While the Denver Nuggets defeated the Miami Heat to win the NBA title for the first time in their 47-year history last week, Southern Baptist complementarians defeated the egalitarians to win the title of “pastor” exclusively for men for the first time in their 178-year history.

In each competition, only one team could come out on top. And the losing side never stood a chance.

But there’s more to this parallel between the NBA and the SBC than simply who ascended to the top last week. It’s a story about celebrity culture, how we handle our own success, what it means to be a team, and what kind of journalism we read and support.

Our culture’s obsession with celebrity

One of the most familiar patterns in sports media over the last century is marketing events with celebrity showdowns. When the NFL begins each fall, advertisements fill our screens featuring images of one star quarterback facing off against another.

In this year’s NBA Finals, it was the Denver Nuggets with two-time MVP Nikola Jokic and his wingman Jamal Murray going against Jimmy Butler and his sidekick Bam Adebayo.

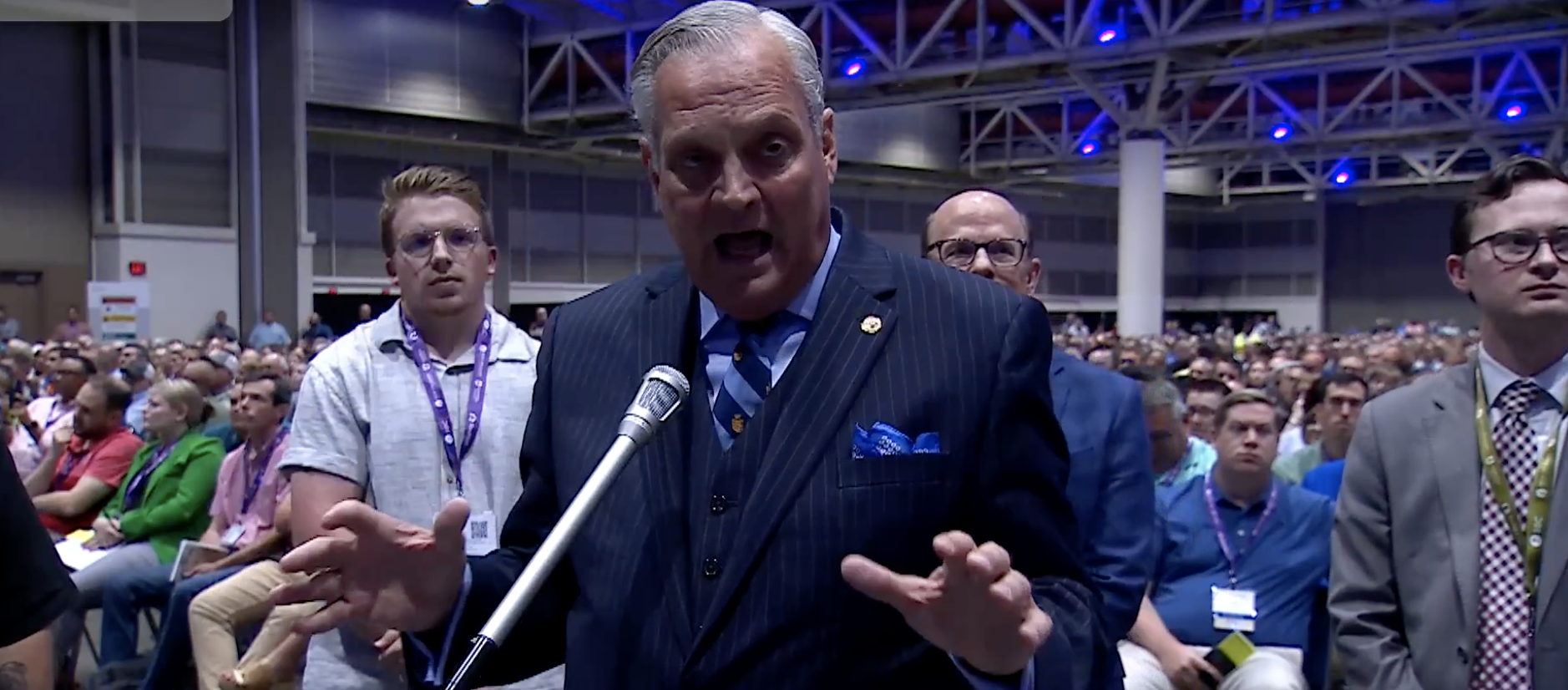

Al Mohler speaking against churches that ordain women and allow women to preach.

For the SBC, it was Al Mohler going head-to-head with Rick Warren and his fellow defendant Linda Barnes Popham.

Our culture’s obsession with celebrities can be traced at least as far back as the 18th century. Columbia University professor Sharon Marcus writes about how Jean-Jacques Rousseau published an autobiography in 1782 and then “complained that everyone was gossiping about him.” During the 18th century, she says, performers and authors began being approached by stalkers, groupies and people asking for autographs.

