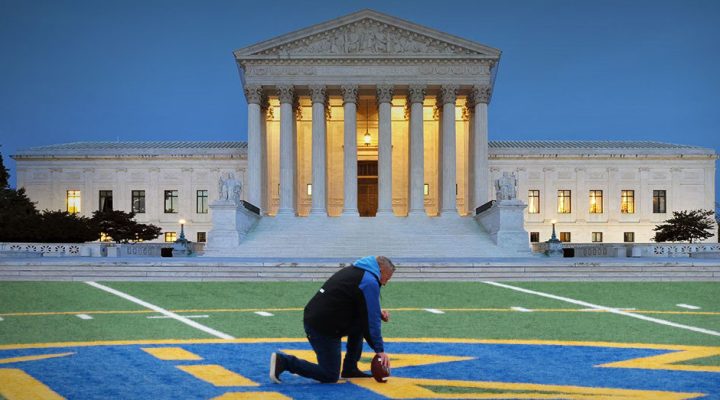

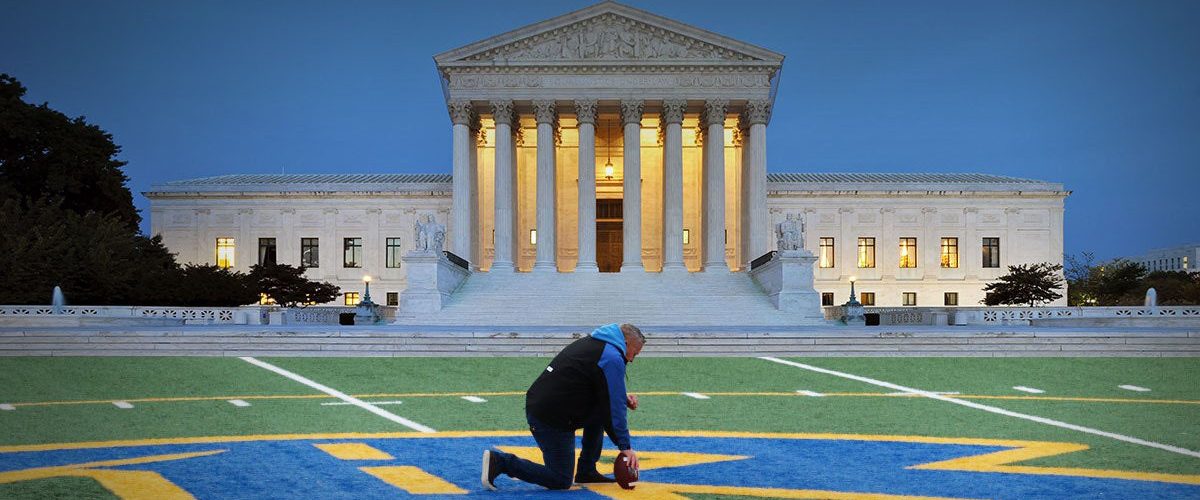

The case of the praying football coach who hasn’t shown up for the part-time job the U.S. Supreme Court ordered restored to him isn’t as simple as a recent BNG news story portrayed it, according to a publicist and an attorney for Coach Joseph Kennedy.

Kennedy was at the center of a notable ruling this summer, when the high court said he should have been allowed to conduct after-game prayers at the 50-yard line as a matter of religious expression.

On Friday, Sept. 23, BNG published an article reporting on a column published in the Seattle Times that said the Bremerton, Wash., school district had complied with the court order and offered to reinstate Kennedy to the role but Kennedy had neither returned the paperwork sent to him nor shown up for work.

In the span of years between when the case was filed and when it was settled, Kennedy moved from the Pacific Northwest to Florida. He’s now on the road giving speeches about how he lost his job for praying in public. He maintains a Facebook page that still lists him as employed as “High School Football Coach at Bremerton High School” from “2008 – Present,” yet he appears to be living in Pensacola, Fla.

On Saturday, Sept 24, BNG received an email first from Jennifer Willingham, Coach Kennedy’s publicist, who is based in Nashville and whose LinkedIn profile states: “I’ve helped launched more than 100 New York Times bestsellers, thousands of bestsellers, live events, and numerous box office hits including four of the most profitable faith films of the last decade.”

Then BNG received an email from Jeremy Dys, senior counsel for First Liberty Institute — the nonprofit law firm representing Kennedy — not disputing any of the specifics of the BNG story but calling it “unfortunate” that BNG did not seek clarification from him and that BNG did not report “that the school district has caused significant delay to this process — and they continue to defy the court.”

BNG and the Seattle Times reported that Kennedy’s legal team stated in court that the coach had been fired from his job when in fact he was suspended with pay and then declined to reapply for the part-time job the next season.

“If your annual review said, ‘Do not rehire’ on it, would you conclude you’ve been invited to stay on, reapply, or were terminated?”

Questioned about this by BNG, Dys responded: “If your annual review said, ‘Do not rehire’ on it, would you conclude you’ve been invited to stay on, reapply, or were terminated? Even if you were to refuse to accept that he was fired, his suspension alone is a sufficient ‘adverse employment action’ based on his religion to attach liability to the district for violating his civil rights.”

The other primary concern stated by both Willingham and Dys is that the school district has repeatedly declined in-person meetings, which they believe are necessary. “One of the main points that should be included in any reporting on the case is that the school district has refused meeting with Kennedy and team three times,” Willingham said.

