Sixty-two years ago this spring, Martin Luther King Jr. famously preached in chapel at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky. The date was April 19, 1961.

What is less remembered is that King also spoke that day in a Christian ethics class taught by Henlee Barnette, a preeminent ethicist who was responsible, in part, for inviting King to the seminary campus. Interest in attending the class — which included a Q&A with the great civil rights leader — was so great that the location was changed three times, ultimately landing in the largest room on campus, Alumni Chapel.

For context on this moment: John F. Kennedy had been inaugurated as president of the United States just three months earlier. According to the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University: “King’s high expectations for the new administration gave way to disappointment as the president hesitated to commit to comprehensive civil rights legislation. As the initial Freedom Ride catapulted King into the national spotlight in May, tensions with student activists affiliated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) were exacerbated after King refused to participate in subsequent freedom rides. These tensions became more evident after King accepted an invitation in December 1961 to help the SNCC-supported Albany Movement in southwest Georgia. King’s arrests in Albany prompted widespread national press coverage for the protests there, but he left with minimal tangible gains.”

Martin Luther King Jr. at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in 1961, shown here with professors (from left to right) Henlee Barnette, Nolan Howington and Allen Graves. (SBTS photo)

Just days before his speech in Louisville, King had given one of the most important speeches of his early career to save an agreement to end a student boycott in Atlanta. The Civil Rights movement in Atlanta was at full tilt and foreshadowing what would happen across the American South.

It was only a year before his appearance at Southern Seminary that King had become co-pastor with his father of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. Also the year prior, lunch counter sit-ins began in Greensboro, N.C., and King himself had been arrested during a sit-in while waiting to be served at a restaurant. He was sentenced to four months in jail but was released after intervention by John F. Kennedy and Robert Kennedy.

‘A spiritual movement’

In the midst of this moment — two years before King wrote Letter from a Birmingham Jail and before his “I have a dream” speech — King talked with the integrated but still mainly white Southern Seminary students about his nonviolent protest methods and the cause of human dignity.

He framed this work as a “spiritual movement.”

Although his chapel sermon had been more staid and academic, his classroom lecture and student interaction showed the orator’s great way with words.

King began by telling the seminarians he saw three possible ways oppressed people could respond to their oppression.

Acquiescence

One way is “to acquiesce, to resign oneself to the fate of oppression,” he said. “And this method has been used through history. You remember when Moses was leading the children of Israel out of Egypt and toward the Promised Land, and they got out into the wilderness. There were some who wanted to go back to Egypt. They preferred the fleshpots of Egypt to the challenges ahead.

“Non-cooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as cooperation with good.”

“I remember when I was coming up in Atlanta, there was a man who used to play a guitar, and he had favorite songs he would sing. And one day, I discovered he was singing a little song like this, ‘Been down so long that down don’t bother me.’ Now, a lot of people get to this point. They achieve the freedom of exhaustion. And … this isn’t the way, because non-cooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as cooperation with good.”

Hatred and violence

The second method King cited was “corroding hatred and physical violence.”

This method “has been something of the inseparable twin of Western materialism and the hallmark of its grandeur,” he said. But it only brings about temporary victory.

“Although it may bring about temporary victory, it never brings permanent peace, and violence ends up creating many more social problems than it solved,” he explained.

Nonviolent resistance

But there is a third way, he continued: “non-violent resistance. And this is a method which makes it possible for the individual to stand up against an unjust system, to resist that system, and yet not hate in the process, and not use violence in the process.”

That, of course, was the method for which King became best known and that became a hallmark of the Civil Rights movement.

“It gives one the possibility of working for moral ends through moral means.”

“There are many things that can be said for this method,” he told the seminarians. “First, it gives one the possibility of working for moral ends through moral means. And this is where nonviolent resistance would break with all those systems that would argue the end justifies a means.

“I remember some time ago when the student movement first started, a former president of the United States, the only thing he could say about it was that it was communist inspired. And I’m sure the students all over were very insulted by that. So, No. 1, it’s an insult on one’s intelligence to say to him that if somebody is standing on his neck, he doesn’t have the intelligence to rise up against this and protest unless Mr. Khrushchev from Russia comes over and tells him that somebody’s standing on his neck.

“But the other reason is even deeper than that, that is, this is a spiritual movement. It has a spiritualistic worldview rejecting the materialistic worldview of communism and also rejecting the ethical relativism of communism.”

