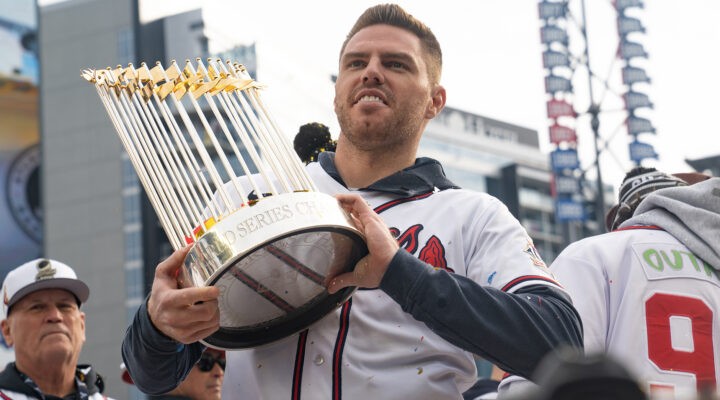

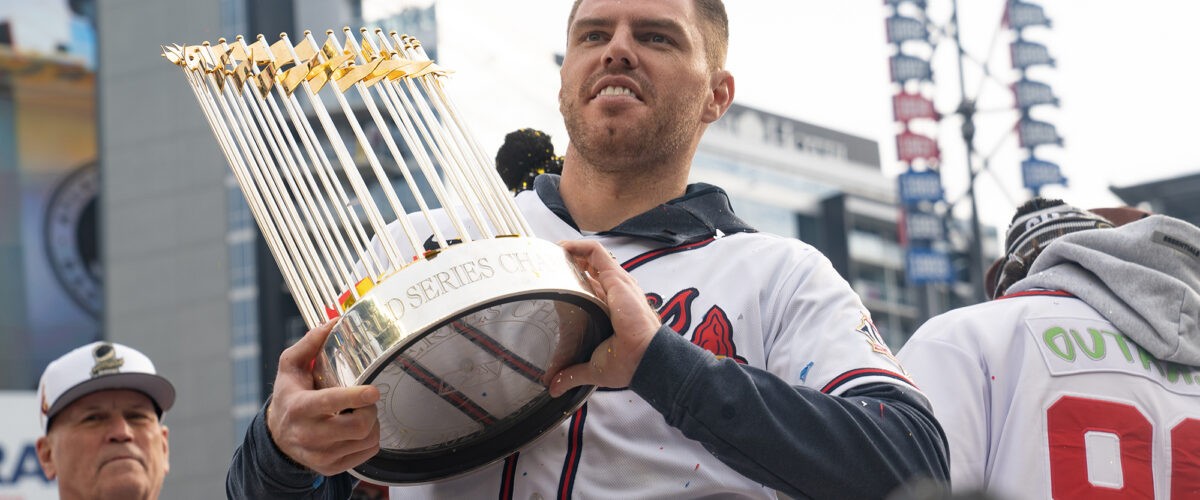

Over the last two years, Freddie Freeman, the five-time All-Star first baseman for the Atlanta Braves, has become a focus for folks eager to extrapolate the meanings of a mixture of national crises that include health, economics and the forging of cultural icons — even heroes.

At each turn there also is an opportunity to reflect upon the possibility of a soul in the ever-changing dynamics of a game that has become a lucrative business.

Here is some background that provides a picture of Freddie Freeman as a team player and a franchise loyalist. Freeman was only 17 years old when he became what professional baseball refers to as a farmhand (a way to talk about players connected to a major league franchise, beginning with the lowest level of leagues) with the Atlanta Braves organization.

Richard Wilson

From 2007 until 2021, Freeman played at every level in the Braves organization from Rookie League to A, AA, AAA and the major leagues. He also played some fall ball and winter league games.

When Freeman finally made the Atlanta Braves roster in 2010, he left his mark on the franchise and major league baseball at the national level. He became the face of the franchise, as sports reporters like to say. He was a superstar for a decade.

Along the way, Freeman appeared in five All-Star games, won the MVP (2020, which was a COVID-19 shortened season), won a gold glove for defensive skills, and, in 2021, led the Braves to their fourth championship title from their storied years in Boston and Milwaukee before coming to Atlanta in 1966.

Baseball has been a cultural compass for the United States for more than 140 years.

The game made room for regular folks. It never was a game for the cultured elite. More often than not, baseball was an outlet for the working class — both rural and urban. In the days of Jim Crow, baseball spawned the Negro Leagues that eventually recovered the political premise of “liberty and justice for all” in the United States and beyond.

When Jackie Robinson succeeded in confronting the racial barriers in professional baseball in 1947, baseball stepped into a new arena, the arena of social justice and an enduring reformation of cultural icons and heroes.

When Curt Flood balked at being traded in 1967 from the St. Louis Cardinals to the Philadelphia Phillies, he launched what became the legal emergence of free agency in professional sports. Although tied up in the courts for years, Flood’s resistance successfully challenged the notion that professional athletes were property — mere chattel — of organizations.

“From that day to this, the character and status of professional athletes has been over-shadowed by the pressures of economics and capitalism.”

From that day to this, the character and status of professional athletes has been over-shadowed by the pressures of economics and capitalism.

Time and again, cultural icons and heroes are first of all curried by the world of business (think about the millions of dollars the Atlanta Braves have made selling Freddie Freeman T-shirts, jerseys and more).

Over the last many months, baseball fans have been sucked into the drama surrounding Freeman.

I call it the Freddie Freeman Effect.

Over the last season there was a focused attention upon the dynamics of re-signing Freeman. He made it clear he wanted to be a Brave for life (like Chipper Jones). The hyped hope invigorated publicity at every level.

When the news was released last week that the Braves had traded for a superb prospect, Matt Olson — a first baseman with the Oakland Athletics for the last few years — it was clear the Braves had abandoned the face of the franchise whose loyalty to the organization has been unwavering.

That left Freeman in baseball limbo: Who would make him an offer and how might that compare to what the Braves could — should have — done?

The economic details demonstrate that Freddie Freeman did, indeed, come out on top (thanks, again, Curt Flood). Several teams in both leagues — the AL and NL — had designs on claiming a bone fide superstar in the prime of his career.

The Los Angeles Dodgers offered Freeman what the Braves would not: a six-year contract and a remarkable salary ($162 million). They welcomed him back to Southern California — he was born in Orange County. And, clearly, they gave him a more visible platform for the heart of his baseball career.

“There is no soul in corporate baseball; there is no loyalty in corporate baseball.”

In the midst of it all, however, I cannot get beyond the public anguish.

Watching the general manager of the Braves, Alex Anthopoulos, responding to reporters’ questions with his moist eyes and quivering chin tells us a lot about the process. Anthopoulos said it clearly: “It is a business.”

And then, there were interviews with Braves manager Brian Snitker and a raft of Freddie’s teammates.

Put them together and we see the business of baseball and the dynamic of playing baseball foster conflicting perspectives and emotions.

My conclusion is clear, with a nod to A League of Their Own: There is no soul in corporate baseball; there is no loyalty in corporate baseball.

Don’t miss the irony. The issues of soul and loyalty seem to escape the boardroom.

Richard Francis Wilson is professor of theology in the Columbus Roberts Department of Religion and former chair of the department in Mercer University’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. He was president of the Liberia Baptist Theological Seminary near Monrovia from 2014 to 2016.

Related articles:

Old-timey baseball players may have been the Kardashians of their day

The Atlanta Braves and the window of hope | Opinion by Richard Wilson

When following the line leads us astray | Opinion by Glen Schmucker