Sometimes art tells a heartwrenching story better than words.

Perhaps the greatest example of this is found in the three broad categories of Christian art depicting the sorrows of Mary after the death of Jesus: Pietá (pity; Italian), Mater Dolorosa (Our Lady of Sorrows; Latin), and Stabat Mater (The Mother Was Standing; Latin).

The most famous of these pieces is Michelangelo’s Pietá, a sculpture that sits in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome behind a bullet-proof glass panel.

Michaelangelog’s “Pieta.”

Michelangelo shows Mary loosely holding the limp body of Christ in her lap. Her head is pointed down toward her son, but her eyes are closed and her face is solemn. The body of Jesus is contorted so that viewers of the statue cannot easily see his face, as his limp neck allows his head to fall back behind his mother’s arm.

One of Mary’s hands peeks out by Jesus’ right arm, holding his body somewhat upright. Her left hand is placed with its palm facing the sky, indicating that she may be praying.

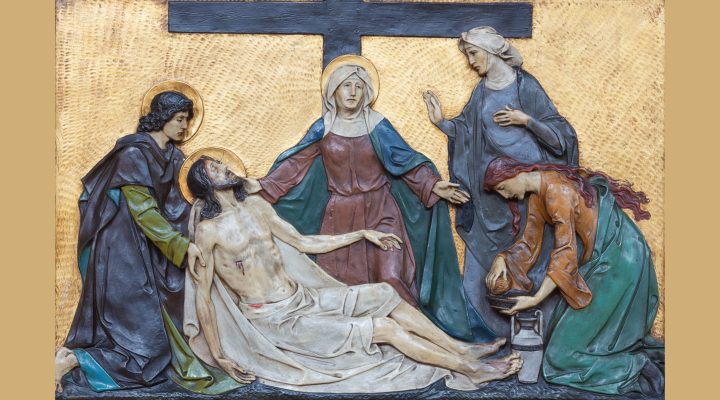

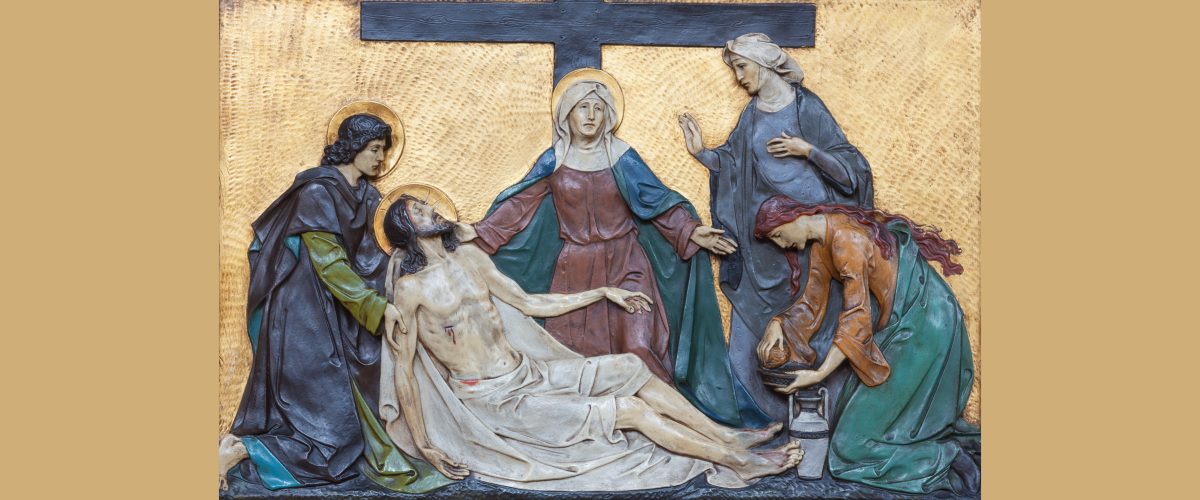

Other pieces in the Pietá category also depict the body of Jesus laying limp, often over the top of the lap or body of his mother, and sometimes other figures such as Nicodemus, Joseph of Arimathea or Mary Magdalene.

