Recently during worship, my minister sang a song of lament he composed about the whitewashed history of violence and slavery in the United States. In “This House,” Aaron Austin sang: “They said it was history, time to move on. They said things were better and leave it be. But stolen blood still runs through these walls, and the floors still creak with captive feet.”

When I heard those lines, I ran out to my backyard and wept because I have been researching Baptist history in Texas. Texas’ history with slavery has reentered the public eye with arguments over how central slavery was to the Texans’ push for independence from Mexico. Texas also represents one sample of the wider complicity of Southern Baptists, from which I trace my own roots, and other white Protestant denominations with slavery in Texas and throughout the South.

During the 19th century, Texas Baptists believed, in the 1866 words of F.M. Law, “Southern men are, and will be for all time to come, the lords of the Southern soil.” Firmly entrenched in that conviction, Texas Baptist leaders spread a gospel thoroughly tied to plantation hierarchy. They claimed “stolen blood” to be the way God built their orderly, godly, white society. They claimed “captive feet” were the foundation of God’s plan to evangelize the Black populations among them and all of Africa. With these claims, Texas Baptist leaders concocted and promoted evangelism programs to keep the plantation hierarchy alive —t o keep Black people subordinate to white society.

During the Antebellum period, Baptist missionaries and families, along with their slaves, immigrated to Texas and organized churches. They broke with the North to become Southern Baptists in 1845 and started various self-governing regional associations and two state conventions: the Baptist State Convention in 1848 and the Baptist General Association in 1853.

“Before and during the Civil War, white Texas Baptist leadership tied their theology of the gospel and plans for evangelism directly to Southern plantation patriarchy and support of the Confederacy.”

Before and during the Civil War, white Texas Baptist leadership tied their theology of the gospel and plans for evangelism directly to Southern plantation patriarchy and support of the Confederacy. In the 10 years following, known as Reconstruction (1865-1875), Texas Baptists adapted their plantation evangelism to maintain their religious authority over Black freed persons. Texas Baptist association leaders instructed their pastors and missionaries to go and preach a gospel that instructed Black worshippers, preachers and institutions to serve white society, and they claimed this was God’s providential design. Black worshippers and church leaders refused this gospel and left white churches for Black-led denominations, even though they risked rebuke, slander and even murder from the white society the Texas Baptist leadership continued to commend.

This essay may come as a shock to some, especially the descendants of white Texas Baptists and other Southern Baptists. Others, especially Black Christians in Texas and across the South, may know this history very well. For the rest of this essay, I will recreate a timeline of these years to demonstrate how the rise of Black churches, violence against Black people and their communities, and the Texas Baptist associational reports coincide to show the continued white patriarchal mindset and the violence of the Texas Baptist plantation evangelism plans.

The Equal Justice Initiative report on Reconstruction, whose data on lynching I quote below, estimates that 2,000 Black victims were murdered in acts of racial terror across the United States from 1865-1876. All the Texas Baptist reports I reference below were published in James M. Carroll’s denominational history, A History of Texas Baptists (1923). I will continue to call white Baptists in Texas the “Texas Baptists” because that is how they labeled themselves. As you will see, even their label is problematic because they used their self-identity to exclude Black Baptists and undermine Black Christianity.

Plantation evangelism in the Civil War

Anderson Buffington

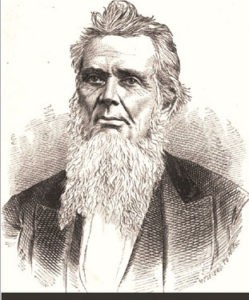

Before the Civil War officially began, white Texas Baptists adamantly spoke of their mission to uphold the sanctity of plantation order through evangelism to slaves. In 1856, A. Buffington, speaking to the Texas Baptist State Convention, declared that the “original design of the importation of Africans to Christian shores of America was purely to Christianize them.” He then called “the fanatical and blinded Abolitionist” a “tool of Satan to produce discord and disunion” to their “holy mission of leading the Sons of Ham to the cross of Jesus, and thus prepare them to become ‘obedient to their masters’ and to become ‘heirs of God and joint heirs with Jesus Christ.’” Texas Baptists charged missionaries and pastors, including B.H. Carroll’s father, Benajah Carroll, to preach and baptize in the plantations, especially along the Brazos River.

