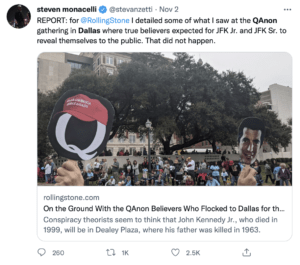

All things considered, an event in Dallas on Nov. 2, 2021, had the makings of a post-Christian kingdom of God moment for the subgroup of QAnon believers gathered in Dealey Plaza, site of the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy on Nov. 22, 1963.

Numbered in the “hundreds” in a Washington Post report, they awaited the return of the slain president’s son, JFK Jr., himself killed in a plane crash in 1999, but whom they believed to be in hiding for the last 22 years. For these QAnon devotees, Kennedy’s return would create a cathartic moment in America when Donald J. Trump, reinstated as president, would name JFK Jr. as his unelected vice president. The younger Kennedy would ultimately succeed Trump, who would then become, in the words of one QAnon “influencer,” “one of seven new kings. Most likely the King of Kings.”

But JFK Jr. did not appear on Nov. 2, and the crowd of believers dispersed, but not before some in their number speculated that Kennedy would instead show up that very night at — wait for it — a Rolling Stones concert in Dallas. From first century Christianity to 21st century QAnon, apocalyptic disappointments require considerable renegotiation.

But JFK Jr. did not appear on Nov. 2, and the crowd of believers dispersed, but not before some in their number speculated that Kennedy would instead show up that very night at — wait for it — a Rolling Stones concert in Dallas. From first century Christianity to 21st century QAnon, apocalyptic disappointments require considerable renegotiation.

Before we say, “You can’t make this stuff up,” we’d best remember that somebody actually did. Don’t laugh. OK, chuckle a little if you must, but don’t dismiss this event (or me for writing about it) too readily. What if the Dealey debacle is yet another “sign of the times,” a fanciful yet sobering illustration of what happens in a culture shredded by conspiracy theories, “alternative facts,” “Big Lies,” and, sadly, bastardized theology? (I’m speaking theologically here.)

Consider the implicit and explicit elements of dogma and definition that connect the “second coming of JFK Jr.” to assorted facets of Christian belief and praxis:

- An eschatological moment that ushers in a new era of socio-political redemption, thus achieving the overarching QAnon goal by which Trump oversees the arrest, trials and death sentences of a perceived “elite global cabal of Satanic pedophiles” promulgating large-scale child sex trafficking.

- An implicit resurrection narrative in the return of Kennedy Jr. to American life and national leadership.

- The elevation of Trump from the presidency to “king of kings,” an office that unites him with the biblical king Cyrus, a comparative casuistry promoted by assorted evangelical leaders who suggest that while Trump, like Cyrus, was morally compromised, both were authoritative protectors of “God’s people.”

- In this way, the QAnon faithful in Dealey Plaza sought to co-opt aspects of Christian theology for their own post-Christian socio-political agendas.

Not everyone in the QAnon movement concurred with their utopian vision. The Trumpian “king of kings” label was clearly a bridge too far for certain representatives of QAnon “orthodoxy.” Movement leader John Sabal declared: “There is only one king of kings, and that is our Lord and Savior Yeshua/ Jesus Christ. This (title for Trump) couldn’t be more wrong,” an affirmation of faith uniting the Q and Jesus stories.

Other QAnon critics blasted “orthodox” and “heretical” QAnon constituencies alike. The Anti-Defamation League equates QAnon with earlier Christian anti-Semitic accusations and practices, insisting, “The belief that a global ‘cabal’ is involved in rituals of child sacrifice has its roots in the antisemitic trope of blood libel, the theory that Jews murder Christian children for ritualistic purposes.”

Other QAnon critics blasted “orthodox” and “heretical” QAnon constituencies alike. The Anti-Defamation League equates QAnon with earlier Christian anti-Semitic accusations and practices, insisting, “The belief that a global ‘cabal’ is involved in rituals of child sacrifice has its roots in the antisemitic trope of blood libel, the theory that Jews murder Christian children for ritualistic purposes.”

As QAnon gained adherents within Christian congregations, courageous evangelical pastors responded, warning their parishioners to resist engagement with the “conspiracy cult.” A May 23, 2021, story from CNN Business focused on the efforts of two pastors, one in California, another in North Carolina, who alerted their congregations to the dangers of the movement, opposing those who assert that QAnon and Christianity might “run on parallel tracks.” The story documents a recent survey by the conservative American Enterprise Institute in which some 27% of evangelicals affirmed that Trump’s alleged secret battle against an elite group of child sex traffickers is “mostly or completely accurate.”

In his critique of QAnon, James Kendall, the California pastor, acknowledges that while evangelical Christians await Christ’s return to “judge the wicked” and redeem the faithful, the advocates of QAnon insist that, “Donald Trump is going to come back and judge the wicked, set up his rule, and his followers are going to live in their little utopia.” Given those similarities, Kendall admits, “It’s easier for Christians who already have that belief system to make that jump over into believing (QAnon).”

What’s causing all this? On one hand, “strange new religions” are nothing new in America, evidenced in apocalyptic movements such as the Shakers and Oneida communities, Mormonism, Heaven’s Gate, and Jonestown. Yet QAnon in general and the Dealey Plaza event in particular reflect a unique configuration of conspiracy theories, New Age utopianism, Trumpian authoritarianism and JFK tragedy, with Christian millenarianism.

“It’s easier for Christians who already have that belief system to make that jump over into believing (QAnon).”

Surely the QAnon phenomenon is further evidence of the multiple tensions within the American body politic, Protestant/Catholic establishments, and a ceaseless culture war on multiple fronts. From an ecclesiastical perspective, perhaps it is important to acknowledge ways in which American Christianity may knowingly and unknowingly, explicitly and implicitly, facilitate, complicate or contribute to cultic movements bound by conspiracy theories and apocalyptic obsessions. These theories and obsessions may be shaped by:

- Christianity-based millennial and numerological speculation.

- Fundamentalist-oriented dogmatism demanding doctrinal uniformity.

- Populist reinterpretations of traditional Christian beliefs and practices.

- Disintegration of effective methodology and theology of Christian evangelism.

- Rabid individualism that resists “mandates” whether social, communal, governmental or theological.

- Dramatic increases in religious “non-affiliation” and “disengagement” from faith communities.

- Rampant conspiracy mythologies, often with little or no basis in fact.

Realizing that these are merely symptoms, I searched for a diagnosis and found it in a 1957 essay by the Romanian/French playwright Eugène Ionesco (1909-1994). Describing his play The Chairs, Ionesco wrote: “I have tried to deal more directly with the themes that obsess me; with emptiness, with frustration, with this world, at once fleeting and crushing, with despair and death. The characters I have used are not fully conscious of their spiritual rootlessness, but they feel it instinctively and emotionally. They feel ‘lost’ in the world, something is missing which they cannot, to their grief, supply.”

Ionesco’s words read like a commentary on our fragmented American Republic, tragic signs of our 2021 collective identity crisis that stretch from Jan. 6 in Washington, D.C., to Dallas’ Dealey Plaza, Nov. 2, events that profoundly reflect American “emptiness,” “frustration” and “spiritual rootlessness.”

If Christ’s gospel can’t bind up at least some of that collective brokenness, then we’re still a long, long way from home.

Bill Leonard

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

New PRRI study builds a profile of QAnon believers

Is QAnon a prophet or provocateur? And how should Christians respond?

‘How can I talk to my parent who has been consumed by Trumpism and QAnon?’