For decades, progressive white Baptists have opened leadership roles at the highest level to women and people of color. But Black Baptists have shown a greater willingness to affiliate with the conservative Southern Baptist Convention than with more moderate groups like the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. Meanwhile, Southern Baptist women have flocked to hear unapologetically evangelical lay teachers like Beth Moore.

Southern women and Black Baptists stuck with the SBC out of a shared commitment to earnest evangelism, opposition to abortion, support for traditional sexual mores, and an emphasis on the authority of Scripture. Progressive Baptists have talked an inclusive game, but their commitment to evangelism and Scripture seem shaky.

Enter Donald Trump.

The 45th president famously captured 81% of the evangelical vote, and he likely performed at least that well among Southern Baptists. Prominent SBC pastors like Robert Jeffress and Jack Graham scrambled to land a spot on Trump’s evangelical advisory board.

“If 81% of white evangelicals supported Trump, 19% did not.”

But if 81% of white evangelicals supported Trump, 19% did not. It is difficult to find Black evangelicals who support Trump. Even John Perkins, a Black evangelical leader with strong ties to white evangelical churches, was growing more defiant. Toward the end of Trump’s presidency, Perkins stopped talking about “racial reconciliation” because “the phrase implies white and Black people can become equals without addressing historical inequities.” Change was in the wind.

Disaffected Black evangelicals

In 2018, I got a call from a New York Times reporter looking for disaffected Black evangelicals. I took the reporter to visit with Dwight McKissic, a prominent Black Southern Baptist who was openly critical of Trump. The result was “A Quiet Exodus: Why Black Worshippers are Leaving White Evangelical Churches.”

As Kristin Kobes Du Mez observes in a recent Anxious Bench column, Black evangelicals are no longer exiting quietly, and this is particularly true of Black Baptists affiliated with the SBC. Tensions with the SBC leaders attracted national headlines when the presidents of all six SBC seminaries issued a statement denouncing Critical Race Theory. For the past half-century, CRT has provided tools for identifying systemic racism and the subtleties of white privilege. It has denounced the theological defense of slavery and Jim Crow segregation. Remarkably, the seminary presidents, none of whom were well versed in the nuances of CRT, issued their statement without consulting Black pastors and scholars.

Within days, prominent Black megachurch pastors like Charlie Dates and Ralph West announced that they were finished with the SBC. “Their stand against racism rings hollow,” West, a Houston pastor, tweeted, “when in their next breath they reject theories that have been helpful in framing the problem of racism.”

Beth Moore was willing to remain in a pro-Trump denomination until her critique of Trump sparked a wave of denunciation from prominent evangelical preachers. Like the Black Baptists exiting the denomination, Moore discovered that the SBC remained captive to paternalistic racism.

“Progressive Baptists would be thrilled to receive the women and the Black Baptists who no longer feel welcome in the SBC. But it is complicated.”

“I am still a Baptist,” she said, “but I can no longer identify with Southern Baptists. I love so many Southern Baptist people, so many Southern Baptist churches, but I don’t identify with some of the things in our heritage that haven’t remained in the past.”

Progressive Baptists would be thrilled to receive the women and the Black Baptists who no longer feel welcome in the SBC. But it is complicated.

Dueling visions of the church

In 1986, theologian James McClendon predicted that the conservative-moderate divide in the SBC couldn’t be understood until both sides were “brought out and brought under the schooling of the determinative narrative of Jesus Christ.”

Conservatives appealed to the authority of Scripture, McClendon asserted, but their primary concern was the preservation of Southern culture. Self-styled moderates’ appeal to “soul liberty” made theological consensus difficult.

I have spent the past two weeks ploughing through all 977 pages of James Leo Garrett’s Living Stones: The Centennial History of Broadway Baptist Church, Fort Worth, Texas, 1882-1982. Garrett’s writing is tangled and cluttered with extraneous detail, but his thesis is simple: Broadway emerged as a leading congregation within the SBC because it focused on soul-winning and went into a death spiral the moment it abandoned evangelism.

