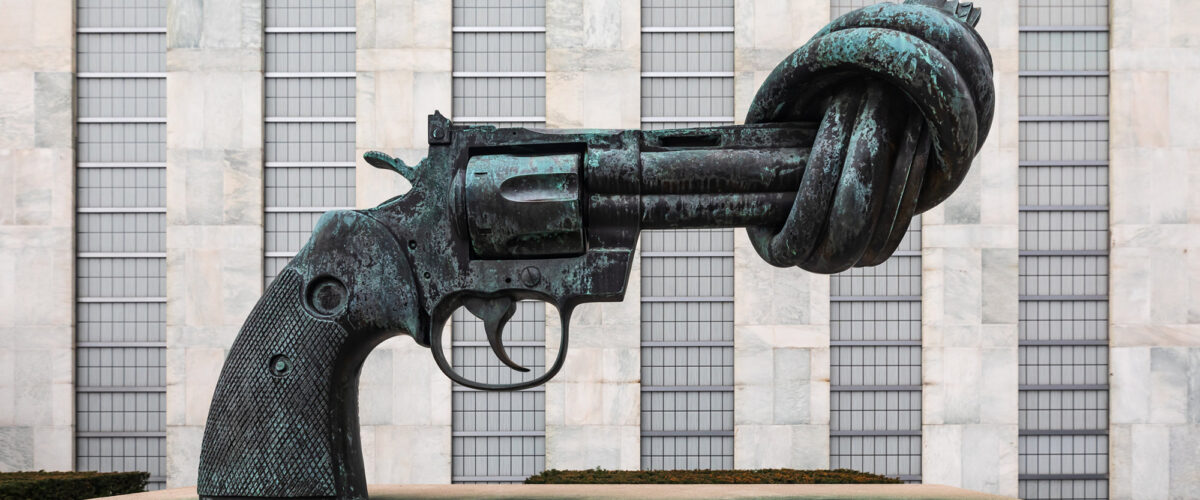

Participants in a May 23-25 virtual conference on Scripture and violence came prepared for discussions on topics such as restorative justice, trauma and biblical interpretation, and criminal justice and the church.

What they weren’t ready for was an elementary school massacre occurring in the middle of the three-day event organized by the Center for the Study of Bible and Violence at Bristol Baptist College in the United Kingdom.

Ashley Hibbard

“The questions of justice and violence are never simple thought experiments or academic issues. These are real people who have suffered real violence, who are going through terrible mourning. That’s at the heart of what we are doing here,” said moderator Ashley Hibbard, lead editor of the Journal for the Study of Bible and Violence.

Panelist Malcolm Foley, director of Black church studies at Baylor University’s Truett Theological Seminary and pastor of discipleship at Mosaic Waco, said the May 24 killing of 19 children and two adults in Uvalde, Texas, was even more painful coming on the heels of the May 15 attack on a Taiwanese Presbyterian church in Southern California and the May 14 Buffalo supermarket shooting in which 10 people were killed.

“It’s extremely difficult and poignant to do a conference on trauma, justice and Scripture when the U.S. is reeling from mass shooting after mass shooting over the course of the last week,” he declared.

“It’s extremely difficult and poignant to do a conference on trauma, justice and Scripture when the U.S. is reeling from mass shooting after mass shooting over the course of the last week.”

The attacks also heighten the stress members of his own intentionally multicultural congregation are experiencing, Foley said.

“I’m in a constant state of thinking about what does it mean to disciple a consistently traumatized people. There are weeks where it’s hit after hit after hit. (Uvalde) is hours away (from Waco) but similar to the mass shooting in Buffalo and the church shooting in California. The fact that you hear about it all the time … keeps you in this constant state of fear. No matter where you are, this kind of violence is unpredictable, so there’s no way to protect yourself from it. The question is, How do you live in the midst of a culture that wants you dead, basically?”

Foley added that pondering such questions has disturbed him greatly. “I have been barely holding it together as I’m daily overcome with rage at the evil of the world.”

Malcolm Foley

The conceptual framework for violence against people of color was the subject of Foley’s presentation. He was joined by fellow panelist Robert Chao Romero, an associate professor in the departments of Chicana/o, Central American and Asian American studies at the University of California at Los Angeles.

Foley focused on the idea of racial capitalism, a concept put forward by Martin Luther King Jr. and subsequently expounded upon by others, Foley said. Dating back to at least the Middle Ages, this is a form of political economy and worldview that rationalizes the exploitation of people for economic gain. “Capitalism, we know, has never not been racial, and racism has always served to undergird it.”

Racial capitalism sets the stage for race-based economic injustice backed up when necessary by various forms of oppression, including violence, he said.

“People don’t like to be exploited, so violence becomes necessary to maintain that exploitation. Consider the purpose of the lash in slavery. Consider the purpose of lynching in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” Foley said. “Consider the use of police violence in impoverished communities. Violence is necessary to maintain exploitation because people don’t like to be exploited.”

Justification is a key part of the cycle of racial capitalism because it enables the perpetrators to oppress without knowing they are doing so, Foley said. “We like to live in ways that tell us we are not exploiting people. So, it’s in everyone’s best interest, seemingly, to construct narratives about ourselves and the systems in which we operate that obscure the ways in which we dominate and exploit one another.”

Participating in such political economies is problematic for Christians, however, because involvement violates Christ’s teachings about justice and the poor, he said.

“For us to amass millions, if not billions, of dollars requires us to sin and requires us to exploit one another. And as Christians that ought not be so. We can’t reduce the size of the camel or increase the size of the needle. We can’t serve both God and mammon. If we are to be justice-minded Christians, we must set ourselves against the evils at hand, and these evils are best understood as domination and exploitation. These are the principalities that press up against us systemically and which we must mobilize against.”

Christianity is a calling to an alternative economic system — the kingdom of God — that centered on Jesus, he added. “Every Christian, if they are worthy of the name, if they are truly united to Christ, if they are truly indwelt by the Holy Spirit, is claiming a commitment to an alternative political economy, a different way of valuing people, a different way of valuing nature, a different way of valuing the world.”

Robert Chao-Romero

Chao Romero said he and others who point out systemic racial injustices are branded as radicals who promote Critical Race Theory. That’s the blowback he’s received after presenting research into the race-based housing policies used to put people of color in “red” zones and whites in “green” zones.

“And when some of us try to come in and say, ‘Hey, wait a minute, look at all this data, look at my life experience, look at my church that’s in the red area.’ When we try to bring that stuff up we get people who say, ‘you’re a Marxist. You’re just CRT. I don’t know what that means but you’re CRT.’”

Chao Romero cited Scripture to explain how he believes God wants humanity to live. “We are called from the vision of Revelation 21, where all the glory and honor of the nations will be brought together. We’re called from the vision of Revelation chapter 7, where people of every nation, tribe, language and tongue will be there together as God’s people. So, John’s vision of beloved community … is the future to which we are called.”

Related articles:

On another classroom full of murdered children | Opinion by David Gushee

Rights, responsibilities and the two-fold commandment of love: A reflection on gun violence in America | Opinion by Greg Garrett

Mass murder and the soundtrack of our lives | Opinion by Justin Cox