In December 1992, I graduated from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky. It was the last full year of Roy Honeycutt’s storied career as president of Southern Baptists’ first seminary.

It has been 30 years since the transition to what the seminary’s website now describes as a time of “renewal” led by Honeycutt’s successor to “remake the faculty until the seminary was entirely transformed to support the full inspiration and inerrancy of the Scriptures and evangelical, Baptist orthodoxy.”

Three decades later, I find myself nostalgic, informed, curious and still grieving the harrowing I witnessed firsthand.

Born in seminary

I was born while my father was a student at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas. In second grade, when all the other students said they wanted to become firefighters and police officers, I said I wanted to live on a ranch in Texas and teach theology at Southwestern Seminary.

Brad Bull

Mrs. Bouler smiled and said, “I hope your dreams come true.”

I wanted to follow my father’s seminary footsteps. Thus, it was a deviation when I opted to enroll at Southern Seminary and not Southwestern. I did so, in part, because an admired older friend had transferred from Southwestern to Southern and explained: “Southwestern seemed geared to getting students fired up for Jesus. I’m already fired up for Jesus; I wanted a challenging academic experience, and I found it at Southern.”

She wasn’t kidding. My Ph.D. in child and family studies at the University of Tennessee was challenging but still a cakewalk compared to the intensity of my master of divinity studies at Southern Seminary. Honestly, out of family loyalty, I would have gone to Southwestern anyway, but when some friends and I went to visit Southwestern as prospective students, one of our group had such an unwelcoming social experience on the large campus, we all decided on Southern.

Thus, I found myself at Southern Seminary and not Southwestern, as the schism in the Southern Baptist Convention was coming to a head. Here are reflections on some superlatives of that experience.

Most intense and revelatory conversation with a trustee

Things were tense on campus. In the late 1970s, Paul Pressler and Paige Patterson concocted a plan to install conservative trustees at the various Southern Baptist institutions. It took more than a decade, but it worked.

Paul Pressler (left) and Paige Patterson, architects of the SBC takeover, sit at Cafe duMonde in New Orleans June 9, 1990, comemmorating their meeting at the same spot 20 years earlier to conceive the plan to gain control of the nation’s largest non-Catholic denomination. (Photo by Thom Scott)

By the time I arrived at Southern Seminary in 1989, conservatives had a foothold among the trustees but not a strong enough majority to do all they hoped. Southern Seminary was considered one of the most offensive of the SBC seminaries to conservatives.

A faculty member once said to me, “This (controversy) is nothing compared to when we had Martin Luther King Jr. speak in chapel.” That observation was correct only in terms of the difference between an acute controversy and a chronic one. A seminary founded by slave owners had evolved into one that invited MLK to address students of a new era. Traditionalists went nuts. Thirty years later, they gained a majority of trustees on the board.

I observed that each trustee meeting brought palpable tension to campus. One trustee, still in his 20s and a student at another non-SBC seminary, had written a long article titled “The Coverup at Southern Seminary,” attacking alleged liberalism at our school. One comment asserted people would have to be “blind as a mole” not to see that Honeycutt “just doesn’t believe the Bible.” Honeycutt and the faculty were deeply loved by students, and this kind of attack fostered fear of and animosity toward the trustees.

(That trustee, incidentally, later became a faculty member at Southern Seminary under its new conservative administration.)

In this context, the administration put on a relationship-building picnic on the seminary’s quad. Large signs indicated the location of the trustees from each state. After talking to the trustee from my home state of Tennessee, I saw a large crowd across the way. I ventured to the circle and saw in the middle a young trustee whom I would learn was a layperson focusing his inquisition on theology professor Molly Marshall, the first female to earn a Ph.D. in theology from Southern Seminary. A professor later told me, “I wish students would not have given him the attention he revels in.” Thus, I am not using his actual name.

Molly Marshall outside Norton Hall at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (Photo courtesy of Good Faith Media)

After listening to my peers peppering questions and his replies, I spoke up.

“Mr. Doe, if you believe a person is going to hell if they do not know the historical Jesus of Nazareth, at what point in world history did that become the case?”

He asked, “What do you mean?”

I said, “Well, we know there were Native Americans here when Jesus was born and lived. At what point were they doomed to hell for the sin of being born in the wrong place at the wrong time? I mean, was it at the moment Jesus was born? At the moment of his baptism? At the moment of the Resurrection, the commissioning of his disciples, the Ascension? At what moment in history was everyone outside the earshot of Jerusalem doomed to hell?”