I have spent the past two weeks ploughing through all 977 pages of James Leo Garrett’s Living Stones: The Centennial History of Broadway Baptist Church, Fort Worth, Texas, 1882-1982. Garrett’s writing is tangled and cluttered with extraneous detail, but his thesis is simple: Broadway emerged as a leading congregation within the SBC because it focused on soul-winning and went into a death spiral the moment it abandoned evangelism.

If Broadway had maintained this emphasis, Garrett argued in 1982, she would still be growing. But, for J.P. Allen, John Claypool and Welton Gaddy, the pastors who shaped the congregation’s witness between 1962 and 1982, traditional Southern evangelism had become deeply problematic.

The righteous and the wicked

The heart of that problem lies in Article XVII of the 1833 New Hampshire Confession, which served as Broadway’s first confession of faith. “We believe that there is a radical and essential difference between the righteous and the wicked;” the article declared. Only genuine Christians “are truly righteous” in the eyes of God.” In contrast, “such as continue in impenitence and unbelief are in his sight wicked, and under the curse.”

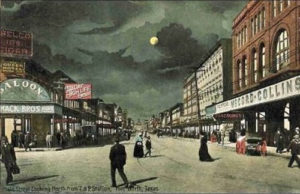

Saloon on Main Street in Fort Worth

Postcard (Source: www.rootsweb.com)

This easy distinction between saints and sinners appealed to a genteel congregation located across the tracks from Fort Worth’s Hell’s Half-Acre, an assortment of saloons, gambling dens and brothels built to service the needs of weary cowboys at the end of a long cattle drive. The notorious red-light district was going strong in 1882 and continued to thrive until the end of World War I.

Gun play and knife fights were a fact of life. But the real victims were prostitutes. Desperate and with nowhere to turn, they took their own lives in shocking numbers. In the eyes of the righteous, these women were wicked and thus God-forsaken.

In 1911, Garrett tells us, Fort Worth pastors launched an investigation of “the Acre,” as it was popularly known. A private investigator “revealed that there were 80 houses of prostitution operating in the zone” and that several of them were owned by “prominent, influential” persons aligned with the very congregations that had paid for the investigation.

Fort Worth’s pastors, including, one assumes, Broadway’s Emmanuel Burroughs, immediately lost interest in their clean-up crusade. But J. Frank Norris, the firebrand pastor of First Baptist Church in Fort Worth, secured the services of the racist and anti-Semitic evangelist Mordecai Ham and launched a 90-day crusade to purify the community. Norris eventually was drummed out of the SBC for his attacks on denominational leaders, but his response to sin established a standard others would emulate.

When Douglas Hudgins accepted Broadway’s call in 1932, he announced that his focus would be on “fighting sin” and “saving souls.” Decades later, Hudgins landed in the pulpit of First Baptist Church of Jackson, Miss., where he served as spiritual shepherd to the leading businessmen, newspaper publishers and Klansmen of Mississippi.

“Hudgins denounced civil rights ‘agitators’ with the same venom J. Frank Norris had aimed at Hell’s Half Acre.”

When Freedom Riders were arrested on the streets of Jackson and hauled off to the notorious Parchman prison, Hudgins applauded. In his book on “Freedom Summer,” theologian Charles Marsh called Hudgins the “premier theologian of the closed society.” Hudgins denounced civil rights “agitators” with the same venom J. Frank Norris had aimed at Hell’s Half Acre. A segregated Mississippi, Hudgins declared, was “ordained by God as part of his design for the created order.”

Hudgins had it exactly backward. In the social drama playing out in 1960s Jackson, the righteous were being hauled off to prison and the wicked were sitting comfortably in the pews of First Baptist Church.