Pre-Civil War, there were a few separate Black Baptist congregations, like First Africa Church of Galveston (est. 1840) and Ebenezer Baptist in La Grange (est. 1860). They remained under strict Texas Baptist oversight.

Elder Jonas Johnston reported, in 1857, that in the few places where Black slaves were organized into separate congregations, white ministers presided or attended over worship. As the civil war neared, white Texans increased their violent treatment of slaves and suppressed all public gatherings of enslaved people, even those where white men attended. In 1860, for example, white citizens lynched 30 to 50 slaves and possibly 20 or more white people in North Texas due to rumors of Union sympathy and insurrection. S.G. O’Bryan, at the 1861 Union Association, blamed “political excitement” among the slaves when he defended white Baptist suspension of separate Black worship in areas around Houston.

Texas Baptist convictions about the moral superiority of slavery continued during the Civil War, even as white Texans continued to lynch slaves and suspected Union sympathizers. In 1861, T.P. Aycock urged the churches of the Waco Association “to do all they can” so that Texas Christianity may “vindicate our social system as not inconsistent with civilization, but as the appointed means by which Ethiopia shall stretch out her hand to God.”

G.W. Baines

At the 1862 Baptist State Convention, George W. Baines Sr. interpreted the Civil War as God’s anger toward the slave-masters among Texas Baptists, but then said, “as it cannot be wrong to own slaves, may it not be that much of our present deep affliction is a manifestation of God’s displeasure against us for our neglect to furnish the slaves among us the means of gospel grace?”

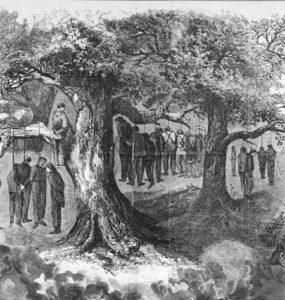

Gainesville hanging

Later, in October 1862, self-appointed vigilantes lynched 41 people in Gainesville, a town near the Texas/Oklahoma state line. The Texas Baptist leaders never mentioned Gainesville or any other violence toward Black slaves in their reports, except to wring their hands and vaguely discuss suppressing Black worship and the danger for white men to be seen among Black crowds.

In 1863, Texas Baptist reports began to reflect open concern for the Confederate Army and share disdain for Northern sympathizers too. The Texas Baptists raised almost $10,000 to send missionaries to the Confederate Army with an appeal to fund “the man of God” ministering to the Confederate soldiers “toiling for your liberties.”

W.I. Albright, in a report to the Little River Association, blamed the North’s “interference … under false pretense of friendship” for the slave owner’s need “to be more rigid in our discipline towards our slaves.” Also blaming the North, S.I. Caldwell recommended pastors specifically instruct all Black slaves that “slavery is scriptural,” and that “when they join the Federals they absolve the obligation of the master to protect and defend them, and they will be treated by the South as enemies of the Confederate government.”

Like a broken record throughout the Civil War, Texas Baptist State Convention and regional association reports continued to argue, like that of Z.N. Morell in 1864, that Southern slaveowners had an “especial” responsibility to Black slaves to “give them proper ideas of their temporal relations” between master and slave, and “clear conceptions of their responsibilities to God.”

Texas Baptist evangelistic preaching about salvation included slave obedience; the two ideas were tied together under Texas Baptist belief in God’s providence.

