Martin Luther King Jr., Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Maya Angelou and Mister Rogers are crowned with halos in the iconography of Kelly Latimore, a Missouri-based artist whose popular works adorn a growing number of homes and sanctuaries.

Depicting these and other inspirational personalities as saints illustrates that manifestations of the divine are not limited to ancient settings, Latimore said. “I am always looking for ways iconography can be used to shed light on the different ways Christ is in plain sight in the world and in all our communities.”

“Good Samaritan,” by Kelly Latimore

In other pieces, Latimore works familiar biblical events and characters into modern dress and settings, such as the Good Samaritan helping a victim of the Flint, Mich., water crisis, Jesus shown as a modern homeless man and Mary, Joseph and infant Jesus depicted as contemporary refugees and asylum seekers.

Latimore said he employs the icon style for these and other renderings because it does more than simply present images of important persons and situations.

“All art can create more dialogue, but icons help us look at God in new ways and help us see each other and our neighbors in new ways. Icons put symbols together in such a way that they are beautiful, and you can easily understand what’s going on.”

As Orthodox Christians have long known, icons also invite viewers into a worshipful relationship with the sacred, he said. “Icons can be venerated and help us see the sacredness in everyone. In their traditional sense, icons can guide us in thought, word and prayer.”

Another quality of iconography is its ability to make viewers contemporary with their subjects, said Robert Black, rector of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Salisbury, N.C. “Looking at them, we are reminded we are not worshiping something that happened way back then. We are participating in something that is continuing to unfold.”

Robert Black

Black’s parish commissioned and installed two 5-by-7-foot Latimore icons, one presenting the Transfiguration of Christ, the other depicting the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. Both were hung on the back wall of the sanctuary and dedicated earlier this year.

Although the works generally follow the Orthodox format for those two biblical events, both also differ in significant ways from most Western-influenced stained-glass portrayals.

In other words, the characters are dark-skinned. “‘The Transfiguration’ lifts up Jesus’ Jewishness. We wanted this to emphasize the Jewishness of Christ and of our faith,” Black said.

The other piece presents people of varying races, genders and ages wearing either contemporary or ancient clothing and gathered around a table as they encounter the Holy Spirit.

“We wanted people to walk in to church to find someone like themselves in that image.”

“We asked Kelly not to feel constrained by traditional depictions of Pentecost,” Black said. “We wanted people to walk in to church to find someone like themselves in that image.”

St. Luke’s reached out to Latimore after conducting a survey of its stained-glass windows after the death of George Floyd and the social unrest that followed, he said. “We were in conversations with African American leaders at that time and realized that if they walked into St. Luke’s and saw our stained glass, they would say, ‘This is a white person’s church.’ At the end of our study, we confirmed that we have a lot of figures that looked like they stepped out of 17th century France.”

Icons commissioned by St. Luke’s

Since the icons were hung on the back wall of the sanctuary, the church has been getting frequent visitors, including out-of-towners, who come to see the works.

“The icons are quite large, and the colors are vibrant and radiant, and they remind me of the wonderful diversity of the body of Christ and the fact that these are living traditions,” Black said.

Latimore, 36, was a part-time landscape and portrait painter living and working in an intentional Christian farming community when he was asked to create an icon representing the spirit of the ministry.

“It was called ‘Christ Considers the Lilies.’ It was a good first try. The lines were a little shaky. Jesus is almost surprised the lilies are in his hands. That was in 2010,” he explained.

But the Ohio community embraced the icon, which became a part of its visual identity. And it wasn’t long before fellow members were asking for personalized icons.

That sparked an awareness of the spiritual power of icons, Latimore said. “Iconography can be a placeholder for a community’s thought, prayer and, most importantly, its action.”

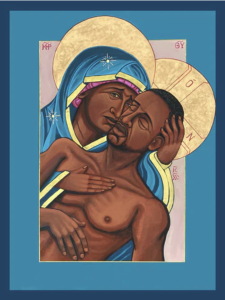

“La Sagrada Familia,” by Kelly Latimore

The 2016 election year also propelled Latimore’s iconography forward. “There was this rise in the country of a lot of anti-stranger, anti-refugee rhetoric, and it was really disturbing to me.”

In response, he painted the image of a modern version of the holy family as refugees fleeing through the desert. “That image — ‘La Sagrada Familia’ — blew everything up,” added Latimore, who said he is mostly involved in the Episcopal Church.

He added that he considers himself to be a painter of icons, rather than one who “prays” or “writes” them in the traditional sense of iconography. “I’ve always thought of it more as painting because that’s what it really feels like.”

Today, Latimore’s iconography ranges from church-commissioned images such as Christ on the throne or Jesus as the Good Shepherd, to social-justice themes that may or may not evoke scriptural scenes or settings.

In “The Good Neighbor,” an African American woman is the Good Samaritan serving clean water to a Black man and victim of toxic water in Flint.

“That one came from a group of pastors involved in the Flint water crisis who were thinking of having me paint an image showing how people in power hurt their neighbors,” the artist explained.

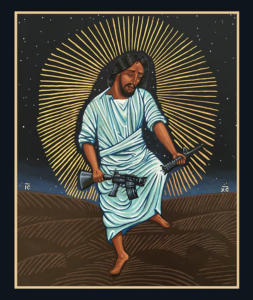

“Jesus Breaks Rifle,” by Kelly Latimore

“Jesus Breaks Rifle” was an answer to several high-profile shootings culminating in the mass killing of Texas school children in May. “After the Uvalde shooting, I thought how sad it is that we are protecting guns over children,” he said.

Icons can show individuals and communities how to respond to tragedy, he added. “There’s this need now in the church for new representations of God and Christ in images that are going to lead us forward and lead to change.”

Depicting Jesus and others in Scripture in darker skin colors is another change Latimore said he is trying to inspire through his iconography. “In America, especially in our sacred art, we have locked Jesus into one image, a white blue-eyed depiction of Jesus. But there is a growing conversation in the church around saints of color and more accurate representations of Jesus as a Middle Eastern man.”

Latimore added that he’s also pushing back against the tradition of what and who is considered a saint and how they are chosen as such.

Kelly Latimore

“For me, in the church for the first 1,000 years it was local congregations and local people who were picking saints and picking the people they knew who had lived lives of love and compassion and caring for the poor and sick.”

“Mama,” by Kelly Latimore

Icons in which the likes of Desmond Tutu, James Baldwin, Flannery O’Connor, John Lewis, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Fannie Lou Hamer are adorned with halos intentionally counter the control religious hierarchies currently have on sainthood, he said. “These people have shown us something about what it means to be Christ in the world. They are physical representations of God’s life in the world. They also show us that miracles are not something up in the clouds but are expressed when someone loved where it hurts and created communion and love in the world.”

And that happens to be the role of icons, Latimore believes.

“My biggest hope for my work is to create a dialogue around sacred art. Is it just glorified wallpaper, or could it be something that galvanizes us toward thought and action? How can we bring more art into our spaces to create more conversation, especially with the harder topics going on in our world?”

Related articles:

Q&A with Daniel Bonnell on conveying the sacred in modern art

Study asks how art influences faith

A pastoral dilemma about art and nudity: embodied faith and raising children in the church | Opinion by Mark Wingfield