A new take on an old gospel

Back in Fort Worth, when Guy Moore passed the pastoral torch to Jimmy Allen in 1962, Broadway was exposed to a new take on an old gospel. A new generation of Southern Baptist scholar-pastors had been exposed to Ivy League culture, the neo-orthodox theology of Karl Barth and Reinhold Niebuhr, a surging ecumenical movement, and the non-violent direct action of Martin Luther King Jr.

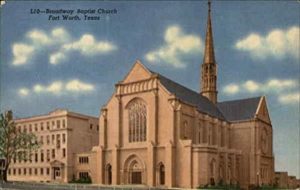

Vintage postcard of Broadway Baptist Church

J.P. Allen wasn’t sure how to blend these exciting new trends with the Southern piety of his youth, but he was determined to make the pieces fit. Broadway’s facilities now were surrounded by poor neighborhoods and intractable social problems. Under Allen’s leadership, the congregation responded vigorously to the need.

John Claypool introduced Broadway to confessional preaching. He didn’t have all the answers and repeatedly said so. He shifted the focus from evangelical proclamation to liturgical mystery, a tradition Welton Gaddy, Claypool’s successor, embraced with enthusiasm.

The viability of institutional life

These developments made James Leo Garrett uneasy. In Living Stones, he argued that Broadway’s focus had “shifted from evangelism, visitation, participative church training, Sunday school enlargement, and mission-and-church-planting” to “more liturgical worship, more emphasis on Holy Week and Advent, pastoral care and nurture of its members, and a Christian social ministry to persons and families in the community having specific needs.”

Garrett was a Broadway deacon and a theology professor at Fort Worth’s Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary when he churned out Living Stones. With a Harvard doctorate, Garrett was familiar with the theological currents of the time. He endorsed the Civil Rights Movement. He favored ecumenical dialogue. But his overriding commitment was to the continued viability of SBC institutional life. And that, as everyone realized in 1983, was in jeopardy.

As Broadway sought new ways of living and preaching the Christian gospel, an informal network of like-minded churches evolved across the South. Cecil Sherman, the plain-spoken preacher who took the helm at Broadway in 1985, identified two large groups within Southern Baptist culture.

“There was a group that was into evangelism … and there was a group clustered around missions and the denomination.”

“There was a group that was into evangelism,” Sherman wrote in 2007, “and this group tended to be conservative theologically. And there was a group clustered around missions and the denomination” and came down on the progressive side of issues like race, hunger, ecology and the role of women in church and society. These two groups were almost exclusive. If you were in one, you were not in the other. I never invited one of the rightwing to my church. Their gospel was different from mine.”

Today, a reckoning

As McClendon predicted 35 years ago, both kinds of Baptists are now facing a stern reckoning. Eager to overcome its association with human bondage and Jim Crow injustice, the SBC has attempted to stir a little racial reconciliation into the denomination mix. But the rise of Donald Trump has exposed the inadequacy of these efforts.

Meanwhile, comparatively progressive Baptist churches like Broadway have struggled to find a way forward. When Broadway ordained its first female deacons in 1981, six male deacons resigned in protest and a few families drifted from the fold. In 2008, gay couples asked to appear together in the church’s pictorial directory and the congregation fractured.

Now, we are confronting the systemic roots of poverty and racial injustice. Mere charity, we realize, is insufficient. We can’t find solutions until we admit that we are a much larger part of the problem than we had imagined.

Our fixation with the line between the righteous and the wicked has deflected our attention from what McClendon called “the determinative narrative of Jesus Christ.” Pogo had it right: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

If a congregation has been steaming full-speed in the wrong direction, the wise move is to cut the engines until the ship can safely make a wide U-turn. There are no shortcuts. No easy answers. No simple formulas. But we’re heading in the right direction. We can feel it. And after generations of uncertainty and turmoil, that comes as a tremendous relief.

Alan Bean

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas, and is a member of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth.

Related articles:

James Leo Garrett, theologian who influenced two generations of Baptist scholars, dead at 94

SBC targets Texas church over homosexuality

Jimmy Allen, visionary denominational leader, dies

Remembering John Claypool on the 10th anniversary of his death