Last weekend I was fortunate to attend a stop on “The Stories God Tells” tour featuring Jonathan Merritt (award-winning columnist at The Atlantic, and now children’s book author) and Matthew Paul Turner (New York Times bestselling author of several beloved children’s books).

This stop at Royal Lane Baptist Church in Dallas also featured the church’s senior pastor, Victoria Robb Powers, who recently co-authored a children’s book, and Joanna Carillo, who illustrated both Robb’s and Merritt’s books.

Merritt’s opening remarks speak to the importance that the stories we tell hold:

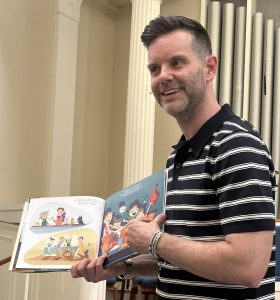

Jonathan Merritt reads from “My Guncle and Me.” (BNG photo by Mara Bim)

The stories we choose to tell matter more than most people realize. Especially when the people we’re telling those stories to are our children. Herein lies the problem. You see, the stories we humans often tell are not very good stories. They’re stories of disempowered females. Or males solving problems with violence. They’re stories of love that looks a lot like codependency. They’re stories that stir in our hearts anger toward others or shame about ourselves or fear about something or someone that we’ve been told is a threat. The reason that we’re here tonight is because we believe that these are not the stories that God tells. We believe that a good God tells good stories. That a loving God tells loving stories. That the liberating God tells liberating stories. And these are the stories that the people that you will hear from tonight are committed to telling.

Turner, Merritt’s counterpart on the tour, is undoubtedly familiar to anyone who attends a Mainline Protestant church and has a child under the age of 10. Ten years ago, Turner stepped into what was then a void in the world of Christian children’s books. Everything else on the market was written for parents within the Bible-thumping, evangelical church traditions and was dominated by patronizing, moralistic stories intended to churn out “good children.” Turner offered something new for those of us parenting outside of church contexts that demand literal, legalistic and toxic interpretations of the Bible.

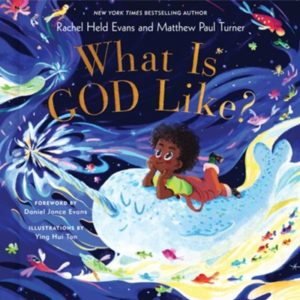

I first became aware of Turner with the 2021 release of his book written with the late Rachel Held Evans. My daughter had just turned 5, and after reading their book What Is God Like? I went out and bought every single one of his children’s books because they so poignantly capture what I want my daughter to know about God, herself and others: That God is love and everyone who loves knows God (1 John 4:7).

Which is why this book tour and the message it brings is so very important both for children and for the grown-ups among us. Merritt emphasized this point to the mostly adult audience gathered: “One of the reasons why we make kids’ books for kids is to teach them things we hope they’ll never forget. One of the benefits of adults reading children’s books is to remind ourselves of the things that we’ve forgotten.”

Matthew Paul Turner reads from one of his children’s books. (BNG photo by Mara Bim)

Storytelling is sacred work. Storytellers have been among every people group that ever has lived on this little planet we call home. Storytelling about God and God’s relationship with humankind is especially sacred.

Powers spoke of the responsibility churches have in the narratives they promote about God:

The stories we tell about God shape the way we see ourselves, the way we see others and the way we see the world. … Religious trauma often comes as a direct result of telling false and harmful stories about God. Stories that lead people toward stress and shame and sometimes even self-hatred. … The stories we tell about God have a really unique kind of power. They have the power to heal or they have the power to harm. Most of the stories we tell about God we get from the Bible, but we have choices. We have choices about how we interpret these stories and how we tell these stories.

Which brings me to the children’s books around which this tour is centered.

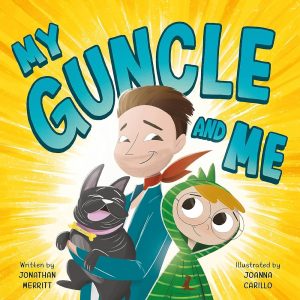

Merritt’s book, My Guncle and Me, tells the story of Henry, a little boy who struggles with being different, and of the love and compassion shown to him by his guncle (shorthand for a gay uncle). “When I get really sad, my guncle squeezes my hands. He lets me cry all my tears, and says he understands,” the books says.

During his visit, Guncle joins Henry and his family at church, and for anyone who has experienced the viciousness of a self-righteous congregation, this part of the story rings especially true.

