This is the second of a four-part series in which we seek to see anew the incarnation of Jesus through the eyes and body of a woman, Mary the mother of Jesus.

For Jesus to become flesh, word incarnate, he had to be born. Like each of us, his journey began in the body of a woman. His flesh had to enter the world through the waters of the birth canal of a woman named Mary.

Her labor most likely was long as it was by all accounts her first child and she had not pushed a child through her body before. Women can prepare all we want, but nothing can truly prepare us for the violence, pain, fear and unpredictability of birth.

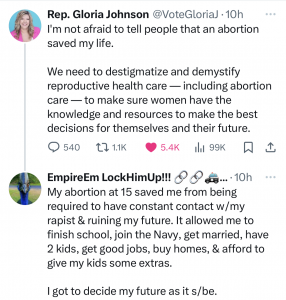

“Still Water” by Amanda Greavette 48x36in 2013 featured in 2016 Huffington Post article

It is amazing what our bodies can do, yet they are incredibly fragile. Things can go wrong so very quickly. We can die in childbirth. Even with all we know about maternal care, mortality rates in the United States are still frighteningly high for a developed country compared to our counterparts. Flesh is fragile. Flesh opens us up to pain.

“You were unmindful of the Rock that bore you; you forgot the God who gave you birth” —Deuteronomy 32:18

Phyllis Trible writes of this passage, “We need to accent the striking portrayal of God as a woman in labor pains, for the Hebrew verb has exclusively this meaning.”

Jann Aldredge-Clanton says the Hebrew verb from this verse is accurately translated “bore,” not “fathered” as it has often been translated in the past. “Over centuries, translators and commentators have ignored such female imagery, with disastrous results for God, man and woman. To reclaim the image of God as female is to become aware of the male idolatry that has long infested faith.”

God bore us in pain, she labors to create, to bring forth new life in her fruitful strength and glory.

Detail of The Virgin and Child in Majesty. Attributed to the Master of Pedret. Spanish, Catalonia, 12th century. Date: ca. 1100. (Wikimedia)

The pain of women is familiar to God.

The pain of childbirth is not just that it hurts, and it really does hurt badly, it is that it keeps going and going with little relief. The duration, the length of the pain, is what is so hard to bear. It intensifies, and the longer it continues the harder it becomes to endure. Any man who has seen a woman giving birth and still thinks women are the weaker sex needs to re-evaluate their own so-called strength.

We do not know if Mary had a specific birth plan or access to any pain relief methods or medicines. A birth plan was what each woman has done before — repeatedly with wisdom passed down from generation to generation, familial support and midwifery. We do know women in Mary’s time and region typically would rely on female family and community members to assist with the birth. It would be a home birth, as younger couples typically would have small quarters within larger intergenerational family homes.

If it was Mary’s plan to give birth at home, it was abandoned if the birth scenes in the Gospels are to be taken literally. Mary traveled without any family support on a long journey to be counted in a census with Joseph. Scholars point out it would have been unnecessary for the women to accompany the men to be counted. Literary device or not, the nativity scenes of Mary with the babe Jesus laid in a manger in the stable or cave having just arrived in Bethlehem should give us pause in imagining how a birth could have taken place just moments before.

Robert Campin, c. 1420, Nativity. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon. This Netherlandish nativity painting tells a little known story of Joseph summoning two midwives to attend Mary.

I do not see any blood or placenta in our Christmas card scenes. Midwives? Cloths or warm water for cleaning? Anyone or anything to help with the birth? Not in the picture. Seems like Mary was alone, with only Joseph to assist with the birth.

My birth plan also was abandoned. The first time I gave birth, I was well past my due date, so I was induced when I began to show some signs of labor with minor contractions. My labor and dilation did not progress significantly, so I was given the drug Pitocin intravenously. Unfortunately, I had a hyper reaction to the drug and almost immediately was in mind-numbing pain. I do not remember much that happened in the next 45-minute period but my spouse reports some thrashing around in the hospital bed and that the hospital staff quickly backed off the drug until they could get the anesthesiologist to give me an earlier than usual epidural. I nodded assent, scribbled my signature, and was able by that time to hold still enough for it to be administered.

Perhaps because I had the epidural so early in the labor trajectory, I continued to progress slowly and not without complications. Leads were attached to our baby’s head to monitor the heartbeat; meconium was present risking breathing issues, airway blockages and infection. A C-section was considered, but I fought the doctor off long enough for a little more progress to happen and they allowed me to push — but with the caveat that forceps might be necessary to get the baby out quickly.

Thankfully, my spouse and I had attended a series of classes led by our pediatrician who prepared us for all that could go wrong with the baby during labor and delivery. Finally, I pushed the baby out. Our first child was born (with a course of antibiotics on board for us both in case of infection).

Julia Goldie Day

What I was not prepared for is how to advocate for myself. How I would feel alone and afraid for my life and the life of my child even with a supportive spouse in the room (who also did not know what to do for me). How I was risking death. How I would need to heal. The trauma of birth is not discussed well enough with those who are able to give birth. I advocated well for my child but not for myself. It seemed as if I was an afterthought.