Plantation evangelism during Reconstruction (1865-1875)

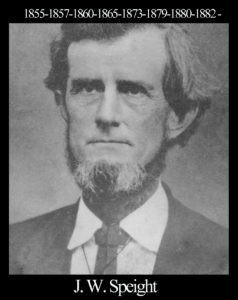

J.W. Speight

The United States federal dissolution of slavery after the end of the Civil War did not end violence against Black men, women and children, nor did it dissolve the bonds between Texas Baptist evangelism and the plantation. In 1865 and 1866 near Sherman, Texas, a white man shot Thomas Daniels for doing his work wrong, and another white man shot Jack Stone for not tipping his hat. In 1866 near Temple and Killeen, Texas, the Ku Klux Klan attacked and killed at least seven Black people, while in Fannin County white men shot at a group of Black people on their way to see a show, killing three and wounding many more. A Freedman’s Bureau official from Sherman reported in 1866, “the freedmen here have been kept in perfect terror of their lives.” And yet, in his 1865 report to the Waco Association, J.W. Speight dismissed any need to discuss the political change in the status of Black people as freed persons, even as he blamed the North for cutting the former slaves “loose from that restraint and wholesome discipline which has heretofore been a safeguard and security against the exercise of the worst passions of the human breast as exhibited in the untutored and uncultivated mind.”

As Black freed persons were openly terrorized, white Texas Baptists worried about possible violence against themselves.

Along with their concerns for personal safety, Texas Baptist leaders recommitted to evangelizing Black freed persons in order to uphold what they viewed as the moral religious leadership, and also the dominant status, of white society.

In an 1865 Union Association report, F.M. Law and others claimed: “The slaves of the South are not prepared for the change that has taken place. They are not in a condition, it is feared, to be profited by freedom.”

“They are not in a condition, it is feared, to be profited by freedom.”

In an 1866 report to the Baptist State Convention, F.M. Law reported, “even the religious ones among them are, in too many cases, moved rather by impulse and superstition.” Law recommended Texas Baptists commit to Black freed persons “mental and moral elevation … Their temporal and spiritual interests require it. The welfare of the white also demands the same thing.”

In at least 10 reports over the period from 1865 to 1866, Texas Baptists repeatedly described Black freed persons as inferior in mind, indolent, childlike and superstitious as they presented reasons for enlarging evangelistic concerns among the Black population.

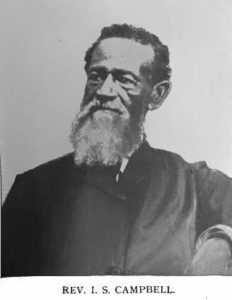

Black freedmen and women were increasingly able to have their own churches and religious institutions outside of white oversight after the Civil War. In 1865, African Methodist Episcopal Church missionaries Michael M. Clark and Houston Reedy arrived in Texas. Reedy organized a church in Galveston that claimed 3,000 members by 1868. Israel S. Campbell, a Black Baptist missionary, moved from Louisiana to Houston and organized Antioch Baptist Church with pastor I. Rhinehart.

Texas Baptists resisted Campbell’s leadership and refused his authority, including his ordination. When Campbell and Rhinehart appealed to the Union Association to dissolve the oversight of the white Baptist church and to receive Antioch as a member congregation, the white association denied their petition. Citing imprudence “under existing circumstances,” the association recommended Antioch Baptist submit to white delegates and adopt the articles of faith from First Baptist Houston.

Galveston Texas Baptists and others in the Colorado Association voted to refuse membership to separate Black Baptist churches because they did not believe Black congregants had sufficient intelligence to learn the Bible and keep doctrines and ordinances “when unaided by whites,” and they did not want to admit ordained Black ministers into their association at all. Undeterred, Antioch Baptist of Houston left the Union Association, and Campbell later moved to Galveston and reorganized First African Church as the First Regular Missionary Baptist Church in 1867.

I.S. Campbell

Meanwhile, violence against the Texas Black population continued and increased in 1868-1869 during the months leading up to and following the presidential election of Ulysses S. Grant. The year 1868 began well for Black Baptists and the AME. Black Baptists organized 20 churches into the Regular Missionary Lincoln Baptist Association and elected Israel Campbell as moderator. The African Methodist Episcopal Church met in Galveston and elected its first bishop as an organized Texas Conference.

In July, however, white mobs killed 150 people and expelled the Black community from Millican, near College Station, because a local Black preacher began organizing the community against white violence. After the massacre in Millican, freedman Joe Easley of Sulphur Springs, Texas, responded, “The reign of terror is set up in this county.” A worker for the Freedman’s Bureau office called the scene “the most sickening sight I ever witnessed to see.”