At church the next morning, my guncle sings loudly. He prays and gives thanks, and he does so devoutly. His bright-colored outfit makes two women stare. When we pass, they both snicker, but he doesn’t care.

After Guncle leaves, Henry remembers his parting words, “You’re the most special child that I’ve ever known. So keep being yourself even when you are grown.” Henry takes the words to heart and blossoms at school, learning to love himself and others. For, as we all know but too often forget, “in order to love other people that way, you must first love yourself and know you’re OK.”

After Guncle leaves, Henry remembers his parting words, “You’re the most special child that I’ve ever known. So keep being yourself even when you are grown.” Henry takes the words to heart and blossoms at school, learning to love himself and others. For, as we all know but too often forget, “in order to love other people that way, you must first love yourself and know you’re OK.”

Similarly, Turner’s new book, You Will Always Belong, affirms to young readers that they are beloved and that they belong — they belong to God, to their families, friends and communities and, most importantly, they belong to themselves.

On your very first day, when you breathed on your own, you belonged to yourself and were made to be known. … ’Cause all that God saw when God designed you was beauty and purpose and everything true.

The book concludes with the beautiful and hopeful message, “When you celebrate you, God celebrates you too, and the world becomes brighter and a little bit new.”

What might our world look like if the stories we all told about God were ones like these of love, joy, peace, kindness and hope?

Joanna Carillo (BNG photo by Mara Bim)

In discussing her work, Joanna Carillo referenced a metaphor she uses in illustrating children’s books — a metaphor one of my Old Testament seminary professors used when talking about how we are to read and interpret Scripture. Carillo explained how she uses the metaphor of “mirrors and windows” in her illustrations: “You can either look through a window and see someone else’s life or someone who’s similar to you/different from you — worlds that could be possible. Or, a mirror. You see yourself.”

The same is true of biblical texts. When someone sees only a dominating, jealous God in the text, it’s worth asking the question whether one is looking through a window or into a mirror.

Carillo illustrated Merritt’s My Guncle and Me as well as the book Powers co-wrote with Cameron Mason Vickrey, My Love, God is Everywhere, which has become a favorite of both me and my now-8-year-old daughter.

Throughout My Love, God is Everywhere, a little girl asks her mother where she can find God in everyday life, and her mother lovingly affirms that God is always with us. God is found higher than the trees and lower than things beneath the dew. God is present when life is loud and chaotic just as God is present in stillness and quiet. God is with us when we’re good and when we’re bad, when we’re happy and when we’re sad.

When, finally, the little girl learns about death, she asks her mother if God is present in life or in death. Her mother responds:

My love, God is here with you now, filling your lungs with every breath. God is always near and nothing can separate you — not even death. Because even when you die, God’s arms are stretched out wide, ready to wipe away your tears and greet you on the other side.

The stories we tell about God matter because the stories we tell about God often act as mirrors reflecting back to us the stories we tell about ourselves, our families, our communities and our planet.

The stories we tell about God matter because the stories we tell about God often act as mirrors reflecting back to us the stories we tell about ourselves, our families, our communities and our planet.

When churches tell false stories about the loving God — when churches promote cherry-picked Bible quotes to paint God as an angry, vengeful, emotionally abusive parent — we all lose out. But when we tell stories about a loving God who is always with us and who values and cherishes each of us just as we are, each of us is then able to blossom into all God has brought us into existence to be.

These stories of a loving God are the kinds of stories we humans desperately need both in life and as we approach death.

That point was brought home when Turner shared about two different letters he received in response to his book, When God Made You. The first was from a pastor who also worked as a death doula. She shared that as she went to visit a 99-year-old woman in her last week of life, she noticed Taylor’s book on the side table. Over the last week of her life, the woman asked three different times to have the book read to her. The second letter was from a man who had recently become a father. The infant lived only three hours, and the parents read Turner book to the baby once every hour.

A loving God deserves stories and storytellers that convey God’s love to all. And we — all of us — desperately need those kinds of stories today.

Mara Bim

Mara Richards Bim is serving as a Clemons Fellow with BNG. She is a recent master of divinity degree graduate from Perkins School of Theology at SMU. She also is an award-winning theater practitioner, playwright and director and founder of Cry Havoc Theater Company that operated in Dallas from 2014 to 2023.

Related articles:

Grace and peace to you — at the tip of a sword | Opinion by Mark Wingfield