In a June 30, 2021, essay in The Atlantic, “The Senator Who Decided to Tell the Truth,” reporter Tim Alberta describes the work of Ed McBroom, a Michigan state senator who “spent eight months searching for evidence of election fraud, but all he found was lies.”

McBroom, a conservative Republican, dairy farmer and choir director at First Baptist Church of Norway, Mich., also chairs the state Senate Oversight Committee, which spent eight intense months investigating charges of fraud in the 2020 election.

Bill Leonard

After extensive interviews, and reviews of election documents and procedures, the committee concluded: “There is no evidence presented at this time to prove either significant acts of fraud or that an organized, wide-scale effort to commit fraudulent activity was perpetrated in order to subvert the will of Michigan voters.” They added: “The Committee strongly recommends citizens use a critical eye and ear toward those who have pushed demonstrably false theories for their own personal gain.”

Donald Trump, a former U.S. president, immediately responded by calling the report a “cover-up” that prevented a “forensic audit” of the presidential election and promptly published office phone numbers for McBroom and the Republican Senate majority leader, urging citizens to “call those two senators now and get them to do the right thing, or vote them the hell out of office!”

Amid multiple threats at home and office, both online and by telephone, especially the “middle-of-the-night phone calls,” McBroom offered his own assessment of the country’s religio-political dilemma: “It’s easy to look at the current status of American culture, American politics, the American church, and be really apoplectic right now. It’s very easy to give in to that sense of panic. … But we go through different cycles in this country. I’m hoping we’re in a cycle of riots and demonstrations on and off, (and not) the cycle where we end up in civil war.”

He added: “I’ve encountered some folks who are like, ‘Maybe it’s time to rise up’ — you know, ‘refreshing the tree of liberty with the blood of patriots,’ that stuff. And I say to them, ‘Are you seriously going to go looking for people with Biden signs in their yards? I mean, is that what you’re going to do? Make a list? Is this what this is coming to? You’re ready to go out and fight your neighbors? Because I don’t think you really are. I think you’re talking stupid.’”

Alberta comments: “McBroom closed his eyes and took a heavy breath. ‘These are good people, and they’re being lied to, and they’re believing the lies … . And it’s really dangerous.’”

“Faith communities should beware lest such danger overpower them before they realize it.”

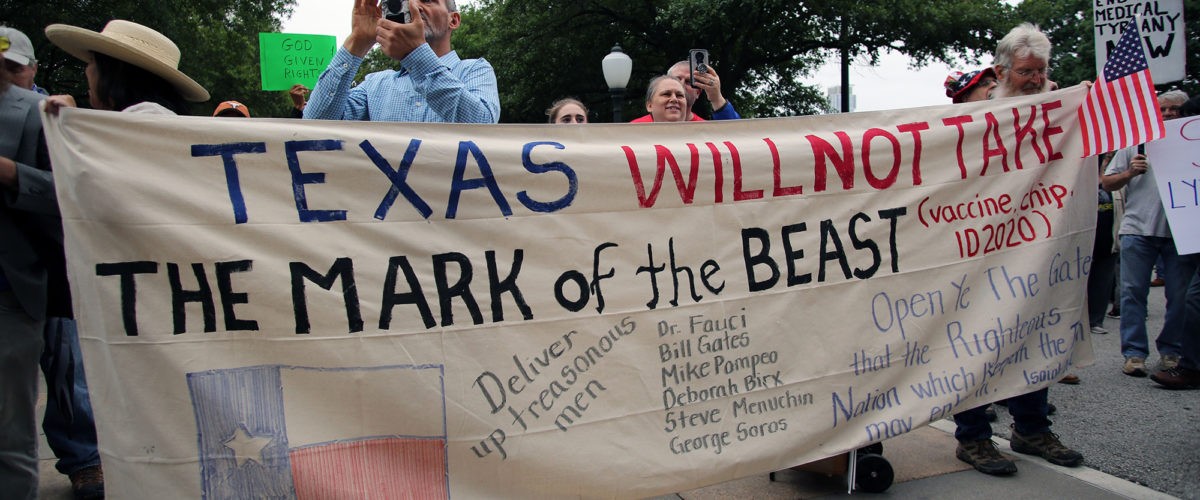

Yes, it is, and faith communities should beware lest such danger overpower them before they realize it. McBroom’s insightful inclusion of “the American church” in his comments is quite appropriate, given multiple surveys suggesting that the Jesus story is becoming dangerously intertwined with certain religio-political conspiracy theories. Consider this:

- A surprising number of pastors report divisions in their congregations over QAnon and other conspiracy theories. A June 2021 essay in Sojourners, “When Conspiracy Theories Come to Church,” cites the pastor of another Michigan Baptist church who reported that some of his members utilize both “the church and … social media” to spread specious charges that, as a presidential candidate, Joe Biden maintained “an island with an underground submarine where he receives his pedophile orders” and that there were “underground (pedophile) railroads between various cities run by Hollywood elites.” Certain congregants also claimed that as president, Donald Trump was going to “seize power, execute the liberals, and expose pedophile rings.” (Note the language of violence here.)

