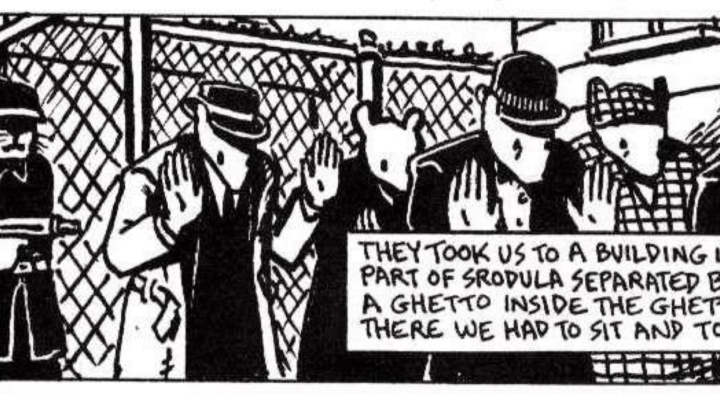

In Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History, the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel, writer and illustrator Art Spiegelman inquires of his Polish Jewish father: “When did you first hear about Auschwitz?”

His father, a Holocaust survivor, replies: “Right away we heard, even from there — from that other world — people came back and told us. But we didn’t believe them. Then this same news came more and more — so we believed, and later on, we SAW, even WORSE.”

Art Spiegelman (Photo by Mark Sagliocco/Getty Images)

Spiegelman utilizes his father’s accounts as a case study for describing the way in which one Jewish family was swept up in the social, political and moral collapse of their homeland, and the evolving Nazi-driven bureaucracy of extermination. Maus documents that saga, detailed in word and picture, with the Jewish characters depicted as mice, their Nazi protagonists as cats.

Spiegelman’s father, Vladek, provides an oral history of his experiences, including the courtship of his wife, Anja, through the process by which Polish Jews were detained and documented in urban ghettos, lied to about their destinations and shipped to “the camps,” some sent immediately to their death and others to deadly work camps.

The Spiegelmans devised an elaborate hiding place in the basement of their home, only to be exposed by a Jewish friend whom they tried to help. Yet Vladek and Anja survived, losing their first-born son, Richlieu, in 1943. Anja Spiegelman died by suicide in 1968; Vladek destroyed her Auschwitz journals.

A Tennessee school board objects

Maus is a powerful addition to Holocaust literature used in a variety of educational venues across the country, yet today’s culture wars know no bounds in the land of the free and the home of insurrections. In January 2022, the 10-member school board in McMinn County, Tenn., voted unanimously to remove Maus from the county’s eighth grade curriculum, “because of its unnecessary use of profanity and nudity and its depiction of violence and suicide.”

The McMinn County School Board

The school board stated that “we do not diminish the value of Maus as an impactful and meaningful piece of literature, nor do we dispute the importance of teaching our children the historical and moral lessons and realities of the Holocaust.” They concluded: “We simply do not believe that this work is an appropriate text for our students to study.”

In many ways, that explanation begs the question. The Tennessee school board focused on Maus at a time when the Anti-Defamation League Audit of Antisemitic Incidents in the U.S. documented more than 2,100 occasions of assault, vandalism and harassment, representing a growth of 12% over 2020, the largest number of antisemitic actions since ADL records began in 1979.

Many of us still recall the 2017 “Unite the Right” event in Charlottesville, Va. when torch-bearing marchers shouted their chilling chant, “Jews will not replace us,” into the Virginia night air. In pre-COVID 2018, ADL also documented 4.2 million antisemitic tweets shared or re-shared on Twitter over a 12-month period.

Likewise, the McMinn board appeared to be more concerned about the book’s eight words of profanity and the small sketch of a nude body — depicting the 1968 suicide of Spiegleman’s mother from Holocaust stress — than the entire mechanism by which multitudes of Polish Jews were murdered. Nor did they account for the presence of teachers who would aid students in sorting out the meaning of the Holocaust then and now.

“The McMinn board appeared to be more concerned about the book’s eight words of profanity and the small sketch of a nude body … than the entire mechanism by which multitudes of Polish Jews were murdered.”