Violence from Louisiana also affected Texas, as white mobs around Shreveport, La., near the Texas state line, killed 215 Black people over the month of October to suppress Black voting. In April 1869, a white crowd lynched five Black men, including two preachers, in the East Texas town of Henderson with no trial. Many more lynchings, beatings and other acts of terror by white Texans occurred throughout the remainder of Reconstruction to suppress Black voting and to reinforce white supremacy.

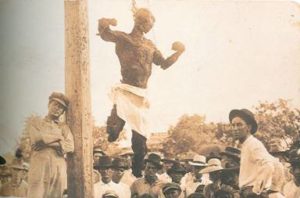

Jesse Washington was lynched and his body burned in public in Waco, Texas, on May 15, 1916. The 17-year-old illiterate farmhand was accused of raping and then bludgeoning to death 53-year-old Lucy Fryer, the wife of a white farmer in Robinson, a small community seven miles south of Waco.

Texas Baptist reports never mention or condemn any of these acts of violence, not even when Black pastors are killed. Instead, Texas Baptists reports on their religious work among Black freed persons primarily complain about Black separation from their congregations and degrade Black worship and ministry leadership.

The 1868 Cherokee Association report, whose East Texas churches included Henderson and bordered Shreveport, La., stated that “their condition is truly deplorable, with few exceptions they are holding meetings to little or no profit. Very few white preachers are now preaching to them regularly.” By 1870, many associations agreed and started blaming Catholics, Northerners and Black preachers for what Texas Baptists saw as bad doctrine, unruly worship and resistance to their white preachers.

The Austin Association claimed Catholics and Northerners were “taking advantage” of Black freed persons and stirring “prejudices … among both whites and blacks.” The Union Association accused Black missionaries and preachers of clothing “themselves in the garb of Christianity, for political purposes, and thus become promoters of strife, ill will and prejudice, rather than of love, peace and truth.”

In 1871, D.D. Foreman told the Tryon Association that Black ministers, “as a body, are entirely illiterate, consequently their teaching is a work of wild, ungoverned imagination.” All of these associations overlapped territories with the Black Baptist Lincoln Association and included places of terror like Millican and Henderson. These reports may have justified or stirred up more terror against missionaries like Israel Campbell and other Black churches throughout Texas.

First Baptist Church of San Marcos, Texas.

Throughout these years of white Texas Baptist denigration of Black spirituality, Black churches of all denominations continued to grow. By 1871, the Methodist Episcopal Church listed almost 8,000 Black members and 51 ministers, and Black Southern Methodists had established a separate denomination, the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1872, the AME established Paul Quinn College in Austin, and in 1873 the Methodist Episcopal Conference founded Wiley College in Marshall for Black higher education.

By 1875, the AME Church grew large enough to organize its second Annual Conference in West Texas, and Black Baptists held their first statewide convention meeting. However, in 1872, Congress rescinded protections when it dismantled the Freedman’s Bureau. In 1873, G.W. Schobey, a lawyer and teacher in Black schools, was gunned down by two white men to prevent his election to the Legislature. Black churches grew in Texas in spite of continued violence against Black freed persons and white sympathizers.

Texas Southern Baptist leaders refused to acknowledge the majority of Black Christianity as legitimate and insisted only white Baptist preachers were well-trained to preach the correct gospel. But by 1872, Texas Baptist leaders no longer could deny the existence of these Black denominations. The San Antonio Association report begrudgingly admitted that several Black Baptist churches and a local Black Baptist Association existed within their territory, although it still claimed, “the masses are exceedingly deficient on intellectual training, making it very difficult to reach them with the gospel.”

“The masses are exceedingly deficient on intellectual training, making it very difficult to reach them with the gospel.”

Later that year, B.H. Carroll, as committee chair, signed and authorized a Texas Baptist Convention report addressing the concerns laid out by these regional associations. Invoking theological language similar to T.P. Aycock’s Civil War language to provoke evangelistic mission to the slaves, Carroll’s report proclaimed God would bring about “the redemption of Ethiopia that now stretches out her hands” before “millennial glory” and declared that the Black freed person “is a son of Adam, and for sin subject to death. He is an object of redeeming love and atoning blood … He is the legitimate object of our prayers, charity and instruction.” Carroll then recommended an evangelistic campaign to send white Southern Baptist pastors and evangelists to “visit and observe” Black Christians “at their places of worship,” distribute religious literature and offer instruction on doctrine, worship and church polity.