Seven Swords Piercing the Sorrowful Heart of Mary in the Church of the Holy Cross, Salamanca, Spain.

Pieces in the Mater Dolorosa category typically depict Mary more emotionally, often with swords piercing her chest, or looking downward in sorrow. At times, she may also be depicted alongside other events that occurred during the Passion narrative.

These pieces depict how the events of the passion narrative metaphorically pierced Mary’s heart, causing her to mourn with great pain and suffering.

The final category of artworks, Stabat Mater, depicts Mary standing at the foot of the cross as Jesus is crucified, often alongside John the apostle.

The “Deposizione,” mid-15th century, by Napolitan Colantonio (Naples, Museo di Capodimonte).

Typically, these pieces show the mother looking uncomfortable or sorrowful. She often has her hands folded as if she is praying or laid out with her palms upward. Some artists depict her as looking up at Jesus as he suffers, while others depict her looking at the ground or with her face burrowed into her hands. On the cross, Jesus is typically bleeding, indicating that his life has ended.

These pieces, especially the Pietás, famously attract viewers because of their depictions of Christ’s suffering. The vulnerability of Jesus as his body is weakened is quite relatable to us — there is great power in seeing our God taking on such a natural, and human, state.

However, the artistic focal points of these pieces depict something profound: the suffering and strength of a mother as she cradles the body of her dead son.

“The artistic focal points of these pieces depict something profound: the suffering and strength of a mother as she cradles the body of her dead son.”

We often look to the passion narrative as an expression of Christ’s strength; he has made a powerful sacrifice that should be celebrated. But for Mary, this was a moment of sorrow. Her child has died, and she must now grieve.

These depictions of Mary epitomize the suffering she has faced her entire life.

At Jesus’s conception, Mary faced social discrimination as an outcast by being pregnant before marriage. She gave birth to him in a barn with animals and dirt, forced to go through birthing pains in improper (and probably uncomfortable) conditions. Due to the scandal of his existence, she was forced to become a refugee to avoid the infanticide of her newborn son. Throughout his ministry, she had to look upon him while he was hated by those in power.

And now, at the moment of his death, she must once again bear the burden of mothering such an important son. She must witness his pain and watch his holy body succumb to a death reserved for criminals. as the suffering and death of her beloved incite joy and salvation in the hearts of others.

“At the very climax of the Christian narrative, Jesus is held together by his mother’s strength.”

And yet, in this moment of grieving, Mary holds the body of her son, facing the swords that pierce her heart, or standing bravely at the foot of the cross for everyone to see. At the very climax of the Christian narrative, Jesus is held together by his mother’s strength.

The strength to hold his limp body over her lap. The strength to face social persecution from those who hated her son. The strength to live without him on the earth. The strength to mourn publicly for a man accused of blasphemy against her own God.

One may not think to categorize mourning and strength together in this way, but this is the reality Mary faces in this scene.

Her tender love for Jesus is not only the love of a believer for her God, as many of us feel for Jesus. It is simultaneously a love of faith and a love of maternity. Jesus, despite his status as God, needed the strength and tenderness of his mother to make his sacrifice complete.

Mothers everywhere know how Mary feels, to an extent.

They would do anything for their children, even if they had to suffer terribly just to offer their bodies an embrace. Maternal love is vital to the life and death narrative of Christ, and it is because of Mary’s mournful strength that we can celebrate the cross with such ferocity today.

Mallory Challis is a senior at Wingate University and serves this semester as BNG’s Clemons Fellow.

Related articles:

These contemporary icons show the saints among us in a new light

Q&A with Daniel Bonnell on conveying the sacred in modern art

Study asks how art influences faith

A pastoral dilemma about art and nudity: embodied faith and raising children in the church | Opinion by Mark Wingfield