Counter protests were instantaneous. Multiple comics publishers raised funds to provide free copies of Maus to every student in McMinn County, joined by members of St Paul’s Episcopal Church nearby.

And then there’s Texas

These events might not seem so crucial if they were the only censorship game in town, but such is not the case. States across the country are proposing legislation to prohibit or censor schools from readings that might “make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish,” as the current Texas attorney general stated in submitting his list of 850 books recommended for removal.

The Texas Legislature recently approved a new statewide curriculum with a mandate that no system should teach that “the advent of slavery in the territory that is now the United States constituted the true founding of the United States; or with respect to their relationship to American values, slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to, the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality.”

… and Kentucky

In Kentucky, proposed House Bill 14 would mandate that “no public school or public charter school offers any classroom instruction or discussion that incorporates designated concepts related to race, sex and religion; provide that a school district employee that violates the prohibition is subject to disciplinary action; authorize the attorney general to enforce the prohibition; authorize a penalty of $5,000 for each day a violation.”

Joe Phelps

In a response to that action, Joe Phelps, retired pastor of Louisville’s Highland Baptist Church, wrote in an op-ed in that city’s Courier Journal: “Unfortunately, HR 14 … would restrict Kentucky teachers from presenting American history facts about slavery and Jim Crow that might make some white students feel ‘uncomfortable.’ Omit the graphic stories. Ignore new information, like yesterday’s Wall Street Journal report listing the 1,700 elected national leaders who were slaveholders, along with the legislation they passed.”

Phelps accused the legislation of “hiding the whole truth about race in America” and asserted: “Our commonwealth must teach the whole truth to our school children so that they, our future, will have a clearer sense of how we got where we are as a state, and how we might join hands to lift ourselves to higher ground. There is no ‘commonwealth’ in Kentucky without truth.”

These are but a few of the state legislatures moving to enact similar laws, mostly in “red” states, although a certain “blue” state (Washington) school board recently removed Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird as required reading for ninth graders, citing racial insensitivity, but retained it in libraries.

Four things this means

What does all this suggest in 21st century America? I’d suggest four things.

First, books always have provoked controversy in American public education, as evident in Tennessee laws against teaching evolution, and the resultingly infamous Scopes Monkey Trial. Yet the recent rash of textbook-related legislation is yet another sign of our deep national divisions, the rabid politization of an entire culture, and with no end in sight. It often appears that legislatures are less concerned about education than about, as the saying goes, “appealing to their base.” The removal of Maus seems a case study in a much broader agenda.

“Confronting segregation and civil rights in Sue Coffman’s English class at Paschal High in Fort Worth changed my life from 1964 to this very moment.”

Second, efforts to limit or discourage use of “designated concepts related to race, sex and religion,” particularly because they may undermine some mythic identity of the nature of this Republic, rob students and teachers alike of the opportunity to engage the “hard topics” in a safe environment. Confronting segregation and civil rights in Sue Coffman’s English class at Paschal High in Fort Worth, Texas, changed my life from 1964 to this very moment. Are such race-related transformations now impossible in the Lone Star state?

Third, that assorted school systems seek to prohibit texts or topics that might “make students feel discomfort, guilt or anguish” seems ironic, especially in Southern states where at least some legislators surely identify as “evangelical.” Those faith communities instruct children early on that they are, from creation, bound to a perpetually tainted human race, since “in Adam’s Fall we sinned all.” In childhood, the doctrine of original sin gave me considerable “discomfort, guilt or anguish” before I ever got to the relatively unoriginal sins of “race, sex,” and certain kinds of religion.

Finally, is it just me, or does it seem strange that so many of the books singled out for removal come from Jewish, African American, or yes, LGBTQ authors? For many state legislators, perhaps that’s just part of “the art of the deal.”

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

It was fundamentalists who taught me about soul competency, and now they want to ban books? | Opinion by Susan Shaw

That time I went to the school board meeting to speak against banning books | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

From Texas to Tennessee, evangelical parents are trying to take the ‘public’ out of public education | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Is it now illegal to mention the Tulsa Race Massacre in the classrooms of Oklahoma? | Opinion by Alan Bean