Attached to Dys’ email were a copy of the latest order from United States District Court for the Western District of Washington and a copy of emails exchanged between Kennedy’s attorneys and the district’s attorneys. That court document does not order an in-person meeting, only “settlement discussions.” And then a footnote adds: “The settlement discussions must involve at least one face-to-face meeting or telephone conference between persons with authority to settle the case. The settlement discussions do not have to involve a third-party neutral at this point.”

BNG does not know what legal documents have been sent between the two parties, nor what is included in the rehiring paperwork the district sent to Kennedy that has not been returned.

Three things are notable about the new information provided to BNG by First Liberty.

First, the Supreme Court ruling sent the original matter back to a lower court to consider details. That lower court, the U.S. District Court based in Seattle, issued a two-page ruling Aug. 26 that outlined two remaining issues in the case: (1) “the form of the injunction and declaratory relief that should issue following summary judgment, including the timing of plaintiff’s reinstatement and the details of the order requiring an accommodation for his exercise of his First Amendment rights” and (2) “the award of plaintiff’s attorneys’ fees and costs.”

First Liberty wants to meet in person; the district’s attorneys believe that’s not necessary.

These two issues are what the attorneys for both sides appear to be debating, with a key disagreement being whether they could meet in person to discuss the solution. First Liberty wants to meet in person; the district’s attorneys believe that’s not necessary.

The district court order states: “The parties shall engage in settlement discussions regarding the remaining outstanding issues. Within 60 days of the date of this order, the parties shall file a stipulation regarding matters on which agreement has been reached and/or a motion for any requested, but opposed, relief. Any motion regarding disputed aspects of the relief or remedy shall be noted for consideration by the court on the fourth Friday after filing.”

That gives the parties until Oct. 25 to reach an agreement — which is three days before Bremerton’s football team is scheduled to play their final game of this season.

On July 11, the executive general counsel for First Liberty wrote to the district’s attorneys to state: “Our client would like to once again raise the desire to meet in-person to resolve all remaining issues in the case.”

That same email outlined three requests from First Liberty on behalf of Kennedy:

- “Immediately reinstate Coach Kennedy to his previous job titles and duties, including as an assistant football coach for the varsity team and as the head coach for the JV.”

- “Promise not to interfere with Coach Kennedy quietly praying by himself for about 30 seconds on the 50-yard line after games (usually immediately after he shakes hands with the opposing coaches).”

- “Pay $5.5 million in fees and costs.”

It has been seven years since Kennedy last worked for the Bremerton district. Most of the players on this year’s high school team were in elementary school when Kennedy last coached there, and the rest of the coaching staff has turned over as well.

It has been seven years since Kennedy last worked for the Bremerton district.

According to lower court records, throughout the fall of 2015, Kennedy tangled with district officials because of his public prayers that were neither silent nor solitary. Even after warnings from district officials, Kennedy publicized his intent to pray after games and was joined on the field by players and others. The district offered other accommodations to his religious expression that would have allowed him to pray out of the spotlight, but he refused those offers.

Thus, what his attorneys now seek from the district — “not to interfere with Coach Kennedy quietly praying by himself for about 30 seconds on the 50-yard line after games” — is something different than the practice that got him suspended in the first place.

According to emails between lawyers provided to BNG by First Liberty, the district has been unwilling to accept the $5.5 million assessment of Kennedy’s legal fees without documentation. As one of the district’s attorneys said on Aug. 8: “Nobody is going to negotiate a $5.5 million request without documentation.”

For now, Kennedy’s attorneys are focused on getting an in-person meeting and the district’s attorneys are focused on getting documentation for the requested $5.5 million in legal fees.

For now, Kennedy’s attorneys are focused on getting an in-person meeting and the district’s attorneys are focused on getting documentation for the requested $5.5 million in legal fees.

First Liberty describes itself as “the largest legal organization in the nation dedicated exclusively to defending religious liberty for all Americans. We believe that every American of any faith — or no faith at all — has a fundamental right to follow their conscience and live according to their beliefs. Our nation’s Founding Fathers established this right as our First Freedom nearly two and a half centuries ago, and we intend to keep it that way.”

The nonprofit organization raises money on its site by promoting cases like Kennedy’s. Its website explains: “You can give with confidence knowing every donation you make to First Liberty Institute is wisely stewarded and invested in the cases and initiatives that will preserve religious liberty today and for the coming generations. And with our network attorneys charging nothing to our clients, since 1997, First Liberty Institute has fought to defend and restore religious liberty in America.”

The website also states: “Throughout our history, we have provided elite legal representation at no charge to our clients. We take pride in providing pro-bono legal assistance to people of all faiths who have been attacked or experienced discrimination due to their religious beliefs.”

Online fundraising appeal for First Liberty Institute

According to the latest IRS filings publicly available, for the year 2019, First Liberty took in $14.4 million in “contributions and grants.” With total income of $14.8 million and expenses of $11.6 million, the entity took in $3.2 million more than it spent in 2020.

Its executive director, Kelly Shackelford, received more than $600,000 in compensation that year — a $130,000 increase over the prior year and a $182,000 increase over a two-year period.

For 2019, the entity reported “attorney fee awards” of $25,716. The year before, the amount of reported “attorney fee awards” was $20,000. The year before that, 2017, it was $202,752. In 2016, the amount was $67,000. In 2015, it was $248,062.

If First Liberty receives $5.5 million in legal fees for the Kennedy case, that would be the equivalent of more than one-third of the agency’s total income ($14,810,000) in 2019.

Related articles:

At the Supreme Court: The First Amendment on the 50-yard line | Opinion by Charles Haynes