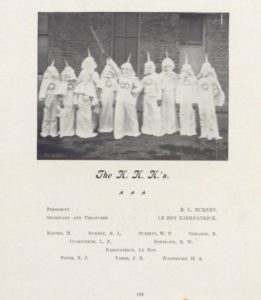

In the Texas A&M University yearbook, 1906, the KKK was a campus organization.

At the end of Reconstruction, Texas Baptist leaders settled on education of Black ministers as the evangelistic plan for the future of segregated churches and increasingly segregated public society. After 1872, as Neches River and other regional associations recognized Black churches in their areas, they began to claim evidence of Black churches and ministers “quitting their old traditions and customs, as well as the grossest of their superstitions. They seem to be more anxious to learn the truth as revealed in God’s infallible Word, and as it is received by their white brethren.”

According to the 1874 Neches River Association report, they observed Black Baptists “maintaining better order in their public worship and using great effort to suppress that boisterousness which has so long characterized their meetings.” Texas Baptists judged the success of their evangelism by how willing Black ministers were to receive instruction by white ministers and whether Black churches reformed their behavior to worship, preach and conduct church polity like white churches.

A history of ‘violent evangelism’

During the Civil War and Reconstruction eras, Texas Southern Baptists sought to continue white authority over the lives of Black men and women after the end of slavery, by means of, to borrow Luis Rivera-Pagán’s term, “a violent evangelism.” They pressed their certainty of God’s divine ordination of the slave master into a theology of gospel proclamation to the slave.

During Reconstruction, they denied the terror happening to Black communities, whitewashed their own history, and recommitted their efforts to spread their gospel proclamation to Black freed persons as a means to ensure white superiority in Texas society.

Z.N. Morrell

The following generation of Texas Baptist leaders lauded their elders for it. In the official denominational history, A History of Texas Baptists (1923), J.B. Cranfill and James M. Carroll printed all the regional and state reports cited above as evidence of Lost Cause mythology about slavery and the Confederacy. J.M. Carroll, a Landmarkist, championed George W. Baines Sr. and F.M. Law’s beliefs in the Southern slave plantation as the most moral order for civilized society and celebrated all signs of Black ministers submitting to white Texas Baptist leaders like Rufus Burleson, second president of Baylor University, and B.H. Carroll, founder of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. Even the Baptist Standard’s J.B. Cranfill, who included an editorial note about G.W. Schobey’s murder, repeated the lie that Black slaves in Texas lived peaceably and defended their masters’ home and family during the Civil War.

Several elements of these historical events provoke lament and mourning. There is so much violence in this history, including the slave master ideology and the evangelistic push for a white gospel. It shakes confidence in the legacy of Southern Baptist mission and evangelism in Texas and beyond.

Many of the Texas Baptists named above also were leaders who built significant Baptist institutions and programs in Texas and among Southern Baptists. But now is the time, as Aaron’s song continued, to “rinse off the whitewash and say the names.” We must reckon with this history, especially those of us who are descendants of Southern Baptist heritage. We must interrogate our gospel theology and cultivate a theology of personhood and redemption that breaks the cycle of reinscribing white plantation patriarchy. Is this gospel of Southern white hierarchy still inside our gospel? Is plantation evangelism still happening today?

As Aaron sings, “This old house won’t be at peace, ’til the front doors open wide and free.”

Laura Levens serves as assistant professor of Christian mission at Baptist Seminary of Kentucky. She is a graduate of Baylor University and earned a doctor of theology degree from Duke University Divinity School. She is ordained within the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and lives in Lexington, Ky., with her husband and two children.

Related articles:

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?

Tearing down statues doesn’t erase history | Opinion by Ella Wall Prichard

When we forget our history, institutions do the sinning for us | Opinon by Greg Jarrell