If you want to understand the gender and sexual anxieties of evangelical Christians today, look at the seeds sown in their midst in the 1970s and ’80s, according to a couple of researchers recently posting on the topic.

Marlena Graves is a Ph.D. student in American culture studies at Bowling Green State University, where she is researching the influence American culture has on evangelicals’ view of immigration, race, and poverty. She recently posted on Twitter a news clip from 1980 where the Moral Majority opposed the Domestic Violence Prevention and Services Act.

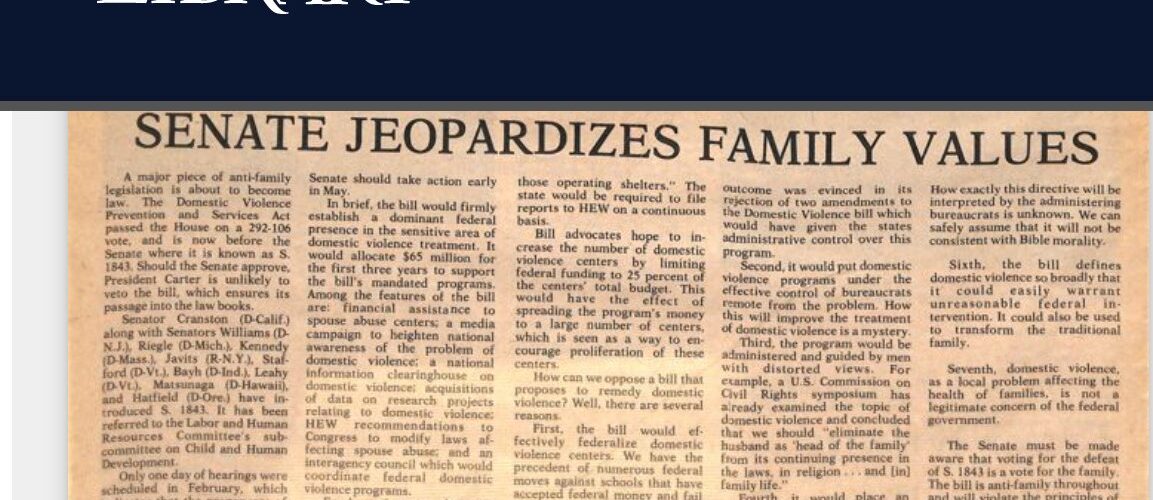

The headline in the Moral Majority newspaper reads “Senate Jeopardizes Family Values.” The article describes the Congressional effort to prevent domestic violence as “anti-family legislation.”

At the time, the landmark legislation had passed the House and was up for a vote in the Senate. President Jimmy Carter was assured to sign it once it passed the Senate, which put the Moral Majority in a panic.

In an echo of Christian support for segregation, the Moral Majority lamented that this bill would “federalize domestic violence centers” and take away state authority.

Why would an organization claiming Christian moral values oppose legislation to prevent domestic violence and help victims? The Moral Majority gave seven reasons:

- States’ rights. In an echo of Christian support for segregation, the Moral Majority lamented that this bill would “federalize domestic violence centers” and take away state authority.

- Putting “bureaucrats” in charge of a problem they have no business with.

- The effort would be “guided by men with distorted views.” The article gave specific reference to those who would “eliminate the husband as head of the family.”

- It would “place an undue emphasis on separation as a solution to domestic violence. This would violate a fundamental moral precept and represent a victory for humanism.” For decades, evangelical leaders have been criticized for counseling abused women to remain in abusive marriages.

- The bill would not likely be “consistent with biblical morality.”

- The bill is “so broad” that it could lead to “unreasonable federal intervention” that would “transform the traditional family.”

- “Domestic violence, as a local problem affecting the health of families, is not a legitimate concern of the federal government.”

Sarah Stankorb is a freelance religion writer who is a graduate of the University of Chicago’s Divinity School. She recently wrote an article on Medium about her current research into the influence of James Dobson and Bill Gothard on evangelical views of gender and sex. The piece is titled “Retrograde Biblical Interpretations of Womanhood and Parenting Are Still Here.”

In the online article, she highlights actual pages from training materials published for evangelical Christians in the 1970s and ’80s.

“I’ve spent the past couple of weeks reading through a variety of books that once carried great influence within evangelical Christian households and for some, still do,” she wrote. “These books insisted the godly path in parenting meant a particular type of discipline: corporal punishment with a switch or a belt (per James Dobson’s The Strong-Willed Child). Women were warned to dress modestly with specific haircut recommendations according to face shape. Women were also tasked with protecting men from sexual temptation by wearing scarves and short jewelry to keep men’s eyes up at their faces — no long strings of beads or dangling earrings that create “eye traps” below the neckline (see Bill Gothard’s Advanced Seminar Textbook).”

Among the examples she found was advice from Gothard’s 1983 “Men’s Manual” from a “Financial Freedom” seminar. Gothard, who never marrid and later was accused of recurring abusive behavior toward women, advised that women should not work outside the home. And he warned that if “a woman goes off to work, in anticipating the needs of her (assumed to be male) boss, she could develop greater admiration for her boss than her husband,” Stankorb summarized.