He cocked his head to the side and said: “I don’t know. I’ve never thought about it. But I can tell you had Molly Marshall for theology.” (Even asking a question was an indication of what he considered heretical theology.)

“No, sir. I’m a first-year student; I haven’t had theology yet,” I said.

Then, alluding to the final chapter of The Chronicles of Narnia and Aslan welcoming a Calmorene into heaven, I said, “But I did read C.S. Lewis when I was in college. Are you next going to propose that we remove his books from the library?”

Mr. Doe grinned and said maybe the content of the library did need to be examined.

I said, “Well, in the meantime, I’d like to suggest: Before you go firing faculty members who have spent their careers wrestling with difficult theological issues, could you at least bother yourself to think about the issues?”

Most amazing sidewalk conversation

Dale Moody was forced into early retirement from Southern Seminary in 1983 due to his controversial position on the theological issue of apostasy — the notion that people can lose their salvation. Southern Baptists typically hold to the doctrine dubbed “once saved always saved,” but Moody disagreed.

Dale Moody

Despite his lightning-rod reputation, Moody was welcomed back on campus as a chapel speaker. I remember the laughter when he said that toward the end of sermons his childhood pastor would say, “Let me recapitulate.” Moody said he was much older before he realized recapitulate did not mean “lean back and yell real loud.”

Soon after his chapel address, I was walking across campus with a friend, and we encountered Moody. We greeted him and then were treated to a priceless conversation, magnified in value when he suddenly died a few weeks later. Moody told us when he interviewed for his position at Southern Seminary in the late 1940s, he told President Ellis Fuller he could not sign the seminary’s “Abstract of Principles.” That document outlines a set of values and beliefs faculty may not contradict.

As I recall it, Moody said something like this: “I told the president I did not believe what the Abstract said about perseverance” (meaning once saved always saved). The president asked me what I believed.” Referring to the seminary’s renowned New Testament and Greek professor, Moody went on. “I said, ‘I believe what A.T. Robertson taught me.’ And Dr. Ellis said, “Anyone who follows A.T. Robertson can teach at this school, now sign the Abstract.’ So, I did. Like everyone who teaches here does.”

Waving the back of his hand dismissively toward Norton Hall, the faculty office building, Moody said, “Nobody in that building believes that stuff.” To be sure, the Abstract of Principles did not dictate what people had to believe, only that they would teach “in accordance with and not contrary to” its affirmations. How to promote education in such confines is an ongoing debate.

Best chapel experience

This one is hard. There were so many soul-enriching experiences. There was the time James Forbes said to this effect: “I knelt by my bed and pounded it with my fists until I was exhausted. Then I said, ‘OK, God; I’m ready to pray.’ Then the Holy Spirit said to me, ‘No, James; you have already prayed. Heaven is equipped to receive choreographed prayer.’” I have carried with me the message that prayer does not require words when the pain is too deep for words.

Fred Craddock

I heard Fred Craddock in multiple services. I savor his recurring exhortation, “You just don’t know,” reminding us the impact of our efforts sometimes are not apparent for years, if ever.

Then there was the hushed silence at the abrupt ending of another sermon. Craddock had described how as a Ph.D. student at Vanderbilt in the early 1960s, he had not stood up for a Black man who was being disrespected in a restaurant. He concluded, “I walked out of the restaurant in the opposite direction. And off in the distance, a cock crowed.” He bowed his head. After three beats, he closed his notebook and walked from the pulpit. I’ve never experienced such shocked stillness in a packed auditorium.

As impactful as those and other sermons were, the one I have rewatched most often on video was a sermon on urban ministry delivered by Tony Campolo. No sermon did more to influence my way of thinking, my approach to life or my own style of preaching.

Campolo told his oft-repeated story about being in a Honolulu donut shop and throwing a birthday party for a prostitute whom he had overheard the night before say she’d never had a birthday party. The next summer, I was working at a church where a seedy pool hall opened across the street. I started hanging out there, shooting pool (but refusing to bet) with hustlers, drug users and ex-cons. One of the guys got tears in his eyes when I gave him a wedding present. Years later, the church’s pastor was introducing me and said: “Brad was my intern, but he taught me so much. While I was trying to get a pool hall closed down, he saw it as an opportunity and started ministering to the people at our doorstep who I was trying to drive away.”

In addition to the power of Campolo’s message, the video version I obtained from the seminary had a tantalizing bonus. Just before the video began, there was a test pattern with audio. Campolo, apparently unaware his mic was hot, said to the person beside him on the stage, “It started when they didn’t stand up for Dale.”