King quoted Vladimir Lenin who said “any method is justifiable in order to bring about the classless society. So he says, lying defeats violence, anything just as long as it brings about the classless society he talks about. But in the method of nonviolence resistance, when one is committed to it as a way of life, he does not succumb to the temptation of believing an immoral means can bring about moral ends, because he realizes the end is preexistent in the meaning. And the method of nonviolence makes it possible for one to seek to secure moral ends through moral means.”

“The method of nonviolence makes it possible for one to seek to secure moral ends through moral means.”

Those committed to nonviolence in the Civil Rights movement, he said, seek to “defeat segregation and not the segregationist. He seeks to convert the segregationist. And this is the tragedy of violence. You see, it seeks to annihilate the opponent rather than convert the opponent.”

Rooted in Jesus

King said the violence of which he spoke was not just physical violence but “internal violence of spirit.”

To illustrate nonviolence, he cited Mahatma Gandhi, “who used this method in a magnificent way to free his people from the domination of the British Empire,” being “greatly influenced by the Sermon on the Mount. He read the Sermon on the Mount. He said this was one of the most moving experiences of his life, particularly the part that says turn the other cheek.”

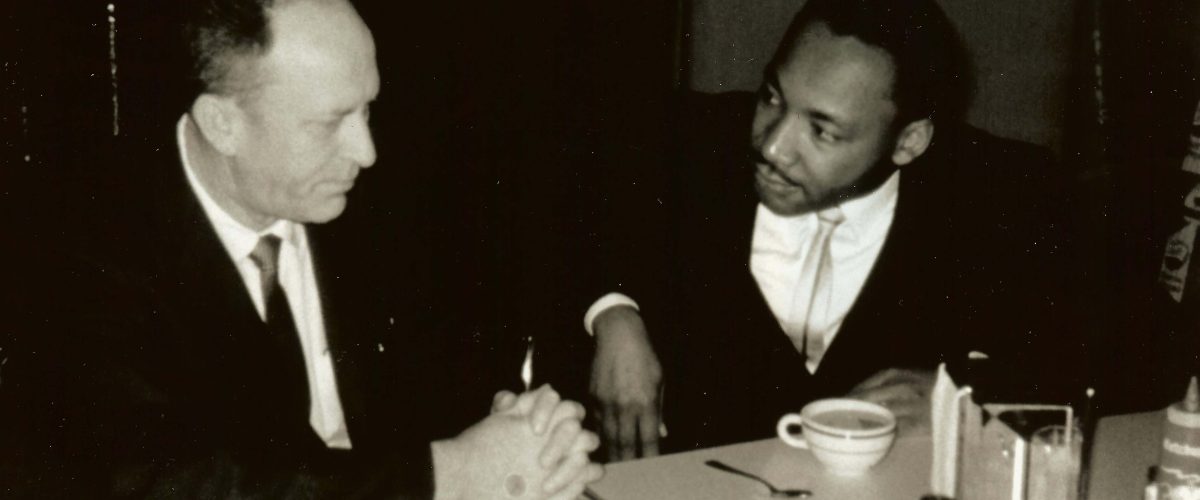

Martin Luther King Jr., while visiting Louisville in 1961, shares coffee with John Claypool (second from left) and others. Claypool was pastor at Crescent Hill Baptist Church.

Just as Gandhi, who was not a Christian, was influenced by the teaching of Jesus, so the Civil Rights movement was influenced by Jesus, King said. “When we started our movement in Montgomery, Ala., long before the people heard the name of Mahatma Gandhi, they had heard of Christ. And we made it very clear this was a movement of Christian love. This was a movement based on the Christian ethic of love. And this is why I say our movement there received this spirit and its inspiration from Christ and its operational technique from God.”

Nonviolence, then, finds it roots in Jesus of Nazareth, the Baptist preacher asserted.

Good in human nature

Finally, nonviolence teaches “there is an element of good that is there, amazing potentialities for goodness within human nature. And that it is possible for human beings to be transformed. This is basic in nonviolence.”

Believing in such potential for transformation does not demand superficial optimism, King continued. “At times, those who have believed in nonviolence have been a little too superficial in the optimism concerning human nature. Man is not all good. There is some bad in him. … It’s not enough to just say that man has potentialities for goodness. We must say man has potentialities for evil also and be realistic in our anthropology.

“So I don’t want to give anybody the impression that in order to believe in this philosophy of nonviolence, it is necessary to go to the extremes that even liberalism within Protestantism has often gone to, of seeing man evolving up some ladder of goodness that will finally be worked out in the long run of things. The fact is that we have too much evidence to refute this.