Among the examples she found was advice from Gothard’s 1983 “Men’s Manual” from a “Financial Freedom” seminar. Gothard, who never marrid and later was accused of recurring abusive behavior toward women, advised that women should not work outside the home. And he warned that if “a woman goes off to work, in anticipating the needs of her (assumed to be male) boss, she could develop greater admiration for her boss than her husband,” Stankorb summarized.

Gothard also advised that it was more economical for a family if the woman stayed home with children because of the increased costs of child care and grooming and wardrobe that working women would incur.

Stankorb commented: “Setting aside the failure to recognize a woman might find personal fulfillment at work, which is not factored into this funny math, there’s also a degree to which this narrative rings true for many families thanks to policy decisions based in the same culture war Gothard and Dobson were engaged in.”

And she draws a line from these 20th century evangelical leaders to today’s debates around the economic realities of COVID: “Today, the pandemic’s child care crisis has laid bare how much women’s workforce participation is still dependent upon stable child care (with a lasting impact on the gender wage gap and productivity overall). Gothard’s calculations, to me, demonstrate less how costly a woman working, with her lunches and increased tithing might be, but rather how a broken child care system has been weaponized against working women for generations.”

Stankorb has dug into this bit of evangelical history as preparation for a writing project. But she said the research has reminded her that the influence of these male-dominant ideologies lives on today.

“I’ve heard from too many women still scarred by family members who claimed they were harming their children by choosing to work — even when finances demanded they must.”

“For those of us a step removed from such ‘teachings,’ their leaps in logic can be almost laughable,” she wrote. “Except, for too many people Dobson, Gothard, et al., held authority over major stretches of their lives. I’ve heard from too many women still scarred by family members who claimed they were harming their children by choosing to work — even when finances demanded they must. Too many describe following these rules for motherhood, devoting all their energy and resources through the most productive years of their lives to their families, not because they wanted to but because their church or these teachings convinced them it’s what God demanded of them. Then one day, the kids grow up; she’s poured herself away and feels like she’s starting from nothing.”

Ultimately, these warped views have empowered domestic violence under the guise of biblical family values, she asserted, citing a Dobson story about exerting his authority over his dachshund with a “small belt” as a teaching about how to handle strong-willed children.

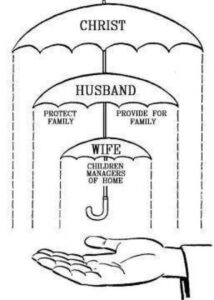

“I’ve lost track of how many people have described this story’s influence over their own family’s choices in discipline and punishment, children treated as one ought not treat a dog,” she wrote. “If, as girls, they were taught to submit no matter what to their father, in preparation for submitting to their husband, it was because their family truly believed in Gothard’s ‘umbrella of protection.’”

That unique teaching, featured in Gothard’s Institute in Basic Youth Conflicts seminars, originally was illustrated by the husband as a hammer striking the wife as a chisel, who in turn shaped the children as stone. It later was updated to show a series of umbrellas, with “Christ” as the overarching umbrella covering the husband as the next-largest umbrella, which in turn covers the wife as a smaller umbrella, under which the family and children reside safely.

That unique teaching, featured in Gothard’s Institute in Basic Youth Conflicts seminars, originally was illustrated by the husband as a hammer striking the wife as a chisel, who in turn shaped the children as stone. It later was updated to show a series of umbrellas, with “Christ” as the overarching umbrella covering the husband as the next-largest umbrella, which in turn covers the wife as a smaller umbrella, under which the family and children reside safely.

While not everyone influenced by this teaching turned out to be abusive, there is a direct line between this theology and a sanction to abuse, Stankorb wrote.

“Yesterday, as I read court documents from an old church sex abuse case, I felt vomit rising in my throat. Over the years, I’ve heard some truly catastrophic stories and to some degree, I can find a place within myself to focus on the process of information gathering, the collection and checking of facts, staying stoic for a source so they have the space to convey what they need to. But on the heels of reading book after book that was each so popular and convinced millions of women and children to place full faith in a father, and in turn in a male pastor, reading count after count of abuse made my stomach churn.

“In this case, the abuse was known — sometimes allegedly perpetrated by pastors themselves, another time, a father known well by pastors — and those pastors were trusted to deal with the abuse. They didn’t report to the police. They tried to keep families from doing so. They invested church funds in defending the abusers. They manipulated the deep trust the churches had in them and exerted authority over their congregations.

“And one after another, children were hurt in the most vile ways I’ve ever encountered.”

Related articles:

I survived the Christian fundamentalist world that created Josh Duggar | Opinion by Lydia Joy Launderville

The weakness of complementarian theology on display in Duggar trial | Opinion by Rick Pidcock

Lawsuit accuses once-admired evangelical family expert of sexual abuse

White evangelical leaders who repress women are revered as saints, author says

SBC Executive Committee publicly apologizes to sexual abuse survivor