You and I see it almost daily: A person doesn’t know when to let go of their position of power. A father or mother, high executive or low manager, a lay or professional leader, a bus driver or bus mechanic. We’ve seen this behavior — holding on for too long.

This is difficult discernment, realizing, as Kenny Rogers lamented, you’ve got to “know when to hold ’em and when to fold ’em.”

I’m assuming we, writer and reader, share a love for and commitment to the church. The dilemma I’m raising occurs in any system, but let’s focus on an experience we share.

You will recognize these examples:

- “She was very effective, well-loved and appreciated. She just stayed too long in the position.”

- “In the congregational meeting he seemed so desperate, so out of character. Since he resigned as chair of the committee, he’s not the same. What’s going on with him?”

- “Since leaving her position, I don’t think it’s right for her to keep calling committee members expressing her opinions.”

- “It’s sad. He won’t even talk with us about retiring.”

You could think of other samples.

You know this behavior. You see it in others; you see it in yourself. Either way, you condemn it, as do I.

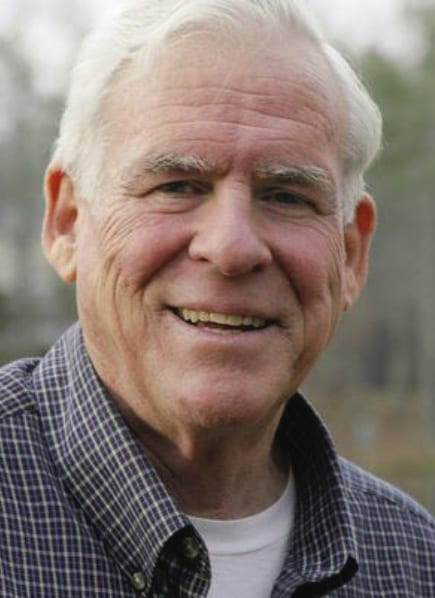

Mahan Siler

I’m proposing an alternative to condemnation.

The issue is power. Or, if you prefer, we could speak of power as influence or agency. You and I want to possess and express agency. We want to have influence. We want to make a difference in this world. We desire to live empowered lives. These positions — roles like parent, chairperson, teacher, director, organist, pastor, writer, administer — grant us agency. These positions, usually well defined, are portals through which we can contribute. They enable self-giving.

I’m naming this agency as positional power.

If the issue is power, then powerlessness may be one of our deepest fears. This feeling is ambiguous. On one hand, confessing our powerlessness to control an addiction is the first step toward freedom from surrendering to a higher power.

“The loss of influence can feel like the loss of self.”

On the other hand, we can interpret powerlessness as the loss of agency. The loss of influence can feel like the loss of self. We wonder, who am I apart from this identity? How disorienting it can be when our position, like a rug, is pulled out beneath us. Where and how will I contribute and make a difference?

I’m appealing for understanding of those who lose their place of contributing. No wonder we often cling to positions of power. For good reason we resist letting go of roles that provide grounding to our ways of serving. Who wants to forfeit their ways to influence? We want to matter.

I’m proposing an option that respectfully maintains our human need for empowered agency in the world. Consider the movement from positional power to relational power.

