Some of the most pernicious and racist political myths circulating in our culture were used as a justification for chattel slavery and later as compelling arguments supporting Jim Crow segregation.

I’ve recently been reading and reflecting on a myth I call “They’re like children,” a false 500-old narrative that Black people can’t be trusted to govern themselves, let alone anyone else, so everyone is better off when white people (particularly white males) are in charge. It’s a myth as old as this nation, but it continues to be used to uphold white male dominance.

Greg Garrett

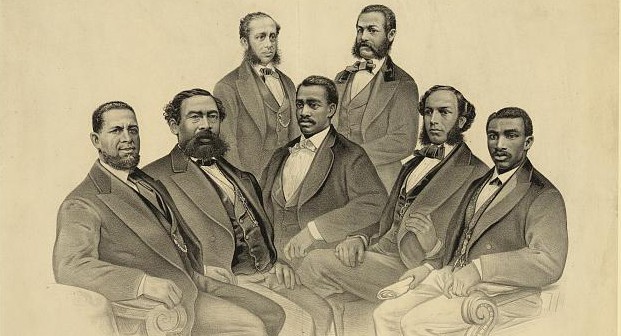

Two images can help us see the disparate versions of this story: one, a Currier and Ives lithograph from 1872, depicts a distinguished group of men in waistcoats and suits. The men are “the first colored senator and representatives — in the 41st and 42nd Congress of the United States,” Robert C. De Large, Jefferson H. Long, H.R. Revels, Benj. S. Turner, Josiah T. Walls, Joseph H. Rainy (Rainey), and R. Brown Elliot. They are a sober and thoughtful-looking group of U.S. Congressmen from Alabama, Florida, Georgia and South Carolina (along with Hiram Revels, a U.S. Senator from Mississippi), all seemingly aware of the monumental responsibility they’ve taken on and steeling themselves for that work.

Sen. Revels understood the twin calls of his election: to represent all his Mississippi constituents and, as the only Black senator, also to speak up for the rights of those now freed from slavery. By all accounts he did this work fairly — he was described as a political moderate — and thoughtfully, and after his term ended, he turned down several political patronage positions to return to his work as an educator to freed slaves and as a minister of the gospel in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Despite his abbreviated service, Sen. Revels was clearly a thoughtful and competent legislator, a shining example of Black leadership.

Scene from “Birth of a Nation”

The second image, a photo identified onscreen in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) as “AN HISTORICAL FACSIMILE of the State House of Representatives of South Carolina as it was in 1870,” is the dark mirror image of that Currier and Ives lithograph. Through the magic of the movies, this empty chamber is suddenly populated by a group of Black legislators who loaf, laugh and drink whiskey on the House floor. Unlike Sen. Revels and his peers, these legislators could not be less dignified, nor can they be trusted to legislate honestly. To the outrage of whites in the gallery, they legislate explicitly to their own benefit, and as Erin Blackmore summarizes the scene, at last “representatives cheer, dance and eat fried chicken as they pass a bill permitting the intermarriage of Blacks and whites.”

The two visions are competing myths. The Currier and Ives print restates the factual truth that there are now and have been in the past competent and accomplished Black leaders. In addition to the five ground-breaking legislators pictured in the lithograph, Robert Smalls was a formerly enslaved person who served five terms in the U. S. House — after stealing a Confederate ship and stealing himself and his family to freedom.

“Every debate about the counting of votes from urban voters leans on the unreliability of people of color.”

My friend Pete Candler of A Deeper South recently posted an image of Rep. Smalls’ gravestone and motto in Beaufort, S.C.: “My race needs no special defense for the past history of them and this country. It proves them to be equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

But the South Carolina legislative scene from D.W. Griffiths’ The Birth of a Nation restates the mythic truth that Black people are not to be trusted to vote or govern, a statement recounted by so many for so long that even today it shapes race relations and politics in America. Every debate about the counting of votes from urban voters leans on the unreliability of people of color; every legislative act limiting how and when Black voters may cast a ballot is a reinstatement of the myth of paternalism.

And in addition to virulent personal racism that holds that whites personally are and must be superior to Blacks, this poisonous myth of paternalism justifies the scaffolding of a multitude of structural and societal setbacks for people of color that are often, then, held up as further evidence of white superiority.

The lithograph of Black legislators represents a moment after the Civil War when Black people momentarily neared the freedoms and responsibilities that America’s founding documents held out to all. It was only a moment: as Henry Louis Gates points out in Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow, caste and racial hierarchy were quickly reimposed on the freed Black population as “white supremacist ideology, which evolved to justify the enslavement of black human beings … continued, unbridled and disengaged from the institution of slavery.”

“Slavery might have ended, but the waters of enslavement simply flowed into a new channel.”

Slavery might have ended, but the waters of enslavement simply flowed into a new channel. As Jim Crow laws began to exclude free Blacks, all of our important forms of discourse — scientific, legal, educational, cultural and, sadly, religious — reengaged the myth that Black people are inferior. The spheres of whites and all others were sharply redefined and returned to the status quo ante: whites (and here I mean, of course, white men) should lead, and act, and vote, and everyone else should just be content to be held in such kind and competent hands.

The present debate about complementarianism and the elevated place of white Christian men in evangelical life illustrates another harmful myth of paternalism, and as both Beth Moore and Russell Moore argued when they exited the Southern Baptist Convention, both forms of control are ungodly attempts to assert that some of God’s children are more important than others of God’s children.

I see and hear these myths echoing, but thankfully, I also hear the countermyths, see the evidence of women, people of color, and women of color excelling, leading and changing the world for the better. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.

And, with God’s help, we can all do everything within our power to see that they get it.

Greg Garrett is an award-winning professor at Baylor University. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of more than two dozen books, most recently In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is currently administering a research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and writing a book on racial mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and Theologian in Residence at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

Barna: Racism a reality even in multiracial churches

Southern Baptists are still obsessed with Critical Race Theory

More churches defined as racially diverse but that doesn’t lead to racial justice work