Marcus explains: “As literacy expanded dramatically among all classes in North America and Europe, so too did the number of those able to read about celebrities. As leisure time increased, people had more time to visit the theaters, opera houses and lecture halls where they saw celebrities in person. Even more fundamentally, democratic movements in England, France and the United States gave rise to a new emphasis on individuality.”

Individual vs. team

The tension between individualism and team is felt throughout the sports and religious worlds.

NBA games today often turn into one-on-one isolation matchups where one superstar dribbles around by himself and then shoots the ball as the shot clock runs out, while the rest of the team stands around the court and watches. It’s often referred to as “hero ball.” In the same way, churches can turn into single-person pastor performances, while the congregation looks on.

The benefit to these individualistic strategies is that the team or church can put on a great show and have astronomical success if they hire the right celebrity. Entire marketing campaigns can be built around these celebrities, which can lead to money streaming in.

But the Denver Nuggets decided to take a different approach. Rather than attempting to bring in flashy free agents, they built the team patiently over time.

Nikola Jokic was asleep in Serbia when he was drafted during a Taco Bell commercial with the 41st pick overall in 2014. He went on to become the two-time MVP as well as the Finals MVP. Despite his success, he never sought the spotlight. When asked after winning the title if he was looking forward to the parade, he answered, “No. I need to go home.” That night, he turned the trophies into drums with his daughter. Then later, his Finals MVP trophy went missing after he left it in the equipment manager’s room.

“For Jokic, all that matters is family and team.”

For Jokic, all that matters is family and team. As NBA fans learned during this year’s playoffs, Jokic is a unique center who plays like a point guard, distributing the ball to his teammates with the most precise and unexpected passes and knocking down three-point shots with ease.

The reason the Nuggets were able to win the series against the Heat in just five games was that Jokic led by example in sacrificing personal scoring statistics in order to spread the ball around and allow the entire team to get involved.

The rise and fall of evangelical ‘celebrity culture’

Even though many conservative evangelical ministries claim to be led by a team of elders, the reality is that the elder teams tend to submit to the vision of the individual preaching pastor, who often is honored as a celebrity.

Josh Butler

Before he was writing about the gospel through the lens of male-centered sexuality, Josh Butler wrote for The Gospel Coalition that one of the causes of deconstruction is “street cred.”

“Celebrities are leading the charge,” he claimed. “There’s influence to be had, platforms to be built, and money to be made.” Butler mourned the “wave of #exvangelical podcasters and TikTok stars” and the “whole cottage industry” who cheer them on.

It never seemed to cross Butler’s mind that conservative evangelical complementarian men are the ones who are leading the charge to sacralize their influence and build their platforms in the top floor of their tower of Babel, cheered on by everyone they keep locked down on the floors below them.

When Christianity Today told the story of megachurch pastor Mark Driscoll in their podcast “The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill,” they were willing to name many of the ways Driscoll abused his team of elders and his people below them more than The Gospel Coalition seems to be willing to do.

Mike Cosper

In the end, producer Mike Cosper concluded the problem was with “celebrity culture,” which he defined as a “syncretism around cultural power and influence … the phenomenon of celebrity.”

But notice the language being utilized here — words like “rise,” “fall,” “platforms” and “power.” These words are signifiers of a reality structured as hierarchy.

Celebrity culture as the worship continuum of hierarchy

In “The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill,” Cosper paired Mark Driscoll with the former celebrity pastor Josh Harris. “As I’ve thought about Josh’s story, there are two things that come to mind for me,” Cosper explained. “The first is the degree to which it’s shaped by his status as a celebrity, or in more modern terms, an influencer… . To what degree are Instagram posts from influencers a window into the divine for a secular age, ways of worshiping a little pantheon of gods that represent sex or money or beauty or power or spiritual enlightenment, including the enlightenment of having deconstructed?”

I ultimately disagreed at the time with Cosper’s decision to focus on the fruit of celebrity while deflecting questions about the hierarchical theology that produced such fruit. I also completely disagree with his characterization of those who are deconstructing. But I appreciate Cosper’s recognition of how celebrity culture is about worship.

While Hebrew words for worship have a variety of nuances, notice the hierarchical direction they tend to have:

- Yare — “to venerate, to fear with a sense of awe and respect.”

- Abad — “loyal service, obedience to commands.”

- Sharat — “to attend.”

- Shaha — “To bow down, prostrate oneself, to do homage.”

- Segid — “To do homage, prostrate oneself in worship.”

In his book Enter His Courts with Praise, Andrew Hill says worship is “submission to the will of the deity and compliance with his divine directives.” He says it literally means “falling down and groveling or even wallowing on the ground before royalty or deity.” And he also says worship carries the idea of “a vassal’s submission and loyalty to the authority of the overlord.”

“They see themselves as the overlord representatives of the divine being above them to whom we must submit.”

In other words, worship in this construct is the continuum of hierarchy, the submission and honor those below bestow on the powerful ones they honor at the top.

In the world of sports, we honor such heroes by giving of our time and money to cheer them on and build their wealth. In the world of religion, we honor them in the same way.

But with religion, men like Al Mohler, John Piper, John MacArthur, Voddie Baucham and Bill Gothard demand we submit ourselves to their directives because they see themselves as the overlord representatives of the divine being above them to whom we must submit.