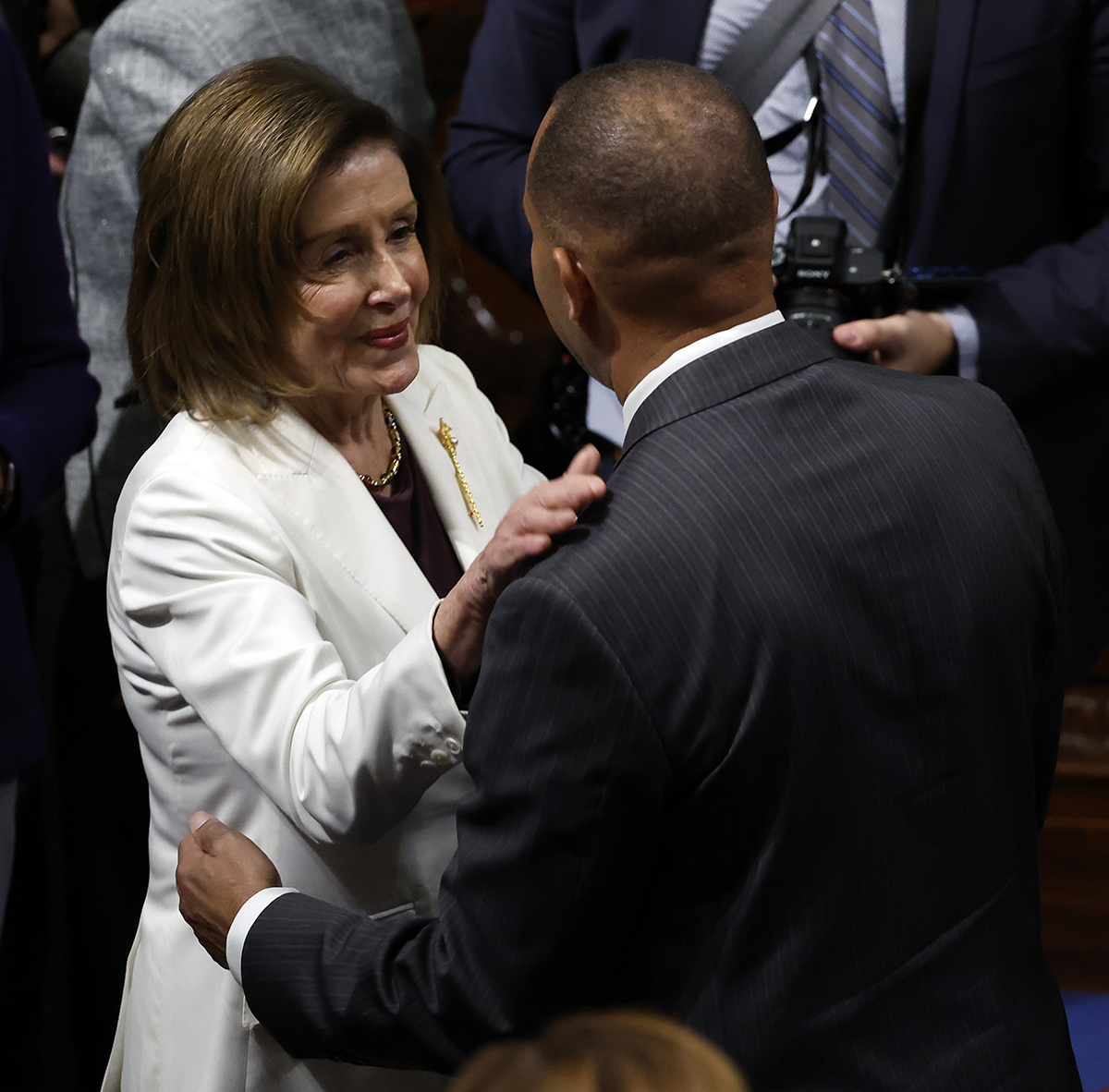

Whatever you may think of her political leadership, Nancy Pelosi offers a perfect example of this shift in power. On Nov. 17, 2022, she came before the camera announcing her resignation as speaker of the House of Representatives. She is ending her nearly 20-year history-making tenure as the first woman to serve as speaker. Now age 82, it’s time.

Most public leaders resign, leave their post and go home as “thoroughbreds put out to pasture,” we might say. Some write memoirs to mark their “race” in time. For them it’s clear, they are leaving the playing field, saying “goodbye” to their time of public service. That’s the usual script of public figures leaving office.

Former U.S. Speaker of the Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) talks to then House Democratic Conference Chairman Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) after Pelosi said she would not seek a leadership role in the new Congress, paving the way for him to succeed her. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

Not so with Nancy Pelosi. She resigned as speaker but remained as a House member still representing the city of San Francisco. Why would she resign as leader of the Democratic caucus and still be a member? Why would she forfeit such power as speaker for a less-powerful position? She spoke of stepping down as the upfront leader in order to support younger members assuming new positions of leadership.

When I heard her announcement, I said to myself, “There it is!” She is moving from positional power to relational power. She is making accessible to younger leaders her network of relationships. No longer in the position of leader, she is stewarding her power within relationships formed over time.

In 1983, I was called to become pastor of Pullen Memorial Baptist Church in Raleigh, N.C. On my first day, I met with Bill Finlator, my predecessor. I felt honored to follow such a prophetic presence and voice during the 1960’s and ’70s.

I began a conversation appropriate for transitions.

“Bill, you have had a remarkable ministry with Pullen for 26 years. People will want you to share in the leadership of funerals, and I hope you will be open to these requests when they come.”

Bill quickly inserted, “Mahan, I will be your friend but don’t ask me to do one thing for Pullen Church!”

My mouth dropped from amazement. His hurt was deep, so much so it took 10 years before he was willing to preach and reconnect with Pullen. Thankfully, healing occurred and years later there was a grand celebration of his life at Pullen.

As he promised, in spite of his grief, he befriended me. He couldn’t have been more supportive. During my 15-year tenure, Bill and I enjoyed a close friendship. When I announced my retirement, during a lunch meal, he said: “Mahan, I wish I had ended differently. I was too stubborn. I wouldn’t talk with anyone about my retirement. I stayed too long.”

I remember my response. “Bill, you have been a pastor all your adult life. I haven’t. I know there is life beyond this role. I suspect you felt like your influential ministry was finished when you left Pullen.”

I reference this story as an illustration of this shift of power or lack of it. Bill discovered a different kind of power. His aging during post-retirement years was filled with opportunities that accessed his experience. Free from some of the confinement of his position as pastor of a congregation, he activated his vast network of relationships who shared his passion for social justice.

I offer this frame to those of us who face the end of roles that have been for us positions of influence. Or we may be observing this dilemma in someone else. Given our human need for agency, the exploration of relational power may be welcome news.

The choice is not power or no power. It’s appreciating both positional power and relational power.

Mahan Siler lives in Asheville, N.C. He is a graduate of Vanderbilt University and Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He was one of the founders of the Alliance of Baptists and served two congregations as pastor, Ravensworth Baptist Church in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., and Pullen Memorial Baptist Church in Raleigh, N.C. He also has worked in pastoral care in the health care setting.