In the best-selling novel by Bonnie Garmus, now an Apple TV series, Lessons in Chemistry, main character Elizabeth Zott (played by Brie Larson) enters the hospital to give birth to the child she conceived with her recently deceased chemistry research partner and lover. She already is distrustful of men and institutions, having been fired from her job because she was pregnant. Knowing she had no access to birth control (it was the 1950s) or abortion, fair access to employment or education, her research had been stolen, her life in shambles, her loving and brilliant partner dead, no family support, alone in a hospital and quoted the price of pain medication she cannot afford, Elizabeth gives birth.

A chipper nurse comes along and says she should name her child the emotion she is feeling, assuming it is a pleasant one such as “Joy.” Elizabeth names her child “Mad.” Mad is the name on the birth certificate.

When I was in the hospital giving birth to my second child, the nurse told me I could not begin to push because there was another woman who was closer to giving birth than I and my doctor — who was not even in the building yet — would be attending to her first. I sat in shock for a moment after she left the room. After 30 minutes or so had passed of me trying not to push, I told my spouse he needed to find someone because I was pushing already, whether they were ready or not. They got ready. I pushed without the doctor. He showed up just in time to deliver the baby, but at that point I did not care if he was there or not.

We are asked somehow to forget that we are powerful, that we should not in fact listen to ourselves, that our pain is not important, that our bodies aren’t important.

It makes sense that we are angry. We cannot make choices about our own bodies, or we are forced to bear pain we are not ready to bear.

Many of us are forced to bear children our bodies and minds and are not ready to bear — especially when we are children ourselves, the 11-year-old victims of rape, children birthing children, forced to give birth. That is inhumane. It is torture.

Many of us are forced to bear children our bodies and minds and are not ready to bear — especially when we are children ourselves, the 11-year-old victims of rape, children birthing children, forced to give birth. That is inhumane. It is torture.

How could we say this body belongs to anyone else or a fetus produced by this body belongs to anyone else?

Here is the sin, the problem in the abortion ban. We have tried to make the bodies of women and girls disappear.

In our Advent observances, we have tried to make Mary disappear and only see Jesus, but we would not have Jesus without Mary.

Thomas Merton writes this about Mary, “She crowns him not with what is glorious, but with what is greater than glory: the one thing greater than glory is weakness, nothingness, poverty.”

What even the most thoughtful church fathers miss is that Mary crowns Jesus with her body.

With her body Mary persists in love. Continuing despite the pain. That is love. That is power. The creative power of labor and pain pushes toward the end goal of life. We sacrifice, we persist because we love; we have faith despite our despair, despite the pain. We speak life into existence with our groaning bodies. Amen.

Is it possible that through our Western patriarchal eyes we see women so poorly, so horribly, that if we can see a woman as creating the Holy of Holies, Jesus, we would be truer to Scripture, more faithful in our anticipation of Emmanuel?

For Mary’s body speaks of the good news of great joy that is coming.

So next time you hear or sing “O Come, All Ye Faithful,” if you are brave enough, picture the head of baby Jesus crowning from his mother’s body, “now in flesh appearing! O come, let us adore Him, Christ the Lord.”

God of God, light of light,

Lo, he abhors not the Virgin’s womb;

Very God, begotten, not created:

O come, let us adore Him,

Christ the Lord.

Yea, Lord, we greet thee, born this happy morning;

Jesus, to thee be glory given!

Word of the Father, now in flesh appearing!

O come, let us adore Him,

Christ the Lord.

(Adeste Fideles partial translation of original Latin verses published in 1751 by John Francis Wade)

How we see Advent through the eyes, through the body of Mary, colors our experience anew:

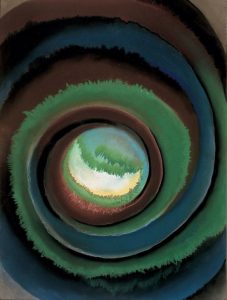

Pond in the Woods by Georgia O’Keeffe, 1922, Pastel on paper, 24 x 18 inches, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Blue waters of wisdom. May words from the deep, the muddy blue waters of birth rise to the surface and give us deeper wisdom. We should not make an idol out of pain; suffering is not necessary for women or any person to be redeemed. Pain is not glorified but respected and prevented (or reduced) when possible.

Love is necessary. Love cries out for justice when women suffer and die in childbirth, when infants are stillborn for no known reason, when infants die from complications that could have been prevented with medical care, when 11-year-olds are forced to give birth to their rapist’s baby.

Our hearts are broken when children die in bombings in senseless wars. This kind of unspeakable pain causes us cry to out to God for mercy and to work for a more just world for women and children and for all people.

Blue waters of reflection. Cleanse us from our unbelief, from our inability to see the pain of women and the strength of women. Forgive us for missing the beauty of the incarnation in a woman’s body. Give us eyes to see, to rejoice in spite of pain, in the midst of pain, groaning for peace on earth. May it be so. Amen.

But when the fullness of time had come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, in order to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as children. — Galatians 4:4-5

All day, every day, therapist, mother, maid

Nymph then a virgin, nurse then a servant

Just an appendage, live to attend him

So that he never lifts a finger

24-7, baby machine

So he can live out his picket fence dreams

It’s not an act of love if you make her

You make me do too much labor

— Labour by Paris Paloma

Julia Goldie Day is an ordained minister within the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and lives in Memphis, Tenn. She is a painter and proud mother to Jasper, Barak and Jillian. Learn more at her website or follow her on socials @JuliaGoldieDay.