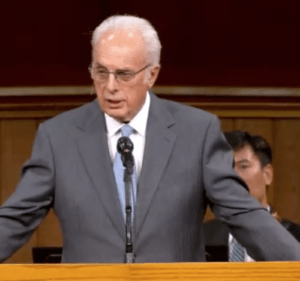

John MacArthur preaches at Grace Community Church on Sunday, Aug. 16, in defiance of a court order on public health.

John MacArthur puts it this way: “Authority and submission pervade the whole universe. In the relationship between man and man, there is authority and submission. In the relationship between man and God, there is authority and submission. In the relationship between God and God, there is authority and submission. The entire universe is pervaded by this concept. And what is new here is not that the wife is to be subject to her husband. That isn’t new, because the Old Testament taught that. What is new is the vastness, the scope of this principle. That it absolutely pervades everything.”

The role of the media in celebrity culture

Fundamental to the growth of celebrity culture is the role of the media. Marcus explained that over the past two centuries “celebrity culture would not have taken off without newspapers, but far from imposing curiosity about famous individuals on the public, newspapers used an already existing fascination with celebrities to attract more readers.”

Writers tap into the interests of readers in order to magnify what stories people find interesting.

Sportswriters came under fire leading up to the Denver Nuggets’ appearance in the NBA Finals for their lack of interest in sharing the Nuggets’ story. Chris Mannix of Sports Illustrated told Rich Eisen: “The Nuggets aren’t very interesting. Nicola Jokic is arguably the best player in the game right now. But he’s not someone who does a lot of interviews. … You remember when he won the MVP award, both times, the Nuggets had to fly over to Serbia to give it to him. He was out. He was gone. He was just hanging with his family back home in Europe.”

Contrasting the Nuggets with other NBA teams, Mannix added: “You’ve got drama in Los Angeles almost weekly. You’ve got the Suns. Can they succeed in this first year with Kevin Durant? The Warriors — all their disfunction this year. The Clippers. Can they get it together?”

He concluded: “So they’re just not a compelling team to talk about, to write about, at least not as compelling as some of the other teams I mentioned.”

In other words, sportswriters find the dysfunction of individualistic celebrities to be far more compelling than the success of a team approach that couldn’t care less about stardom.

So what does this have to do with religion?

In the same way that so many NBA teams have fascinating stories of dysfunction, over the past couple years in particular, we’ve seen the dysfunction of rightwing Christian pastor celebrities and their ministries. Whether we’re talking about Mark Driscoll, John MacArthur, C.J. Mahaney, Bill Gothard or Hillsong, the stories of abuse and coverups could be written endlessly.

Religion journalists have a responsibility to expose these men, not because it makes for entertaining articles, but due to the unspeakable harm these men cause in their sacralization of male power and obsession with violent glory.

“Like Nikola Jokic, there are many women who simply want to be home with their church family, doing the quiet work … without all of the accolades and attention.”

But like Nikola Jokic, there are many women who simply want to be home with their church family, doing the quiet work of pastoring their people without all of the accolades and attention that the media puts on them. And often, the only time we hear their names or see their faces is when male celebrity pastors target them publicly.

What kind of stories should we support?

The reason documentaries and books about abuse in the church are receiving such high ratings is not that the media is out to get Christianity, but that millions of Americans recognize these stories of abuse closely mirror their own stories or the stories of their formerly evangelical friends.

And while the mainstream media may know how to produce a good story, they tend not to recognize the nuances of hierarchy that religion journalists, scholars and pastors are aware of.

This is why Baptist News Global is such a vital resource for our world today. BNG may not have the number of readers CNN has. But its writers have a depth of knowledge about how the complexities of Christian supremacy shape our world that analysts with no religious background do not.

Marcus reflected on a similar time in journalism from the 19th century.

Newspapers in the coffeehouse etching.

“Until the 1830s, newspapers in England, France and the United States were costly publications, sponsored by wealthy patrons and read by a small, select group of subscribers who received their papers by mail. In the 1830s, the news became more commercial. To increase circulation, publishers began to charge readers only a penny instead of the traditional six cents, and began to rely on advertisements, subscriptions and daily sales, including street sales, to turn a profit. Instead of targeting a select group of insiders willing to pay handsomely for exclusive, specialized information, the new penny press appealed to general interests in an effort to reach the largest number of readers possible.”

While many news outlets are trending toward publishing their content behind subscription paywalls, BNG shares its stories in full for free with the support of those who recognize the need for religion journalism today.

BNG understands that, unlike sports, the universe is not a clashing of teams. We’re not the Christians vs. the Muslims, the straights vs. the gays, the Democrats vs. the Republicans, the Americans vs. the Iraqis, or even Al Mohler vs. Rick Warren.

Rather, the whole universe is one team, one family, one home. And in order for reconciliation to happen, we’re going to have to name, confront, repent and heal from the entitlement and violence toward others until the only title that matters is that everyone belongs and is known and loved.

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a Master of Arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.