Most concise letter to the editor

Remember Dale Moody getting in hot water for questioning “once saved always saved”? The opposite end of that theological doctrine is universalism, the belief that everyone will go to heaven. Remember the Southern Seminary conservative trustees who had Molly Marshall in his sites to fire?

I was working as a staff writer at the Western Recorder, the weekly news journal of Kentucky Baptists. We got a letter to the editor that concisely, incisively and rhetorically asked, “How can Dr. Molly Marshall be guilty of teaching both apostacy and universalism?”

Most effective icy stares from a seminary president

When that trustee in his 20s had written that Honeycutt didn’t believe the Bible, I was in the packed assembly when Honeycutt responded. With tears in his piercing eyes, and a slight quiver in his voice, but with the imposing figure of a lion, he described his mother giving him a pocket Bible to carry during his time in foxholes during World War II. He said the Bible was guiding and sustaining him decades before the accusing author was born. He got a standing ovation from everyone in the room — including all the trustees except the sulking author who looked like a whipped but recalcitrant schoolboy. Most students at Southern Seminary adored “Dr. Roy” and his dear wife, June.

Roy Honeycutt

However, at the end of the 1992 spring semester, a controversy arose that put many students at odds with the president. Local news reported that Louisville’s elite Pendennis Club did not allow Black members. We learned Honeycutt was a member. I was on the M.Div. Council. One of our members had written a letter accosting Honeycutt with accusations rather than questions and demanded his resignation from the club. In our discussion at our last meeting of the year, we decided to write a joint letter.

Our faculty sponsor told us: “One of the main jobs of a president is fundraising. His membership in that club provides too much exposure to wealthy donors. There’s no way he will resign from it.”

Nonetheless, during the last week of the spring semester, we composed and sent a letter stating that we had stood outside board meetings supporting him and that another form of support is constructively confronting concerns. We mentioned that Scripture says to avoid the very appearance of evil.

On the first day of the fall semester, we had a meeting with Honeycutt. He explained it was not true that the Pendennis Club did not allow Black members. He said they just happened not to have any. They had even offered a free membership to a Black activist, but that membership had been declined. I remember glancing around at my peers as our faces filled with wide-eyed guilt — except for our rogue member who was inexplicitly grinning. Then Honeycutt continued. “That said, I appreciated your letter. Your point to avoid the appearance of evil is well taken. I decided it was best to start this year with all that behind us, so I resigned from the club.”

We were stunned as we mumbled our thanks. Except Mr. Rogue who, still sporting his grin said, “Dr. Honeycutt, I sent you a letter but didn’t get a reply. Did you get my letter?” Honeycutt locked eyes with him, said, “Yes, I got it” and then just stared. His silence spoke volumes. I now was grinning inside as this veteran of war peacefully eviscerated a gadfly.

As I recall, our council chair broke the silence by thanking Honeycutt, and we rose to leave, equipped with the experience that things are not always as they appear, and much can be said by saying nothing.

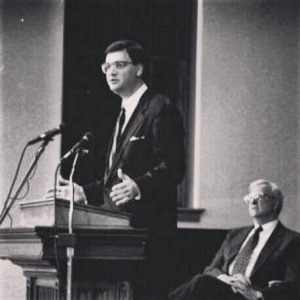

Best one-liner, bar none

Al Mohler, the day of his election as seminary president in 1993, with Roy Honeycutt behind him.

Honeycutt’s 33-year-old successor, Al Mohler, arrived at Southern Seminary greeted by a student body largely wary of his leadership — while one cohort printed hats proclaiming themselves “Al’s Pals.” At a town hall meeting in the seminary chapel, an African student, from a culture that values its elders, bluntly asked, “Dr. Mohler, how do you plan to compensate for your youth and inexperience?”

Without batting an eye, Mohler smiled and calmly said, “I intend to age.” The chapel audience erupted in laughter.

Thirty years later, we can see Mohler was dead serious.

Most painful student remark

I heard from a friend about a conversation with a female Chinese student who asked for an explanation about the tension on campus. My friend told her, “Some folks want a school where there is freedom to ask tough questions and explore answers. Those who are now in the majority on the board want to limit the kinds of questions that can be asked and answers that can be given.”

The woman from China reportedly made a face of both concern and fear and said, “But that is why I left China.”

Brad Bull was president of the December 1992 graduating class at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He has served as a hospital chaplain, pastor and university professor. He now works as a private practice marriage and family therapist in Tennessee and Virginia. His counseling and retreat services operate from DrBradBull.com.

Related article:

Thirty years later, no one has reshaped the SBC more than Albert Mohler | Analysis by Mark Wingfield