- A May 27, 2021, poll by Public Religion Research Institute found that Hispanic Protestants (26%), white evangelical Protestants (25%), and other Protestants of color (24%) are more likely than other religious groups to agree that the government, media, and financial worlds in the U.S. are controlled by a group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles who run a global child sex trafficking operation.” PRRI President Robert Jones calculates that percentage at some 30 million individuals. He commented: “Thinking about QAnon, if it were a religion, it would be as big as all white evangelical Protestants, or all white mainline Protestants. So it lines up there with a major religious group.”

- The PRRI survey indicates that “approximately one in four or more Hispanic Protestants (29%), Hispanic Catholics (27%), white evangelical Protestants (26%), Black Protestants (25%), other Protestants of color (24%), and other Christians (24%) agree that there is a storm coming that will sweep away the (cultural) elites in power.”

- Some 24% of white evangelical Protestants and Mormons, along with 18% of mainline Protestants, reflect the highest percentages of belief that “because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.” If the many Christian signs and symbols displayed at the Jan. 6 insurrection are any indication, some “patriot-believers” already have found a violent venue.

Questions abound: Are these American Christians co-opting conspiracy theories, or are conspiracy theories co-opting them? Are we approaching a time when segments of “the American church” seem unable to separate the Jesus story from such disreputable speculations? Or are we already there? Has the Jesus story become a useful resource for those “who have pushed demonstrably false theories for their own personal gain?” Will those Christians who refuse to believe they are “being lied to” join those who “resort to violence” to achieve their goals?

“What is to keep some Americans from believing that Christianity itself is an ancient conspiracy theory?”

And, as links between Christians and conspiracies deepen, what is to keep some Americans from believing that Christianity itself is an ancient conspiracy theory, an apocalyptic movement encouraging the use of arms to impose their fanatical theories of the “end times?”

Reflecting on all this, I went back to John Dominic Crossan’s book God and Empire, a rather brief work that has formed much of my recent thinking about gospel, history and Christianity in America in transforming ways. Crossan addresses one of Jesus’ few references to the “two kingdoms” with an insight that I think informs the current struggle between the Jesus story and conspiracy theories.

He writes: “In a magnificently parabolic scene in John’s Gospel, Pilate confronts Jesus (or does Jesus confront Pilate?) about the kingdom he proclaims. ‘My kingdom,’ says Jesus in the King James Version of the incident, ‘is not of this world: if my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight, that I should not be delivered by the Jews: but now is my kingdom not from hence.’”

Exegeting that passage, Crossan comments: “Had Jesus stopped after saying that ‘my kingdom is not of this world,’ as we so often do in quoting him, that ‘of’’ would be utterly ambiguous. ‘Not of this world’ could mean: never on earth, but always in heaven; or not now in present time, but off in the imminent or distant future; or not a matter of the exterior world, but of the interior life alone. Jesus spoils all of these possible misinterpretations by continuing with this: ‘if my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight, that I should not be delivered’ up to execution. Your soldiers hold me, Pilate, but my companions will not attack you even to save me from death. Your Roman Empire, Pilate, is based on the injustice of violence, but my divine kingdom is based on the justice of nonviolence.’”

There it is. This “justice of nonviolence” is more radical than all the phony conspiracy theories dangerously circulating in our midst. It is justice grounded in the peace of Christ, not a cringing acquiescence, but the painful, conscience-ridden, redemptive reality of grace. In 2021 and beyond, we so-called followers of the Jesus Way better get our stories straight.

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

New surveys connect the dots between politics, race, religion and vaccination

New PRRI study builds a profile of QAnon believers

Is QAnon a prophet or provocateur? And how should Christians respond? | Analysis by Aaron Coyle-Carr

Why are Christians so susceptible to conspiracy? | Analysis by Andrew Gardner