“But man does have potentialities for goodness as well as potentialities for evil, and the nonviolent resister believes these things can be brought out, and that the image of God is not totally destroyed, man is not totally depraved. Although the image is terribly scarred, there is a possibility to transform human nature.”

Are sit-ins nonviolent?

During a question-and-answer time with students, King addressed a question about whether the student sit-ins that were happening at the time were violent or nonviolent.

“The intent is to put justice in business and really to make a better business.”

“I have never seen the boycott as a violent method,” he answered. “Certainly those who use it are not participating in physical violence. … We stress the need for loving and maintaining this, understanding goodwill so that the intent is not to destroy, not to put anybody out of business. The intent is to put justice in business and really to make a better business. Because if these barriers are broken down, these merchants will make more money.”

Sadly, he noted, the racist systems of the South were so entrenched that businessmen would rather take financial losses than serve Blacks. They preferred maintaining an unjust system to growing their businesses.

The boycotts, he said, were not intended to put anyone out of business. They were, instead, “a massive withdrawal of support from a system of evil in order to bring about some ultimate change and transformation. And certainly we hope we will convert some of the merchants in the process. … Now, we know that some people, as a result of boycotts, suffer on both sides. In Atlanta, when we had the boycott, 300 and some people lost their jobs. … I mean, Negro people who worked at these lunch counters. And this is something of the risk and something of the temporary sacrifice you must go through in order to bring about the social change and transformation we are seeking.”

Just and unjust laws

Another student asked whether Christians are required to obey all laws.

King responded: “There are two types of laws. There are just laws, and there are unjust laws. I would be the first person to say to everybody, obey just laws. Now that just puts us into the position of asking what are just laws? And what are unjust laws? I would say a just law is a law that squares with the moral law of the universe. A just law is a man-made law that is in line with what the religionist would call the law of God.”

“I would say a just law is a law that squares with the moral law of the universe.”

On the other hand, unjust laws occur “when the majority imposes a code on the minority that the minority has no part in creating or an enacting, because that minority has no right to vote. So the legislatures of most of the states in the Deep South are not even democratically elected.”

The Christian, King said, “not only has a right, but a responsibility to stand up against an unjust law. But now, in doing this, he must do it peacefully. He must do it nonviolently. He must do it in a loving spirit, and he must be willing to accept the penalty. He must not speak to evade the law. He must not seek to subvert the law. He must do it openly. He must not seek to defy the law, because he becomes an anarchist then. But the individual who decides to break a law that conscience tells him is unjust and willingly, cheerfully and voluntarily accepts the penalty, is at that moment expressing the very highest respect for law. And he is not an anarchist, but he’s expressing the very highest respect for law.”

Those who defy unjust laws and are willing to go to jail for the cause of justice and “arouse the conscience of the community” are “expressing the very highest respect for law,” he said.

He gave the seminarians multiple historical examples of people who were justified in defying unjust laws — from the early church, to the Boston Tea Party, to the Underground Railroad, to Germans under Hitler, to Hungarian freedom fighters, to those who opposed apartheid in South Africa.

“The students today in disobeying laws they know are unjust are really in noble company. They are in the company of people throughout history,” he said.

One challenge of the fight for civil rights in America is that “our struggle in America is not driving a foreign invader out, but it’s seeking a new level of creative life and existence with the very people you’re going to have to live with. The very minute the struggle ends, you’re going to have to live with these same people tomorrow morning. … In our situation, it is even more imperative to practice nonviolence, because we have this job of living with the very people and being friends with the very people we are struggling against at this time.”

Extremism

Asked by another student about “extremism,” King replied: “I believe in the extreme of love, not the extreme of hate. I believe in the extreme of goodwill, and not the extreme of ill will. I’m never worried about being an extremist. I think the world is in great need of extremism.”

“He should not have the freedom to choose his customers on the basis of race or religion.”

Near the end of the hour, King was asked about race and religion.

He replied: “On the basis of race and religion, I don’t think America will ever rise to its full maturity until all over this country we say that anybody who’s in a public business cannot deny anybody on the basis of race or color access to that business. He should not have the freedom to choose his customers on the basis of race or religion. This has really taken freedom too far.”

Related articles:

Southern Seminary won’t rename buildings but creates scholarships for Black students

Baptist Calvinists defend slavery of Southern Seminary founders